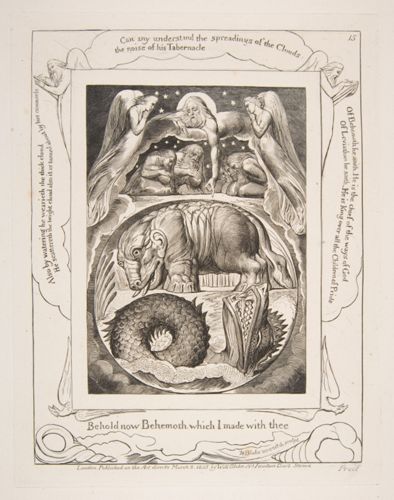

Job 40–41

Behemoth and Leviathan

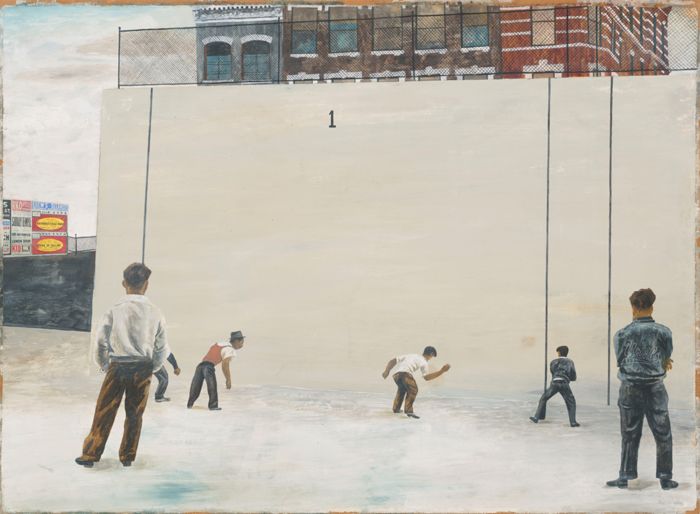

William Blake

Behemoth and Leviathan, from Illustrations of the Book of Job, 1825–26, Engraving, 411 x 275 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Edward Bement 1917, 17.17.1–15, www.metmuseum.org

‘Behold now Behemoth, which I Made with Thee’

Commentary by Gerald West

William Blake was haunted by the book of Job, returning to this biblical text again and again.

What is surprising in Blake’s depiction of Behemoth and Leviathan in both his watercolours and engraving of the subject is how constrained these creatures are, encapsulated in a circle, the womb of God’s creation. Earlier, in 1794, Blake’s well-known poem ‘The Tyger’ asks a Job-like question of God concerning creatures like Behemoth and Leviathan: ‘Did he who made the Lamb make thee?’ But in Blake’s reflections on the book of Job the only questions are God’s.

In the watercolours and engraving both Behemoth and Leviathan are contained, clearly within and under God’s control, though Leviathan in particular conveys a sense of impending movement and power. God, angelic creatures, Job, Job’s wife, and Job’s three friends look on as God points to these mighty creatures, the apex of God’s creation: ‘Nothing on earth is like it. … It is king over all the sons of pride’ (Job 41:33–34 own translation). The images and the text in the margins (of the engraving) are accepting of, rather than resistant to, the mystery of bounded power and violence, whether animal (Behemoth and Leviathan) or human (thee): ‘Behold now Behemoth, which I made with thee’.

The image invites the reader to recognize the kindred nature of the great beasts, the biblical human watchers, and contemporary viewers. God’s arm links all three. The three levels of God’s reality are clearly framed: the inner circle of these most awesome of animals, the intermediate oval of the human and animal, and the outer rectangle in which God and the angels frame all in all. Here all is harmony; each has its place and power, under God. Job’s relentless interrogation of the retributive theology of his friends and the justice of God are interrupted and answered in Blake’s image. Blake captures the moment of epiphany for Job: ‘I have heard of You by the hearing of the ear; but now my eye sees You’ (Job 42:5).

References

Blake, William. 1805–10. Behemoth and Leviathan. Watercolour, available at http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/1668292 [accessed 22 October 2018]

Blake, William. 1823. Illustrations of the Book of Job, ed. by Charles Eliot Norton (Boston: James R. Osgood and Co.). Available at http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/blake-blakes-illustrations-of-the-book-of-job [accessed 22 October 2018]

Anish Kapoor

Leviathan, 2011, PVC, 33.6 x 99.89 x 72.23 m, Monumenta 2011, Grand Palais, Paris; ©Anish Kapoor / All rights reserved DACS / Artimage, London and ARS, NY 2019. Photo: Dave Morgan

‘He Looks On Everything’

Commentary by Gerald West

This monumental sculpture takes the reader/viewer within Leviathan. Though the biblical text offers a largely external array of images, there are also allusions to the ‘inside’ of Leviathan. God dares us to touch (with terror), and to ‘open the doors of Leviathan’s face’ (Job 41:14 own translation).

Anish Kapoor takes up God’s challenge, enabling us to be intimate with Leviathan by inviting our touch of the polyvinyl fabric—probably less with fear than interested apprehension—and by confronting us with the interior of God’s monumental creation.

Perhaps by becoming more intimate with Leviathan, we are offered the possibility of becoming more intimate with God. By allowing Kapoor to conduct us into Leviathan, we also find ourselves conducted into a new relationship with aspects of God’s creation. Walking within Leviathan, we experience ourselves as puny and vulnerable but also present and alive. We see the world differently through the skin and the eyes of Leviathan: ‘It looks on everything that is high; it is king over all the sons of pride’ (41:34). All is reconfigured from within this body, both the world outside and we who are inside. The emotive language of Job 40:15–14 and 41:1–34 becomes an emotional experience within the interior of Kapoor’s work. And when we find our way outside, we discover that this creation (or creature) is even bigger than it had seemed from the inside.

Leviathan has texture, has an inside and an outside; Leviathan is an experience, an encounter. Indeed, as the biblical text declares, Leviathan must be ‘beheld’ by Job and readers of Job. ‘Nothing on earth is like it’ (41:33) thus becomes not only an imaginative but also a sensory reality.

The immensity of Kapoor’s Leviathan, which fills the Grand Palais in Paris, inhabiting more than 13,000 square metres of space, can help to make a sensory reality of Leviathan, the creature, and to disclose God, the creator. ‘Behold now’ says God to Job when beginning to describe Behemoth and Leviathan (40:15). Kapoor reiterates this divine summons, providing us with access to a phenomenon that is both actual and overwhelming. Like Job, perhaps, we are bewildered but transformed.

References

Menezes, Caroline. 2013. ‘Anish Kapoor: Leviathan’, Studio International: Visual Arts, Design and Architecture, https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/anish-kapoor-leviathan [accessed 31 May 2018]

http://www.marthagarzon.com/contemporary_art/2011/05/monumenta-2011-leviathan-anish-kapoor [accessed 31 May 2018]

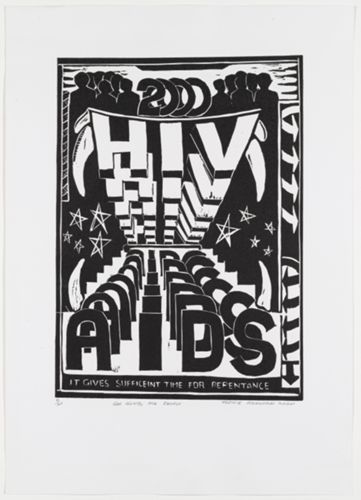

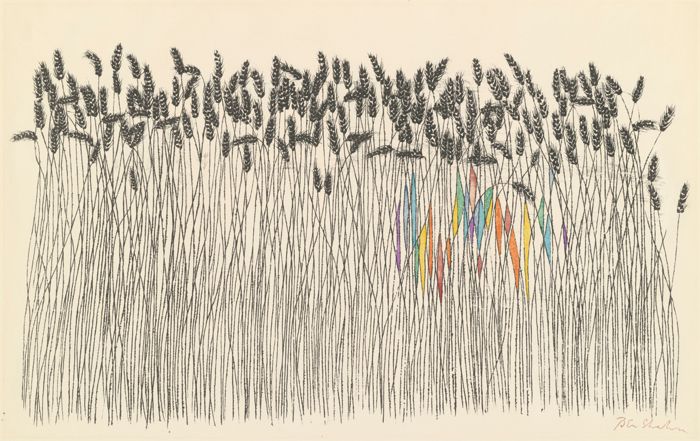

Trevor Makhoba

God Wants His People, c.2001, Linoleum cut, 418 x 302 mm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; 1110.2007.14, © Courtesy of Mrs. G. Makhoba © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

‘God Wants His People’

Commentary by Gerald West

This image is clearly theological. Both the linocut phrase ‘It gives sufficeint [sic] time for repentance’ and the artist’s title (in pencil at the bottom) ‘God wants his people’ declare a theological theme. What is not as clear is the reference to Job 40 and 41, until one remembers that isiZulu and isiXhosa Bible translations of these chapters translate Behemoth as ‘hippopotamus’ and Leviathan as ‘crocodile’.

Here Trevor Makhoba conjures a combined hippopotamus/crocodile beast, with millenarian nostrils (shaped from the number 2000) and tombstone teeth. The mouth of this great beast gapes at us. The attentive viewer is forced to take a step back, such is the power and threat of this open jaw. This image draws on the implied threat of the biblical Behemoth and Leviathan towards humans (Job 41:25, 34), and the clear incapacity of humans to control either (40:24; 41:1–8, 26–29). Indeed, this work invokes the sense in the biblical text of God’s tenuous control of these most mighty of God’s creatures: ‘He is the first of the ways of God; let his maker bring near his sword’ (Job 40:19 own translation).

In the context of a rampant HIV pandemic in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Makhoba’s homeland, the question that haunts Makhoba’s image is: ‘Is God for or against this terrifying beast?’ The night sky and the stars allude, perhaps, to the beginning of Job’s lament (Job 3) where he imagines creation undone. In his anguish Job reverses the order of creation: ‘May the day be darkness’ (3:4). The stars and the white arrows in the right-hand panel portend redemption from the ‘black gloom’ (3:5). But the black arrows point to certain destruction for those drawn into the monstrous mouth. As with Leviathan, ‘[a]round its teeth there is terror’ (41:14). However, the words of Scripture, though not from the book of Job, offer words of hope: ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness’ (2 Corinthians 12:9). ‘God wants his people’, provided they repent. Only then are we safe from Behemoth–Leviathan.

William Blake :

Behemoth and Leviathan, from Illustrations of the Book of Job, 1825–26 , Engraving

Anish Kapoor :

Leviathan, 2011 , PVC

Trevor Makhoba :

God Wants His People, c.2001 , Linoleum cut

‘Whatever Is Under the Whole Heaven Is Mine’

Comparative commentary by Gerald West

These three images offer us different ways of apprehending Job 40 and 41.

Somewhat surprisingly, given the wild unpredictability of much of the book of Job, William Blake offers us a clear sense of God’s order within each of his three ‘spheres’ or frames. Here animals, humans, and the divine each have their appointed place. What connects them is God. Blake reads the book of Job as a confirmation of God’s order and control. Behemoth and Leviathan are awe-full but constrained.

Not so for Trevor Makhoba. He experiences Behemoth and Leviathan unbound, prowling through his province and preying on African bodies. His image unleashes Behemoth and Leviathan, confronting us with the terror of their textual power made ‘flesh’. Makhoba’s beast is all mouth, the body hidden from view, just as the hippopotami and crocodiles of the rural areas of his homeland lie submerged below the surface of the waters, waiting, with only their nostrils visible. Like the HIV and AIDS pandemic, the danger of this beast is invisible. Behemoth and Leviathan lurk just below the surface of normal life, as HIV inhabits the blood beneath the skin.

Both artists invite us to be attentive; to ‘behold’. Just as Blake’s image has human watchers, so too does Makhoba’s, with silhouetted humans looking down into the gaping mouth. But the beholding differs dramatically. One is a visionary insight into cosmic order; the other a vigilance against a crouching and virulent threat.

Anish Kapoor shifts the focus from seeing to touching. His Leviathan consists of flesh-like fabric. While Makhoba’s image seemed too terrifying to touch, Kapoor’s Leviathan invites tactile encounter. But it cannot be tamed. Though drawn into and around the pulsating body of God’s ‘king’ of creation (Job 41:34), we remain dwarfed by it. Experiencing this Leviathan with our whole bodies, we are also vulnerable to the creature’s disorientating immensity. Thus Kapoor and Makhoba disturb us in different ways. Kapoor’s Leviathan swallows us up within its body, but we feel the potential presence of Makhoba’s Behemoth–Leviathan, unseen and terrible, within ours.

The palette of these artworks ranges from the sharp black and whites of Makhoba’s linocut, through the grayscale of Blake’s engraving (and the pastel colours of his watercolours), to the vibrant intense red (from the inside) and earthy-ochre (from the outside) of Kapoor’s installation. Makhoba is an accomplished oil painter, preferring bright colours in his paintings, so his choice of black and white for this work seems significant: funereal perhaps. Kapoor’s red interior allows a more life-enhancing role for Leviathan: like a womb the enveloping environment might be a place of new beginning, as the whirlwind was for Job.

The Behemoths and Leviathans of these artists demand our attention in different ways, compelling us to look carefully, unsettling us, while in important ways also incorporating us. Each work brings particular details within the biblical text to life, and each offers resources for theological reflection. God’s presence is overt in Blake, entertained in Kapoor, and hoped for in Makhoba. But each of these images, in their respective intersections with the book of Job, may help us explore not only the presence but also the nature of God. Blake assures us that God’s control is absolute; Makhoba is not so sure in the face of the terrible spectre of mass death; Kapoor wonders whether a close encounter with even the most sublimely terrible of God’s creatures may also be the occasion of both personal and collective remaking.

References

Menezes, Caroline. 2013. ‘Anish Kapoor: Leviathan’, Studio International: Visual Arts, Design and Architecture, https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/anish-kapoor-leviathan [accessed 31 May 2018]

Schoenherr, Douglas E. (ed.). 1997. Lines of Enquiry: British Prints from the David Lemon Collection (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada)

West, Gerald. 2010. ‘“God Wants His People”: Between Retribution and Redemption in Trevor Makhoba’s Engagement with HIV and AIDS’, De Arte, 45.81: 42–52

Commentaries by Gerald West