Esther 5:1–8

Esther’s Pivotal Moment

Artemisia Gentileschi

Esther before Ahasuerus, c.1626–30, Oil on canvas, 208.3 x 273.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll, 1969, 69.281, www.metmuseum.org

Feigned Feminine Fragility

Commentary by Jonathan Homrighausen

Artemisia Gentileschi was the first woman ever accepted into the Academy of the Arts of Drawing in Florence—at great personal cost. Like Esther, she succeeded in a man’s world.

Her representation of Esther before Ahasuerus includes a detail found in the Greek text but not the Hebrew: Esther fainting into her maidservants’ arms (Additions to Esther 15:7). Generally, the greatly expanded Greek version of Esther (drawn upon heavily by the Latin Vulgate) gives more psychological insight into its heroine. But at this pivotal moment when Esther seeks to win the king’s sympathy and save her fellow Jews, the narrator heightens the drama by not divulging Esther’s mental state as she faints not once, but twice.

While the text at first seems to paint Esther as a helpless damsel, Artemisia seems to suggest that Esther’s faint was the feint of an actress staging helplessness for royal sympathy. Her body remains vertical from the waist down; this supposed collapse is more of a torso twist than a real fall. Only her left leg bends; her right remains firm. The maidens stand conveniently close to her, as if choreographed, yet they do not block the king’s view of her wilting figure.

Gentileschi’s portrayal of the king also diminishes the king’s physical presence. Here he is ‘hardly more than an overly luxurious, effete adolescent’ (Soltes 2018: 75); she appears more mature (Treves 2020). His royal rod is absent. He seems to stare at her pale cleavage rather than jumping to help her. Though he is seated on a raised throne, their heads are almost level, suggesting an equality in their relationship. By depicting the king as youthful, perhaps inexperienced, Artemisia alludes to the book of Esther’s broader portrayal of Ahasuerus as weak-minded and fickle.

In suggesting that Esther merely feigned feminine weakness to win over the king, Artemisia foreshadows recent feminist readings of Esther by centuries. Her depiction of Esther as the true master of this scene, and the master of the king, suggests that behind the textual narrative’s apparently helpless heroine is a consummate actress and rhetor.

References

Soltes, Ori Z. 2018. ‘Beauty and Its Beholders: Envisioning Sarah and Esther’, in Biblical Women and the Arts, ed. by Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, Biblical Reception 5 (London: T&T Clark), pp. 57–82

Treves, Letizia. 2020. Artemisia (London: National Gallery)

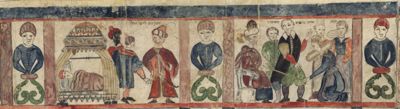

Unknown artist, Italy

Esther before Ahasuerus, from book of Esther (מגלת אסתר), 1617, Manuscript illumination, The National Library of Israel, Jerusalem; Israel Ms. Heb. 197/89=4, The National Library of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel

Esther Reenacted in Ritual

Commentary by Jonathan Homrighausen

Although the Jewish custom of reading the Scroll of Esther (or ‘Megillah’) at Purim dates back to the early rabbinic era, the custom of lavishly decorating such scrolls with ornament and illustration only began in sixteenth-century Italy. At the time of this scroll’s creation in the seventeenth century, Italian–Jewish communities emulated their Christian neighbours in both lavish artistic patronage and the Baroque style, setting off a revival in Jewish art.

Unlike the other two works in this exhibition, this illumination supplies minimal scenery. Even Ahasuerus’s throne is not especially elaborate or grand. In place of depicting the presumably large palatial setting of the biblical episode, the artist merely suggests it through the ornate Baroque floral ornament framing the scene and the scroll as a whole. Moreover, this Esther does not faint, but solemnly grips the sceptre offered to her by King Ahasuerus.

But like the other two artists in this exhibition, the illuminator of the scroll does include minor characters in the scene. Indeed, human figures fill the entire space, focusing the viewer’s attention wholly on them. Four unidentified individuals look on as Esther, seeming confident and collected in her regal purple dress, kneels before the king. A man at the centre of the composition glares at the king and tries to block Esther from grasping the sceptre. While this at first glance seems to be Haman, elsewhere in this scroll Haman wears bright red and sports a moustache. Neither does this man resemble any of the sons or courtiers of Haman as represented elsewhere in the scroll. Either way, his expression suggests that Esther had enemies in the palace, despite her efforts to hide her identity. The three other figures are uninvolved in the action—including two women of the palace, perhaps concubines. Their lack of interest suggests their ignorance of Esther’s plan.

The fact that this scroll’s figures wear the garb of the artist’s time raises the question: did the artist, or his community, see themselves as Esthers of their own era, adopting the clothing and visual styles of their Gentile neighbours even as they made Jewish art; perhaps evading thereby the scowls of their enemies? If so, then this dignified Esther, rather than the fainting Esther of the Greek and Latin versions, may point to something more than the biblical text itself: a Jewish self-image at a later point in history.

References

‘NLI Moshe ben Avraham Pescarolo Esther Scroll, Ferrara, 1616’, The Centre for Jewish art, available at https://cja.huji.ac.il/esther/browser.php?mode=set&id=66

Jan Steen

Esther before Ahasuerus, Late 1660s, Oil on panel, 106 x 83.5 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg; Entered the Hermitage between 1763 and 1773; formerly in the collection of Catherine the Great, ГЭ-878, classicpaintings / Alamy Stock Photo

A Theatrical Crowd Scene

Commentary by Jonathan Homrighausen

Although the book of Esther revolves around Haman, Ahasuerus, Mordecai, and Esther, the plot is moved along at several crucial points by the actions and words of palace courtiers, named and unnamed.

The Hebrew text mentions no background characters in this episode. The Greek Septuagint version, however, mentions Esther’s and Ahasuerus’s servants jumping to Esther’s aid as she faints before the king while approaching him to invite him to her banquet (Additions to Esther 15:7). She is risking everything to save the lives of her people from genocide for she knows full well that:

if any man or woman goes to the king inside the inner court without being called, there is but one law; all alike are to be put to death, except the one to whom the king holds out the golden scepter. (4:11)

Jan Steen’s theatrical Esther before Ahasuerus builds on the text’s slender details to create an entire court’s worth of responses. Though many people’s eyes will be led first to the illuminated figures of Esther and her maidens, this group takes up relatively little of the panel. Around her, the attentive viewer can quickly discern a great many figures rendered in darker hues, displaying a variety of reactions. In the foreground, for example, a royal scribe writes the king’s annals, so crucial later in the Esther story, while his companion looks directly at us and points to Esther (Cahill 2017: 30).

The range of reactions among the characters in this crowded composition seems to demand us to consider our own response. It poses the question: where and who are you in this story? Do you gaze in wide-eyed wonder at Esther’s bravery—or in mockery at her supposed weakness? Are you uninterested in the queen’s plight, and if so—by extension—do you fail to notice the persecuted seeking help in your own day and age; the world’s tragedies on the street and the news?

Like many Dutch painters of his day, Steen drew heavily from theatre—especially its focus on moments of reversal such as this, as the all-powerful king comes under Esther’s influence (Cahill 2017). At first glance, Steen seems to downplay Esther’s pivotal moment of winning the king’s sympathy in favour of the varied activity of a large court. But on closer inspection, he magnifies the scene through the range of courtiers’ responses, and thus he draws his viewers in.

References

Cahill, Nina. 2017. ‘Staging the Old Testament: Jan Steen and the Theatre’, in Pride and Persecution: Jan Steen’s Old Testament Scenes, by Robert Wenley, Nina Cahill, and Rosalie Van Gulick (Birmingham: Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham), pp. 20–33

Artemisia Gentileschi :

Esther before Ahasuerus, c.1626–30 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist, Italy :

Esther before Ahasuerus, from book of Esther (מגלת אסתר), 1617 , Manuscript illumination

Jan Steen :

Esther before Ahasuerus, Late 1660s , Oil on panel

Esther in Three Lenses

Comparative commentary by Jonathan Homrighausen

The book of Esther is one of the most vivid and suspenseful stories in the Bible. Its theatrical palace scenery and dramatic plot twists provide fruitful fodder for the mind’s eye and the artist’s canvas.

All three of these artworks explore possibilities particular to the visual medium, and all were made in the seventeenth century, yet they reflect the perspectives of different religions, genders, nationalities, and cultural contexts.

When looking at the elaborate staging, construction of place, and varied cast of Jan Steen’s rendition, it is unsurprising to learn that his painting style was heavily influenced by Dutch theatrical conventions of his day. Meanwhile, art historians connect Artemisia Gentileschi’s frequent portrayals of strong biblical women to her own trauma: she endured both rape and a gruelling and highly publicized trial against her assailant (Straussman-Pflanzer 2013). While her several paintings of Judith decapitating Holofernes seem to exemplify this strength in obvious ways, her Esther is differently formidable, using feigned weakness as a tool of rhetorical power in the place of physical force. Finally, the Ferrara scroll seems to connect Esther’s diasporic struggles to the Jewish community of its own day.

The three artists gathered here even draw from different texts of the book of Esther. The Megillah’s Jewish artist works from the Hebrew Masoretic text, which tells this scene in a brief two verses. The Esthers of Steen and of Artemisia, both Roman Catholic, reflect the heroine of the Latin Vulgate—a version that incorporates the earlier Greek Septuagint’s expansion of this scene into sixteen dramatic verses, elaborating on Esther’s royal garments, her inner fear, and her dramatic faint into the arms of her two maidservants. This lengthier telling of the scene, which may also derive from Josephus (Antiquities 11.6.9), is a favourite source for Early Modern European Christian paintings of Esther (Kahr 1966: 107–24), and is dubbed Addition D by modern scholars.

These different texts of Esther, corresponding to two different religious traditions, partially explain why Steen’s and Artemisia’s compositions differ from the Megillah’s. Although both the Septuagint and Josephus were originally Jewish creations, rabbinic Jewish tradition moved away from them and built its own extensive midrashic traditions around Esther—though some of the Greek additions did find their way back into Jewish tradition through the medieval Jewish chronicle Sefer Yosippon (Tabory 2012: 441–64). Esther’s faint and her maidservants who catch her do not appear in any ancient targum or midrash on Esther, and only appear in a few Jewish artistic renditions of Esther (Budzioch 2017: 420).

In short, these three works of art suggest the many different factors that have an impact on biblical readers, from gender, to culture, to variations in texts and translations. Yet in all three, the artist has fleshed out the story, adding the background cast, the scenery, and the psychological explanations that the Hebrew text of Esther leaves out.

As we reread the text after viewing the art, we can better see how the biblical narrator focuses our attention on the scene, and what that narrator chooses to tell and what not to tell. By viewing these visual renditions side by side, we can better discern the text’s omitted details and psychological ambiguities, from which the artists’ creativity begins. And in these narrative details—such as the presence of hostile or friendly courtiers, the possibility that Esther merely pretended to be helpless, or the suggestion that Ahasuerus was young and naive—we see new moral dimensions of the story, and new theological questions for those who believe that God is behind its improbable plot.

References

Budzioch, Dagmara. 2017. ‘Midrashic Tales in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Illustrated Esther Scrolls’, Kwartalnik Historii Żydów [Jewish History Quarterly] 263.3: 405–22

Kahr, Madlyn. 1966. ‘The Book of Esther in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art’ (PhD diss., New York University)

Straussman-Pflanzer, Eve. 2013. Violence & Virtue: Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago)

Tabory, Joseph. 2012. ‘Yefet in the House of Shem: The Influence of the Septuagint Translation of the Scroll of Esther on Rabbinic Literature’, in Shoshannat Yaakov: Jewish and Iranian Studies in Honor of Yaakov Elman, ed. by Shai Secunda and Steven Fine, BRLJ 35 (Leiden: Brill, 2012), pp. 441–64

Commentaries by Jonathan Homrighausen