Matthew 27:32; Mark 15:21; Luke 23:26; John 19:17

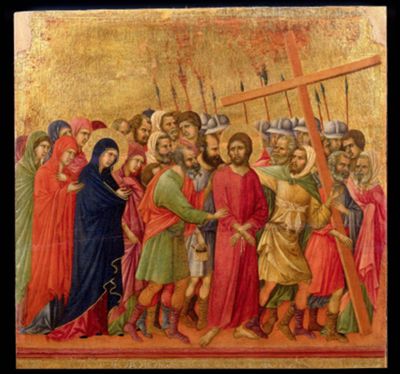

Christ on the Way to Calvary

Duccio

Christ on the way to Calvary, from the Maestà, 1308–11, Tempera and gold leaf on panel, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Mourning unto Death

Commentary by Andrew Casper

Duccio di Buoninsegna was the leading painter of the Italian city-state of Siena in the late 1200s and early 1300s. His portrayal of Christ’s journey to Calvary was one of several scenes from the Passion of Jesus that adorn the reverse of his most famous altarpiece, the Maestà, commissioned for the Cathedral of Siena. As part of a narrative sequence, Duccio designed the composition with ease of legibility as one of his foremost considerations.

To this end, Duccio’s portrayal stays close to the more extensive description of this episode in Luke 23:26–32 (as compared with the other Gospels). Christ has already been relieved of his burden of carrying the cross by Simon of Cyrene, seen on the far right. Meanwhile, Christ glances backward toward the women grouped together on the left who mourn his impending death. Among the women is the Virgin Mary, identified by her blue garment and gilded halo.

The addition of other elements stimulates the viewer’s anticipation of Christ’s later death. Gaunt and solemnly immobile, while prominent against the throngs following behind him, he is clad in red as though to foreground the blood that will be shed at his crucifixion. His hands, here bound at the wrists, are lowered—a posture which foreshadows the one he will soon assume when lying dead (albeit temporarily) in the sepulchre.

The style of this panel is consistent with late Gothic painting in Siena. It bears witness to the influence of gilded icons from Byzantium that made their way to Italy after the sack of Constantinople in 1204. These typically enriched their sacred subjects with rich material splendour—both in forms of fields of gold leaf and also in the delicate tooling used to enliven the shimmer of halos.

In this particular example, the expansive gold leaf in the background conceals the fact that this event’s historical setting was an urban one. It removes the scene from the specificity of time and place. Further, it focuses the viewer’s attention on the crowds of figures packed together in the foreground.

It is in these figures, and perhaps especially in the multitude of women wailing and lamenting Christ (Luke 23:27), that the viewer of this artwork finds his or her role. Not just as an outside spectator, but as a mournful participant from his or her own time and place of contemplation.

Jean de Wespin and Giovanni d’Enrico

Jesus Carrying the Cross (Chapel 36), 1599, Polychrome terracotta and fresco, The Sacro Monte di Varallo, Varallo Sesia, Italy; imageBROKER.com GmbH & Co. KG / Alamy Stock Photo

An Apocryphal Encounter

Commentary by Andrew Casper

This is one of the several contributions made by Jean de Wespin (Il Tabacchetti) and Giovanni d’Enrico in the late 1500s and early 1600s to the Sacro Monte di Varallo in Piedmont, Northern Italy. The ‘holy mountain’ is a pilgrimage site consisting of a series of small chapels featuring multi-media dioramas of sacred events. Visitors to the Sacro Monte have benefited for centuries from the immersive devotional experiences that they afford.

This particular scene is among the most lavish of those at the site. It is composed of crowds of figures made in polychrome terracotta exhibiting animated gestures and postures. These painted sculptures have a naturalism rarely encountered in Italian Renaissance art. They are nearly life-size, and the artist has incorporated such elements as real hair and inlaid glass eyes to evoke a vivid and hyperrealistic presence verging on the hallucinatory for viewers who encounter this scene.

The subjects featured at this site, and other sculpted sacri monti like it, usually adhere closely to the Gospel accounts of their respective stories. But especially prominent in this one is a famous episode which—though frequently portrayed by medieval and Renaissance artists—is not explicitly mentioned in any of the four Gospel accounts of Christ’s carrying the cross. This is the encounter with St Veronica, who presents Christ with a face cloth after he stumbles under the weight of the cross.

By introducing another character to the story of Christ’s way to Calvary, the Veronica legend offers additional ways for worshippers to enter into devotion to Christ’s Passion. One of those is through the object she holds in her hands. After being wiped, Christ’s face is said miraculously to have left its image adhering to the cloth. That image is here displayed by Veronica. The cloth, often called the Sudarium, the Veil of Veronica, or simply the Veronica, was believed to have been kept in Rome since the twelfth century where it became one of Christianity’s most holy and highly revered sacred relics.

Veronica, like Simon of Cyrene, embodies the compassionate onlooker. Both this apocryphal woman and this scripturally-attested man are followers of Christ and his sacrifice—emerging from the anonymity of the masses who press around the Saviour to become more intimately bound up in his story. Both provide examples after which viewers can model their own piety and empathy.

Titian

Christ on the Way to Calvary, 1560, Oil on canvas, 98 x 116 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; Copyright of the image Museo Nacional del Prado / Art Resource, NY

Christ Falls

Commentary by Andrew Casper

Titian Vecellio (1490–1576) was among the leading painters of Venice and a prolific creator of religious imagery throughout the 1500s. Titian’s composition offers us an intimate view of a particular moment within the Gospel accounts of Christ’s way to Calvary. Titian framed the scene as a close-up view of Christ stumbling under the weight of the cross. Struggling to pick himself back up, he looks over his shoulder to see Simon of Cyrene arriving to assist in lifting the cross off his shoulders (Luke 23:26).

No other details of the setting, nor the other crowds of figures mentioned in Luke’s narrative, intervene. This helps direct the viewer’s contemplation to focus only on Christ’s physical struggle and his empathetic encounter with Simon.

Titian painted a number of pictures showing Christ on the Way to Calvary. This one, dated to about 1560, comes from the end of the aged Venetian painter’s career when his style became characterized by loose and open brushwork. It is a technique that does not disguise but rather testifies to the artist’s physical activity of applying oil pigment, roughly, to the canvas. We see this most emphatically in the treatment of Christ’s robes, where thick strokes of paint articulate the garment’s undulating wrinkles and folds. In the lower right that same garment all but dissolves into almost abstract and autonomous networks of worked paint.

This approach to painting was condemned by some Italian Renaissance critics—Giorgio Vasari prominent among them—for its supposed lack of finish. Vasari accused the artist of failing to bring his works to a proper state of completion.

But, in a way that is typical of Titian’s late style, this manner of painting imparts the artist’s subjectivity—fashioned not through the detached and rote rehearsal of a standard subject, but through a spontaneity that records the moment of its very making. This makes this work far more than a studied representation of a biblical event. And knowing the artist’s heartfelt expression of piety in the religious imagery he made in the last two decades of his life, we may see here evidence of Titian’s own personal faith.

In so personalizing Christ on the Way to Calvary, Titian invites viewers, too, to share his devotion: to find in themselves the same humility, empathy, and compassion that we see Simon of Cyrene directing towards Christ in his most vulnerable state.

Duccio :

Christ on the way to Calvary, from the Maestà, 1308–11 , Tempera and gold leaf on panel

Jean de Wespin and Giovanni d’Enrico :

Jesus Carrying the Cross (Chapel 36), 1599 , Polychrome terracotta and fresco

Titian :

Christ on the Way to Calvary, 1560 , Oil on canvas

Contemplating Christ’s Final Steps

Comparative commentary by Andrew Casper

As a subject in Christian art, the episode of ‘Christ’s Way to Calvary’ is a popular one. The four Gospel accounts of this episode are sparse in details, and so offer ample room for artists to imagine unique and individualized ways of representing the narrative. The variety of figures portrayed in this long artistic tradition afford manifold opportunities for viewers’ spiritual engagement; multiple ways to articulate their role as both witnesses and participants.

While the primary focus of all four Gospels is Christ, none is identical in its description of the circumstances in which he makes his journey to Golgotha. Matthew 27:32 and Mark 15:21 merely mention that Simon of Cyrene was called upon to help carry the cross when Christ was unable to do so. John 19:17 does not even mention this—saying that Christ carried his own cross to Golgotha and nothing more. Only Luke 23:26–32 provides any detail to assist readers in imagining the scene—including the involvement of Simon of Cyrene, but also the mourning women of Jerusalem (whom Christ admonishes to hold their grief; v.28) and the two thieves who would be crucified alongside Christ. But none of these accounts elaborates upon the setting in which Christ carried the cross nor the travails he experienced while doing so. Artists therefore have to—and did—infer Christ’s physical burden and emotional agony while beaten, defiled, and humiliated as he took his final steps towards death.

These three artworks by Duccio, Titian, and Jean de Wespin and Giovannni d’Enrico, focus on different aspects of, and even different moments within, the Gospel accounts of Christ’s journey to his crucifixion. Two of them feature Christ stumbling under the weight of the cross. The other shows him standing solemnly amongst the crowds. These different portrayals, as well as their diverse stylistic choices, can be explained in part by the different devotional ends to which the artists fashioned their respective versions, and the various contexts for which they were made.

Titian’s painting is a private devotional work intended for intimate engagement, probably by a single viewer. His compositional and stylistic choices reflect those aims. Indeed, this painting arrived at the Escorial in Spain in 1574, where it was kept in King Philip II’s private oratory and, according to some sources, became one of his favoured devotional images (Falomir 2003: 202–03). Its sombre mood, dark palette, and its focus on Christ’s physical struggle—as well as the poignancy of the gaze he directs at Simon—underscore the image’s aim to induce sorrow for his agony.

Duccio’s painting, by contrast, was not only destined for the grand altarpiece of Siena Cathedral (albeit the reverse side, which was primarily accessible only to certain church officials), but was also meant to be legible within the context of a narrative series of Christ’s life. The viewer was not just meant to contemplate Christ’s journey to Golgotha by itself, but to understand its position within the broader narrative of Christ’s Passion and death that surrounds it.

Similar in this regard is the scene found at the Sacro Monte of Varallo: it too is a moment in a sequence, and other episodes from the life and death of Christ are given similar multimedia treatments. But the work is different from Duccio’s in the sort of contemplation it calls for from its viewers—the intense devotional attention that it invites; the directness of the participatory engagement elicited by the three-dimensional scene. The sculptural groups would have encouraged (and can still facilitate) vivid sensory experiences. The life-size scale, material realism, and mimetic exactitude of the works can blur the boundaries between the artifice of illusory representation and reality itself. It can thereby achieve a different form of spiritual engagement from that offered in Titian’s and Duccio’s paintings.

Of course, none of these images focuses on Christ alone, and consequently none replicates the sparse simplicity of John 19:17. They are not just about Christ. Indeed, Duccio includes the women and daughters of Jerusalem who mourn Christ’s agony and impending death (Luke 23:26–32). His and Titian’s paintings also feature Simon, who steps in to help carry the cross (Matthew 27:32, Mark 15:21, and Luke 23:26–32). De Wespin and D’Enrico insert the apocryphal story of Veronica helping to soothe Christ’s suffering, and the relic of that event that she takes away from it.

Taken together, despite all of their narrative, compositional, and stylistic differences, all three artists offer viewers opportunities to recognize their own roles in contemplating the story. They direct the viewer’s attention not just to the burden of Christ’s sacrifice, but also to figures who, like us, emerge from the shadows to enact their own individually pious reactions as they witness Christ’s travails.

References

Falomir, Miguel. 2003. Tiziano (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado), pp.266–69, available at https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/christ-on-the-way-to-calvary/8eb4c2f7-56e4-49cf-ab3e-4a23f82c718b [accessed 30 June 2023]

Commentaries by Andrew Casper