Obadiah 1:1–9

Pride Comes before a Fall

David Bomberg

"Hear, O Israel", 1955, Oil on panel, 91.4 x 71.1 cm, The Jewish Museum, New York; Purchase: Oscar and Regina Gruss Charitable Foundation Fund, 1995-33, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / DACS, London John Parnell / The Jewish Museum, New York / Art Resource, NY

Divine Comfort Amidst Despair

Commentary by David Emanuel

With predominantly thick and vertical brush strokes, the English painter David Bomberg created an indistinct image of a shrouded man clasping his hands, with a Torah scroll tucked between his right arm and body. The figure—whom many believe to be Bomberg himself—appears to be looking downwards, perhaps immersed in some personal grief. This sadness may reflect the artist’s disillusionment towards the end of his career, as he found his work critically dismissed or ignored.

The painting’s title, Hear, O Israel, captures the opening words of the Shema, ‘Hear O Israel the Lord our God the Lord is one’, (Deuteronomy 6:4) which is recited daily by devout Jews. The colours employed by the artist—predominantly light browns, beige, and rustic reds—bring to mind those of the Judaean desert in Israel, landscapes with which the painter was familiar (Cork 2003).

Like Bomberg’s painted figure, Obadiah’s life and ministry are indistinct. Even the meaning of the name Obadiah remains disputed. Depending on the Hebrew vowel pointing, it could either mean ‘worshipper of the Lord’ or ‘servant of the Lord’. Although Rabbinic literature (Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 39b) connects him to the prophet ministering during the days of Elijah (1 Kings 18:3), contemporary scholarship leans towards a ministry during or soon after the Babylonian exile in 586 BCE (Longman and Dillard 2006: 436).

The grief and introspection that may be discerned in Bomberg’s possible self-portrait help to evoke the deep-seated despair experienced by Obadiah in exile. The prophet’s land lay desolate and his people had been exiled to Babylon. In this grief, Obadiah’s only hope, the thing to which he would have clung, was the word of God. Obadiah would have been familiar with the words of Torah together with words we also find in Jeremiah, which parallel Obadiah’s prophecy (cf. Jeremiah 49:9–10, 14–16; Obadiah 1–6) and foretell judgement against Edom, who joined with the Babylonians in their sacking of Jerusalem and Judea (cf. Psalm 137:7; Ezekiel 25:12). For both Bomberg’s subject and for Obadiah, the nearness of God’s word (as suggested in the painting by the scroll) may have generated a sense of divine comfort, even amidst despair.

References

Barton, John. 2001. Joel and Obadiah: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press), pp. 120–123

Cork, R. 2003. ‘Bomberg, David’. Grove Art Online. http:////www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000009782 [accessed 14 Oct. 2018]

Longman III, Tremper, and Raymond B. Dillard. 2006. An Introduction to the Old Testament, 2nd edition (Grand Rapids: Zondervan)

Niehaus, Jeffrey J. 2009. ‘Obadiah’, in The Minor Prophets: An Exegetical and Expository Commentary, ed. by Thomas Edward McComiskey (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic), pp. 496–502

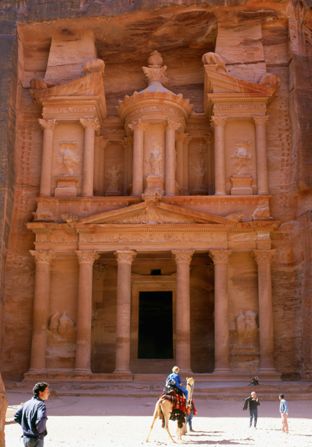

Unknown Nabataean artist

Al Khazneh (The Treasury), 1st century CE, Architecture, Petra, Jordan; Pictures from History / David Henley / Bridgeman Images

Edom’s Lofty Dwellings

Commentary by David Emanuel

Tucked away in the mountains of eastern Jordan lie the remains of the ancient city of Petra, in the territory of biblical Edom. The name Edom, which means ‘red’ in Hebrew, reflects the hue of the sandstone from which the city was constructed. Perhaps the most impressive surviving feature of the ruins is the towering Al Khazneh or ‘Treasury’, a carved edifice that stands over thirty metres tall. Although the structure is commonly referred to as the Treasury, it is believed originally to have served as the mausoleum of the Nabataean King Aretas IV in the first century CE.

When addressing the Edomites, Obadiah refers to them as, ‘You who live in the clefts of the rock, whose dwelling is high’ (v.3). At the time of Obadiah’s prophecy, the Edomites had built their settlements in the region of Petra, creating for themselves an elevated dwelling that was naturally easy to defend. The wording of Obadiah 3, ‘in the clefts of the rock’, additionally suggests the Edomites, like the Nabataeans after them, carved out their accommodations from the sandstone and used natural caves to create secure living spaces. So although Al Khazneh was constructed approximately 500 years after Obadiah prophesied, it remains a stunning visual representation of Edom’s dwelling places, bringing Obadiah’s words vividly to life.

It appears that the location’s perceived defences engendered a false sense of security among the inhabitants of Edom, to the point that they felt untouchable. Obadiah’s words in verse 3 expose this sentiment. He addresses the Edomites as ‘You … who say in your heart, “who will bring me down to the ground?”’.

Despite the ostensible security of their dwellings and the pride of their hearts, Obadiah’s words to ancient Edom proclaimed destruction against them; even though they were lodged in high mountain fortresses, the God of Israel would bring them down, ‘Though your nest is set among the stars, thence I will bring you down’ (v.4).

References

Bienkowski, Piotr. (ed.). 1991. The Art of Jordan: Treasures from an Ancient Land (Stroud: Alan Sutton)

Wright, G. R. H. 1997. ‘The Khazne at Petra: Its Nature in the Light of its Name’, Syria: revue d’art oriental et d’archéologie, 74.1: 115–20

Pierre-Paul Prud'hon

Justice and Divine Vengeance Pursuing Crime, 1808, Oil on canvas, 244 x 294 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris; 7340, Scala / Art Resource, NY

Measure for Measure

Commentary by David Emanuel

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon’s Justice and Divine Vengeance Pursuing Crime masterfully captures a crime scene.

Standing out at the bottom of the painting is the victim of a brutal robbery, with blood still seeping from a wound in his chest. To the left we see the perpetrator (Crime) fleeing the scene with the victim’s belongings in his arms. With his gaze on the corpse, Crime remains oblivious to the figure of Divine Vengeance above, who has sought him out. The personification of Vengeance is depicted looking back at another personification (of Justice), who carries a sword in her right hand poised and ready to strike the night robber.

Prud’hon’s depiction of Crime, who comes at night to perform his wicked deeds, illuminates two aspects of Obadiah’s prophecy: Edom’s crimes against Judah, and God’s punishment of Edom. When the Babylonians sacked and exiled Judah in 586 BCE, Edom was at their side pillaging and reoccupying the deserted Judaean villages, acting like thieves in the night, lying concealed under cover of the Babylonian army. Like to Prud’hon’s thief, Edom attacked and pillaged a helpless victim, believing it could escape punishment. The other aspect of Obadiah’s prophecy concerns God’s punishment of Edom. Here, Obadiah employs the image of the thief in the night: verse 5 says, ‘If thieves came to you, if plunderers by night—how you have been destroyed!’.

Together, these two perspectives highlight the ancient concept of lex talionis. Present in the New Testament (see Matthew 7:2) and Rabbinic literature (Mishnah Sotah 1:7), this is the principle of measure for measure: with the same measure a sin or crime is committed, the perpetrator is punished. Edom acted as a thief in the night, plundering its neighbours, and as equal recompense, it too would be plundered, as indicated in Obadiah 6: ‘How Esau has been pillaged’.

References

Hill, Andrew E., and John H. Walton. 2009. A Survey of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House)

Weston, Helen. 1975. ‘Prud’hon: Justice and Vengeance’, The Burlington Magazine, 117.867: 353–363

David Bomberg :

"Hear, O Israel", 1955 , Oil on panel

Unknown Nabataean artist :

Al Khazneh (The Treasury), 1st century CE , Architecture

Pierre-Paul Prud'hon :

Justice and Divine Vengeance Pursuing Crime, 1808 , Oil on canvas

The Day of the LORD’s Reckoning

Comparative commentary by David Emanuel

At various points in the history of Israel, God’s prophets declare a time in the future when he will judge his people or the nations surrounding Israel. The prophet Isaiah captures this notion well, ‘For the Lord of hosts has a day, against all that is proud and lofty, against all that is lifted up and high’ (Isaiah 2:12). The first nine verses of Obadiah—together with the artworks in this ‘exhibition’—may be read as reflecting three aspects of this divine judgement: the object against which it is unleashed, its inevitability, and the aftermath of its unleashing.

Petra’s Treasury, as this construction is most commonly known, can be read as an inflated proclamation of self-worth. The extravagant features of the façade accentuate the structure’s claims to royal splendour and grandeur. Designed at least in part by Greek architects, its Corinthian columns are fine and intricate in their details, and there are eagles of Zeus perched atop each side of the broken pediment. If we understand pride as a hubristic sense of importance, then the Treasury exemplifies the idea. This same sense of pride echoed amongst those who dwelt in this region 600 years before the structure was carved: the sons of Edom, the object of God’s judgement. It was Edom’s pride that ultimately led to their destruction, as Obadiah states, ‘The pride of your heart has deceived you’ (v.3). For all of its captivating external magnificence, this royal tomb was still in the end a tomb: a place where the bones of the dead were housed.

Although God’s judgement may at times seem slow in coming, Obadiah is sure that eventually it will arrive; Pierre-Paul Prud’hon’s work generates this sense of determined inevitability. He captures an instance in which a brutal murder and robbery have taken place, as the perpetrator begins his escape. The portrayal of the robber’s garments flowing behind him draws attention to the speed of his flight. Although the perpetrator works under cover of darkness and looks around for anyone who may have witnessed the crime, his attempts to conceal his actions are futile. Justice and Divine Vengeance have located and overtaken him, and he will inevitably be brought low. As the painting makes evident, there can be no escape.

The prophesied destruction of Edom was not instantaneous, and we know that Edom still occupied Judaean villages during the early Persian period (c.538 BCE). In 1 Esdras 4:50, Darius, at the request of Zerubbabel, ordered the Edomites to return the villages of the Jews that they held. However, we also know that by 450 BCE, God’s judgement had been executed. The prophet Malachi (who prophesied between 475–450 BCE) writes concerning Edom: ‘I have laid waste his hill country and left his heritage to jackals of the desert’ (Malachi 1:3). Though it may not have come in the days of Obadiah, God’s judgement was executed against the proud.

David Bomberg’s Hear, O Israel presents a stark contrast to the photograph of the ‘Treasury’. Instead of pride and arrogance, the near-abstract subject of Bomberg’s painting presents an image of humility. There is nothing glamorous or flamboyant about this man; nothing that screams of great material wealth and riches. His clothes appear simple, and even the Torah scroll in his arms lacks any visible ornamentation. If it is a self-portrait, the blurred figure suggests a desire on the part of the artist to appear obliquely rather than to display himself proudly. Likewise, the subject’s head seems to be inclined downwards rather than being held high.

The painting opens a pathway to an interpretation of the prophet Obadiah, and the nation of Israel at the time the prophet penned his oracle. The people of Judea had once demonstrated pride in the perceived security and position they held before God, expressing confidence that they would never be moved (see Jeremiah 7:2–4). But after 586 BCE, even though they were his people, they experienced the judgement of God via the Babylonian army.

Obadiah was well aware of the inescapable nature of God’s judgement since he and his people had been humbled for their pride and arrogance. This in itself would have created a sense of comfort, knowing that the words of his prophetic utterance against Edom—judging them for their brutality towards Judah—would eventually be fulfilled.

References

Longman III, Tremper, and Raymond B. Dillard. 2006. An Introduction to the Old Testament, 2nd edition (Grand Rapids: Zondervan), p. 498

Commentaries by David Emanuel