Isaiah 60

And Kings Shall Come

Works of art by Edward Burne-Jones, Vasco Fernandes and Unknown Neapolitan artist, follower of Giotto

Vasco Fernandes

Adoration of the Magi (Panel from the altarpiece of the chancel of Viseu Cathedral), 1501–06, Oil on oak panel, 131 x 81 cm, Grâo Vasco Nacional Museum, Viseu, Portugal; ©️ Photo Josse / Bridgeman Images

An Amerindian King

Commentary by Jonathan K. Nelson

For the first time in Europe, this painting represents one of the ‘Three Kings’ (i.e., one of the Magi referred to in Matthew 2) as an Amerindian.

The Adoration of the Kings constitutes one of eighteen panels painted between 1502 and 1506 by Vasco Fernandes and Francisco Henriques for the high altarpiece of Viseu Cathedral, in central Portugal. Only in 1500 had Europeans landed in modern-day Brazil, with a Portuguese fleet led by Pedro Alvares Cabral. His ancestors were buried in the Viseu Cathedral, which helps explain the local interest in the New World inhabitants. The first letters about the Tupinambá described their feathered headdresses and weapons (ibirapema), comparable to those of the central king in the Adoration, though his exotic jewellery and European clothing are fanciful (Chicagana-Bayona 2004: 107).

Crucially, given that the artists had not seen Amerindians in person, the texts specified that they were ‘brown’ and ‘innocent’. The dark-skinned king bears a black ceramic (?) container containing grains, surely frankincense, which allowed viewers to identify it with the incense in the prophecy in the book of Isaiah (60:6). Mary hands Joseph the golden vessel of the kneeling eldest king, who has presented a gold coin to the Christ child. This unusual detail is held up to show an armillary sphere, the personal and royal device of King Manuel of Portugal. The container carried by the youngest king, at left, must hold myrrh.

Like the rest of the altarpiece, the Adoration is based on Flemish paintings, but those prototypes typically showed one king as Black. The colouration reflects the belief, derived in part from Isaiah, that one of the Three Kings came from Sheba (v.6), typically identified with Africa or India.

In 1495, Columbus, however, had announced that Sheba was Cuba (Trexler 1997: 137). Perhaps some Portuguese also placed it in the New World, which was then often confused with India. Certainly, the painting indicates that Amerindians were seen as future Christians under the rule of Portuguese kings.

References

Chicagana-Bayona, Yobenj Aucardo. 2004. ‘Imago Gentilis Brasilis. Modelos de Representação Pictórica do índio da Renascença’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, Universidade Federal Fluminense)

Koerner, Joseph. 2010. ‘The Epiphany of the Black Magus circa 1500’, in The Image of the Black in Western Art: From the ‘Age of Discovery’ to the Age of Abolition. Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque (vol. 3, part 1), ed. by David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

Trexler, Richard. 1997. The Journey of the Magi: Meanings in the History of a Christian Story (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Edward Burne-Jones

The Annunciation and the Adoration of the Magi, 1861, Oil paint on 3 canvases, 108.6 x 73.7 cm; 108.6 x 156.2 cm; 108.6 x 73.7 cm, Tate; Presented by G.H. Bodley in memory of George Frederick Bodley 1934, N04743, ©️ Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

English Pilgrims

Commentary by Jonathan K. Nelson

Like other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Edward Burne-Jones found inspiration in Renaissance paintings. But this Adoration of the Kings, one of his first major works, also reveals how he reinterpreted sacred stories in those works to revitalize ecclesiastical decoration.

Commissioned for St Paul’s in Brighton, UK, the altarpiece has the traditional triptych format commonly found in Medieval and Renaissance altarpieces; here, the side panels depict the Annunciation. Burne-Jones described the work as ‘an old Venetian picture’, and his representation of the central ‘king’ as a bearded and turbaned Black man might reflect Paolo Veronese’s Adoration of the Kings (1582) in Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice.

From Italian examples, Burne-Jones could have found inspiration for the inclusion of portraits. The first king borrows facial features from the artist William Morris, whose wife Jane appears as Mary. Burne-Jones represented himself in the corner and the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne playing bagpipes, in the guise of the two shepherds at the upper right. These members of the painter’s inner circle probably indicate his personal engagement with the subject.

From his theological studies at Oxford, Burne-Jones knew that the three Magi who adored the Christ child were often associated with a passage in Isaiah 60:3 ‘Nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn’. In his altarpiece, people from the distant lands of Africa and England pay homage to the Messiah, whose divine light is indicated by the star and glowing background.

In his discussion of a later Adoration by Burne-Jones, published in the aptly named Sermons in Art (1908), the Reverend James Burns interpreted the Magi’s journey as ‘the Soul’s Quest for God’, reminiscent of the Quest for the Holy Grail (Crossman 2007: 420). This offers a possible explanation for Burne-Jones’s unusual decision to represent one Magus as a knight. Perhaps the artist also agreed with Burns that the Magi were ‘pilgrims of the Spiritual Way’.

In this ‘sermon in art’, Burne-Jones depicted himself as a modern English pilgrim, searching for new ways to express his spirituality.

References

Crossman, Colette. 2007. ‘Art as Lived Religion: Edward Burne-Jones as Painter, Priest, Pilgrim, and Monk’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Maryland)

Scott, Rachel, et al. 2021–22. ‘The Making of a Triptych: The Annunciation and Adoration of the Magi 1861 by Edward Burne-Jones’, Tate Papers 34, available at https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/34/the-making-of-a-triptych-the-annunciation-and-adoration-of-the-magi-1861-by-edward-burne-jones [accessed 26 July 2022]

Wildman, Stephen and John Christian. 1998. Edward Burne-Jones, Victorian Artist-Dreamer (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

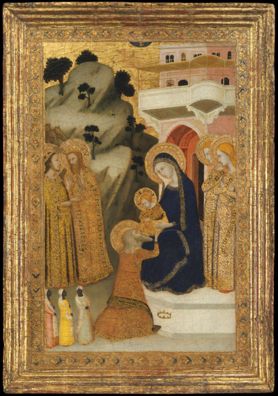

Unknown Neapolitan artist, follower of Giotto

The Adoration of the Magi, c.1340–43, Tempera on wood, gold ground, 66.4 x 46.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Robert Lehman Collection, 1975, 1975.1.9, www.metmuseum.org

African Ambassadors

Commentary by Jonathan K. Nelson

Who are the three Black figures in this Adoration of the Kings, painted in the 1340s?

The Black men must hold a special significance for this anonymous artist who worked in Naples. They are the only non-Western figures in the painting or in its two known companion pieces depicting the Annunciation and Nativity (now in the Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence). Those panels once bore the symbols of the Anjou and Aragon families, probably indicating that the altarpiece was commissioned by or for the family of Robert of Anjou, King of Naples.

Royal riches abound in the Adoration, as seen in the elaborate palace and garments of Christ, the king of kings. Extremely ornate clothing, with an abundance of gold, also adorns the eldest king kneeling in the centre, his two younger companions on the left, and the angels on the right.

Isaiah 60:5 was a key source for the widespread Christian belief that the Magi mentioned by Matthew 2 were kings who came from afar.

The artist evokes the ‘wealth of the nations’ brought as tribute from these visiting ‘kings’. The prophet then referred to camels coming from Midian, Ephah, and Sheba. Perhaps this passage inspired an artist who had never seen camels to create the three unusual-looking animals visible behind the standing kings.

The absence of halos indicates that these individuals, like the comparable ones in the Nativity, are not holy figures. Neither kings nor attendants, the Black men probably reflect the group of Christian Africans who in the early 1300s travelled to Avignon, and then Rome, to pay homage to the Pope (Kaplan 1985: 12). An account written before 1330 described this remarkable event and identified the visitors as ambassadors from the ‘emperor of the Christian Ethiopians’ (Bausi and Chiesa 2019: 28). Many Europeans believed the ruler had descended from one of the three Kings. The ‘ambassadors’, most probably pilgrims, provided living proof of Christian communities beyond Europe.

Perhaps the artist even saw the Africans in person, given the unusually accurate representation of their physiognomy and clothing. He then transformed an ephemeral event into a timeless image to indicate the global reach of Christianity.

References

Bausi, Alessandro and Paolo Chiesa. 2019. ‘The Ystoria Ethiopie in the Cronica Universalis of Galvaneus de La Flamma (d. c.1345)’, Aethiopica 22: 1–51

Kaplan, Paul H. D. 1985. The Rise of the Black Magus in Western Art (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press)

Powell, Mark Allan. 2000. ‘The Magi as Kings: An Adventure in Reader-Response Criticism’, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 62: 459–80

Vasco Fernandes :

Adoration of the Magi (Panel from the altarpiece of the chancel of Viseu Cathedral), 1501–06 , Oil on oak panel

Edward Burne-Jones :

The Annunciation and the Adoration of the Magi, 1861 , Oil paint on 3 canvases

Unknown Neapolitan artist, follower of Giotto :

The Adoration of the Magi, c.1340–43 , Tempera on wood, gold ground

A Spirituality of Many Races

Comparative commentary by Jonathan K. Nelson

The short passage in Matthew (2:1–12) about the Magi who travelled from the East to find the Christ child provided few details for artists who needed to depict this scene and for theologians who tried to understand it. Some turned to earlier texts, especially Isaiah 60:1–6, which seemed to provide not only a prefiguration of the birth of the Messiah but also precious information about the status and origins of the wise men.

Matthew’s reference to the Magian gifts of ‘gold, frankincense, and myrrh’ established the convention, at least in the Western Church, that the Wise Men numbered three. Most importantly, this passage allowed for the identification of this trio with the kings who, as envisioned by Isaiah, ‘shall come […] to the brightness of your rising’, and ‘shall bring gold and frankincense’ (Isaiah 60:3, 6). Though the Bible never suggests that these Magi or Wise Men were royal, they were presented as models for kings by St Augustine (354–430 CE) and identified as kings by Caesarius of Arles (468/470–542 CE) and other Early Christian sources (Powell 2000). Paintings like those in this exhibition (and countless others) helped reinforce this regal association.

Isaiah’s account introduced a triumphant tone to the biblical narrative and invited readers since Christ’s birth to imagine worldly rulers coming to pay homage to the infant who is also king of kings. Meanwhile, ancient Roman reliefs depicting imperial triumphs provided a model for Western artists as they created a new iconography for this scene. Isaiah’s text encouraged painters to represent royal visitors in all their glittering riches, thus providing insight into the ideal presentations of kingly attire and comportment.

In all three paintings in this exhibition, the king closest to Christ appears kneeling after removing his crown, to show his submission to a more powerful leader. Typically, as seen in the two examples from the 1300s and 1500s, this king is also the oldest, indicated by his white beard, and has already presented his gift.

Isaiah’s reference to the dawn, combined with Matthew’s discussion of the star, and the theme of joyful homage, is suggested by the glowing backgrounds found in so many Adoration paintings, including those by Edward Burne-Jones and the anonymous Italian artist. Very often, as in this last-mentioned work, representations of the Adoration of the Kings also depict camels, a detail mentioned not in the Gospels but Isaiah 60:6. Importantly, the prophet specified that the camels came from Midian, Ephah, and Sheba, and the sheep and rams from Kedar and Nebaioth. In a highly influential commentary on this passage from the fourth century, Eusebius of Caesarea (c.260/265–339 CE) explained that Isaiah thus ‘alluded to the nations of other races and tribes’ (Commentary on Isaiah, 60.6–7).

Similar interpretations led to the pervasive belief in medieval and early modern Europe that the Three Kings came from different geographic areas; one of them was often described and represented as Black. In part, this is because Sheba was traditionally associated with Africa, though especially before the Age of Exploration, the name and location of this area was often confused with India. Many Europeans in the early 1500s identified the Americas with India, and some placed Sheba in the New World; this might explain why a handful of paintings made in Europe and South America, including our example in Portugal, shows one king as an Amerindian.

Representations of Black kings and attendants appear in countless Renaissance paintings, especially after 1450. These royal Africans, but also the Black visitors in the Italian work shown here, probably reflect that widespread conviction that Ethiopia was ruled by a rich and powerful king named Prester John. This Christian ruler, thought to be a descendant of the Black Magus, was sought by Popes as a key ally in their fight against Muslims, and thus had a massive impact on European understandings of Ethiopians.

In his commentary on Isaiah, Theodoret of Cyrus (c.393–c.458/466 CE) wrote that the Church ‘gathers its children from all the nations’ and is ‘seized with amazement in contemplating the clouds of people who hasten towards it’ (Commentary on Isaiah, 19.60.4–8). The paintings in this exhibition, with their depictions of children from so many nations, convey and stimulate a similar amazement. Like Isaiah’s text, they invite viewers to reflect on the spiritual devotions of peoples all around the world.

References

Elowsky, Joel C. (ed.), Armstrong, Jonathan J. (trans.). 2013. Eusebius of Caesarea: Commentary on Isaiah, Ancient Christian Texts (Downers Grove: IVP), pp. 293–94

Elliott, Mark W. (ed.). 2007. Isaiah 40–66, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, Old Testament 11 (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press), p. 230

Kaplan, Paul H. D. 1985. The Rise of the Black Magus in Western Art (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press)

Sawyer, John F. A. 2017. Isaiah Through the Centuries (Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell)

Trexler, Richard. 1997. The Journey of the Magi: Meanings in the History of a Christian Story (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Commentaries by Jonathan K. Nelson