Deuteronomy 10

The Law and Love

Unknown artists

Christus sitzt im Flüchtlingsboot, 2016, Installation, North Tower Hall, Cologne Cathedral; Photo: © Dr Evan Freeman

Loving the Stranger

Commentary by Evan Freeman

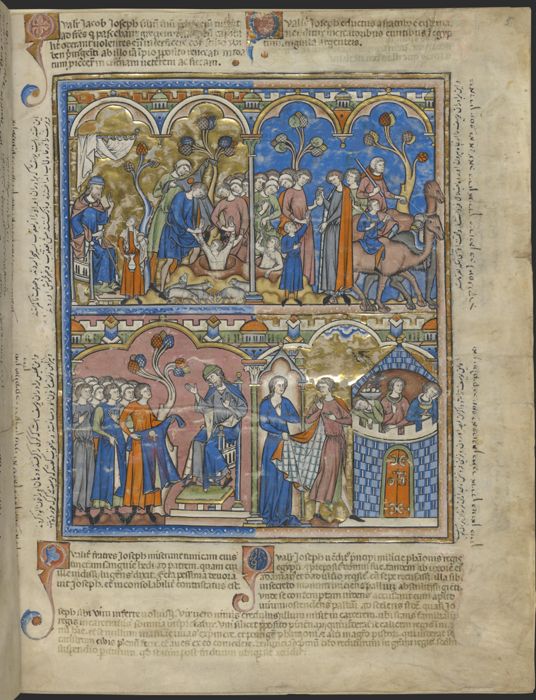

In 2016, a wooden boat was installed inside the main entrance of Cologne Cathedral in Germany. A projector shone a slideshow of photographs of refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea onto the north wall of the church directly above the boat. A second projector shone the installation’s title onto the floor in front of the boat in several languages, beginning with German: Christus sitzt im Flüchtlingsboot; in English: ‘Christ sits in the refugee boat’.

This installation was part of a series of initiatives of the Archbishop of Cologne, Cardinal Rainer Maria Woelki, and his staff. These initiatives blurred the lines between art, performance, and liturgy, and aimed to raise support for refugees. In June 2015, the bells of 230 diocesan churches tolled 23,000 times for the number of refugees who had died in the Mediterranean between 2000 and 2015. In the following spring the archdiocese collaborated with the humanitarian organization Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) to bring a refugee boat from Malta to Cologne. In May 2016, the archbishop celebrated the Corpus Christi Mass on the boat outside the cathedral. During the Mass, the archbishop alluded to the Last Judgement described in Matthew 25 when he preached: ‘Whoever lets people drown in the Mediterranean lets God drown’. It was following this Mass that the boat was installed inside the cathedral’s entrance.

Combining the relic-like wooden boat with projected text and photography, Flüchtlingsboot is unapologetically postmodern in format, and well-suited to a church that boasts both ancient relics and a ‘pixillated’ stained-glass window designed by contemporary artist Gerhard Richter.

Flüchtlingsboot’s location at the western end of the cathedral is significant: images of the Last Judgement frequently adorned the western walls and facades of Byzantine and western medieval churches. Like the cardinal’s words, the Flüchtlingsboot installation evokes Christ’s words in Matthew’s Last Judgement: ‘As you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me’ (Matthew 25:40).

While the title of the installation urges the viewer to look for Christ in the boat, he is nowhere to be found. Instead, churchgoers and tourists are confronted by pictures of contemporary refugees and encouraged to seek God by helping those in need: the strangers in their midst.

In Deuteronomy 10:19, Moses presents just such hospitality to foreigners as a central tenet of God’s Law: ‘You shall also love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt’ (NRSV).

References

2016. ‘Christus sitzt im Flüchtlingsboot, 20 May 2016, www.erzbistum-koeln.de [accessed 13 August 2020]

Unknown artist

Christ handing over the Law to Saint Peter the Apostle (Traditio Legis), 5th–7th century, Mosaic, Mausoleo di Santa Costanza, Rome; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Giving the Law

Commentary by Evan Freeman

This mosaic is located in the circular church of Santa Costanza in Rome. It was once part of a larger cemetery complex that also included the basilica church of Sant’Agnese fuori le mura on the Via Nomentana. Santa Costanza previously contained two porphyry sarcophagi and has historically been identified as an imperial mausoleum for Constantina, daughter of Emperor Constantine I, although this identification is uncertain.

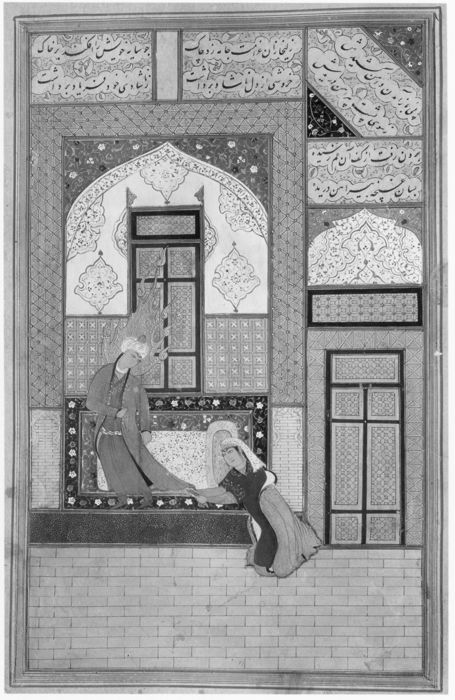

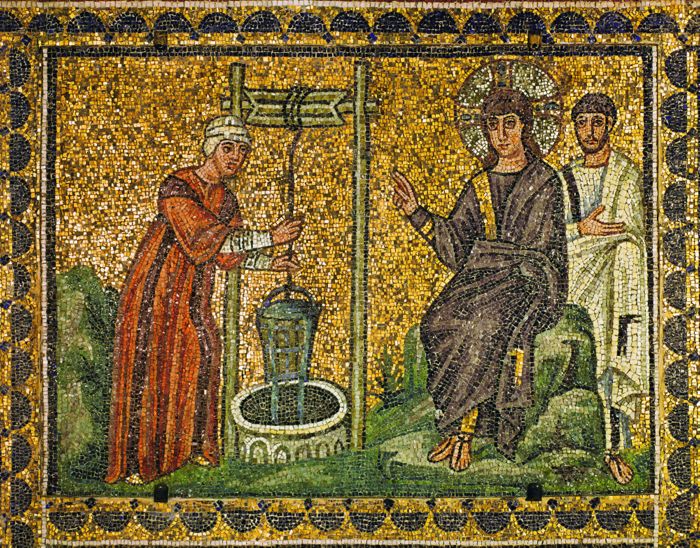

Positioned in the left/southern apse of Santa Costanza, this mosaic is an early example (albeit heavily restored) of the so-called Traditio Legis, or ‘transmission of the Law’, motif. A beardless Christ appears at the centre of the composition, clad in gold, his head haloed with a blue nimbus. Looking out toward the viewer, Christ raises his right hand and holds an unfurled scroll with his left. The text on his scroll—perhaps the result of later restoration—reads DOMINUS PACEM DAT (‘The Lord gives peace’), rather than DOMINUS LEGEM DAT (‘the Lord gives the Law’), which is commonly found in other examples of this motif. Two figures—undoubtedly Saints Peter and Paul—flank Christ on his left and right respectively. The scene recalls Deuteronomy 10, with Christ appearing on the mount as the divine lawgiver and Peter receiving the Law as a new Moses.

This hill, from which three streams issue, probably signifies a paradisal Mount Zion. Originally, there were almost certainly four streams (obscured by later restoration), meant to represent the four rivers of Paradise, which Christian interpreters commonly associated with the four Evangelists and their Gospels. Four sheep reveal Christ to be ‘the Good Shepherd’, a motif that recurs throughout the New Testament.

The paradisal landscape suggests an eschatological setting and may illustrate the Messianic fulfilment of Isaiah 2:2–4, which foretells God’s Law going forth from Zion to all the nations (Bergmeier 2017).

References

Bergmeier, Armin F. 2017. ‘The Traditio Legis in Late Antiquity and Its Afterlives in the Middle Ages’, Gesta, 56.1: 27–52

Holloway, R. Ross. 2004. Constantine and Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press), pp. 93–104

Stanley, David J. 1987. ‘The Apse Mosaics at Santa Costanza: Observations on Restorations and Antique Mosaics’, Mitteilungen des deutschen archäologischen Instituts, Roemische Abteilung, 94: 29–42

———. 1994. ‘New Discoveries at Santa Costanza’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 48: 257–61

———. 2004. ‘Santa Costanza: History, Archaeology, Function, Patronage’, Art medievale, 3.1: 119–40

Unknown artist

Bowl Fragments with Menorah, Shofar, and Torah Ark, 300–50, Glass, gold leaf, 6.9 x 7 x 0.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1918, 18.145.1a, b, www.metmuseum.org

The Holy Ark

Commentary by Evan Freeman

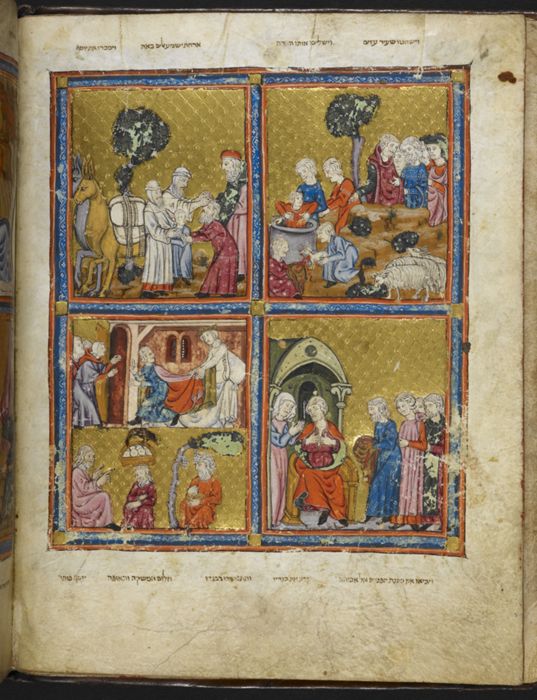

These fragments were once part of a bowl produced by ‘sandwiching’ gold leaf between two layers of glass to display Jewish images and a Latin inscription. The bowl was probably made in Rome between 300 and 350 CE, when artists created numerous gold glass vessels for Jewish, Christian, and pagan patrons, evidencing a common artistic culture shared between these late antique religious communities.

A horizontal line bisects the circular composition on this vessel, creating two registers. Jewish ritual objects appear on top, including a Torah shrine or ‘ark’ at the centre, two menorot (candelabra) on either side, a shofar (ram’s horn), and an etrog (citron). Doors on the Torah ark open to reveal Torah scrolls within. A Torah scroll, or Sefer Torah in Hebrew, typically contains the five books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, although this format was not yet standardized at the time when this vessel was made.

Most of the lower register of this composition has been lost, but part of a fish on a table suggests it once displayed a banqueting scene. A fragmentary Latin inscription exhorts the user to ‘Drink with praise’.

In Deuteronomy 10, Moses recounts how God wrote the Ten Commandments on stone tablets, which Moses then placed in a wooden ark. Following the death of Aaron, the Lord gave the tribe of Levi the task of carrying the ark. In Deuteronomy 31:9, 25–26, we hear how Moses wrote down the Torah and entrusted it to the Levites to be placed in the ark as well.

In late antiquity, the Torah ark and menorah were two of the most prevalent Jewish symbols, appearing on small objects like this vessel and monumental art such as mosaic floors. The ark on this gold glass vessel evokes the Torah shrines found in the synagogues after the destruction of the temple in 70 CE. It is still precious, even in memory.

References

Fine, Steven. 2005. Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World: Toward a New Jewish Archaeology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

———. 2007. ‘Jewish Art and Biblical Exegesis in the Greco-Roman World’, in Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art, ed. by Jeffrey Spier (New Haven: Yale University Press), pp. 25–49

Howells, Daniel Thomas. 2015. A Catalogue of the Late Antique Gold Glass in the British Museum (London: British Museum)

———. 2013. ‘Making Late Antique Gold Glass’, in New Light on Old Glass: Recent Research on Byzantine Mosaics and Glass, ed. by Chris Entwistle and Liz James (London: British Museum), pp. 112–20

Stein, Wendy A. 2016. How to Read Medieval Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Unknown artists :

Christus sitzt im Flüchtlingsboot, 2016 , Installation

Unknown artist :

Christ handing over the Law to Saint Peter the Apostle (Traditio Legis), 5th–7th century , Mosaic

Unknown artist :

Bowl Fragments with Menorah, Shofar, and Torah Ark, 300–50 , Glass, gold leaf

Receiving the Law, Yesterday and Today

Comparative commentary by Evan Freeman

The book of Deuteronomy contains three speeches delivered by Moses to the people of Israel on the plains of Moab as they were about to enter the Promised Land. In Deuteronomy 5, Moses recounts the Ten Commandments. The first half of Deuteronomy 10 describes Israel’s reception of the Law. Moses recalls placing the two stone tablets inside an ark made of acacia wood. Other biblical texts record that the ark was placed within the Tabernacle (Exodus 40), and later, in Solomon’s temple (1 Kings 8; 2 Chronicles 5).

The gold glass bowl fragments now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York testify to the enduring importance of the divine Law for the Jewish people. Following the Roman siege of Jerusalem and subsequent destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, the synagogue and its trappings became increasingly central to Jewish religious practice. From as early as the third century, Jewish texts and images began associating synagogue Torah shrines with the ark of the covenant, even referring to the Torah shrine as an ‘ark’ in Hebrew. This process illustrates what Steven Fine has termed the ‘templization’ of the synagogue during this period (Fine 1997: 55–59). To this day, the holy ark, or aron kodesh, is usually oriented toward Jerusalem and is a focal point in most synagogues.

The Hebrew Bible and its Law are likewise of great importance for Christianity and Islam, the two other major ‘Abrahamic’ faiths. The New Testament presents Jesus as the Word (Logos) and Wisdom (Sophia) of God. According to the Gospels, Jesus and his disciples provoked the ire of contemporary religious authorities for seeming to flout the Law, for example, by healing and picking grain on the Sabbath. Yet in other instances, such as the Sermon on the Mount of Matthew 5, Jesus affirms and even seems to raise the bar for many of the commandments passed down from Moses, by calling his followers to turn the other cheek (Matthew 5:39), to love their enemies (Matthew 5:44), and so on.

In Matthew 5:17, Jesus explains that he has come ‘not to abolish but to fulfil’ the Law and the prophets. John’s prologue summarizes the Christian understanding of Moses and Christ as two pillars of the old and new covenants: ‘For the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ’ (John 1:17). Because of the close association between Christ and the Law, many Christian commentators interpreted the ark—a container for the Law—as an image of the Virgin Mary who bore Christ.

The traditio legis motif, seen in the mosaic at Santa Costanza, exemplifies this Christian understanding of Christ as the messianic fulfillment and embodiment of God’s Law. Christ appears amidst clouds above a mount from which the four rivers of paradise flow. His exalted position recalls his activity throughout salvation history as the Word and Wisdom of God, while at the same time anticipating his eschatological return. The four rivers, symbols of the Gospels, stress the central importance of Christ’s teaching. Historically, a book of the Gospels was placed on Christian altars, and readings from the Gospels have long enjoyed prominence in Christian church services.

The beleaguered state of the Santa Costanza mosaic, much restored through the centuries, presents considerable difficulties for scholarly interpreters seeking to reconstruct its original appearance. But such a ‘living’ artwork—to which artists have repeatedly returned to preserve and rework the original image—exemplifies the hermeneutical task of faith communities seeking to interpret and apply ancient sacred texts in the present.

In the second half of Deuteronomy 10, Moses delivers a powerful exhortation. The Lord has chosen and multiplied the people of Israel and will continue to love their ancestors. But what does the Lord require of Israel? Moses reminds Israel to fear, follow, love, and worship God alone, and to keep his commandments. Because God cares for orphans, widows, and strangers, Moses calls on Israel also to love the stranger in their midst.

In a time of widespread racism and xenophobia, the Christus sitzt im Flüchtlingsboot installation in Cologne Cathedral presents a compelling example of a contemporary faith community seeking to respond to the European migrant crisis and uphold the biblical mandate to show hospitality to foreigners. While contemporary people may often strain to find relevance in many of the ancient commandments that seem culturally contingent, the commandment to show hospitality to the stranger in Deuteronomy 10 remains as relevant today as ever.

References

Fine, Steven. 1997. This Holy Place: On the Sanctity of the Synagogue During the Greco-Roman Period (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press)

Commentaries by Evan Freeman