Galatians 3:23–4:7

Heirs According to Promise

George Gittoes

The Preacher, 1995, Oil on canvas, 181 x 250 cm, The National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; NGA 2016.52, © George Gittoes

Neither Jew nor Gentile

Commentary by Rod Pattenden

In 1995 Australian artist and film maker George Gittoes was in Rwanda, documenting the work of UN peace keeping forces. This coincided with the one year anniversary of the horrendous civil war which had left over a million people dead. Inspired by revenge, local Rwandan soldiers began to attack the crowds who had gathered hoping for the protection of the UN forces. Many thousands lost their lives that day and Gittoes worked tirelessly alongside the 24 medical personnel to save lives and treat the injured. He also took photographs of the perpetrators which were later used at a war crimes tribunal.

Amongst the frightened crowd he came across a man in a yellow coat who was reading words from the Bible out loud:

This afternoon … I came into a group who were calm. Though bursts of machine gun fire surrounded them—continually getting closer with terrifying inevitability—they remained a solid congregation—bound together not by walls, but by prayer. A solitary preacher read to them from a ragged bible. He spoke in French with a thick dialect—his voice hoarse and broken—but I could recognize the Sermon on the Mount. ‘Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God’. [Matthew 5:8] (Sydney Morning Herald 1995: 14)

The figure in Gittoes’s painting directly addresses the eyes of the viewer. His gesture has the appearance of an appeal to be witnessed and remembered. The work makes reference to other works that have focused on history’s victims, such as Francisco Goya’s Third of May 1808, and countless depictions of Christ who—in the face of betrayal and violence—responded with compassion.

This preacher is a Christ figure. He testifies in a dire situation. He asks us to witness the power of love in the face of a hatred based on racial difference.

Gittoes said at the time:

[t]he Preacher, represents what I think religion should be, raise people up, make people feel human and spiritually alive and give them courage and faith. When I returned home I was carrying this terrible imagery in my head. I have a wife and two children. I didn’t want to go straight into the studio and start painting dead children. The one powerful positive image I had was the preacher. I could see him in his yellow coat and I could feel his courage. (Sydney Morning Herald 1995: 14)

References

1995. ‘Preacher takes Prize, 15th December 1995’, Sydney Morning Herald, p.14

Kara Elizabeth Walker

Christ's Entry into Journalism, 2017, Ink and pencil on paper, cut-and-pasted on painted paper, 3569 x 4978 mm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Acquired through the generosity of Agnes Gund, the Contemporary Arts Council of The Museum of Modern Art, Carol and Morton Rapp, Marnie Pillsbury, the Contemporary Drawing and Print Associates, and Committee on Drawings and Prints Fund, 198.2018, © Kara Walker; Photo: © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Neither Slave nor Free

Commentary by Rod Pattenden

This large scale drawing in ink and pencil, sets out a visual field populated with references to the African-American experience of enslavement and social marginalization. The vast scale of the work invites viewers to find their own path across its surface. Contrasting social attitudes jostle with each other. Representations of cultural icons overlap with images of violence and cruel parody. With a lynching tree hovering over them, historical figures such as Martin Luther King Jr are shown alongside trapeze artists, people in costume, Klansmen, riot police, soldiers, and the enslaved. Together they constitute a vibrant assemblage of characters from across time.

The scale and composition of the work leaves it without a focal point, as each individual element calls for the attention of the viewer. This denies us a point of rest or a single position from which to survey a clear order of things. The various elements vie for recognition and understanding, caught up in a cycle of violence and sad comedy that is repeated over and over again.

This historical parade, rendered as a painful panorama, is negotiated by the eye of the viewer looking for threads of meaning—for some form of pattern, or historical purpose; for social improvements or advances; for hope.

Viewed in the light of the protests associated with the Black Lives Matter movement of 2020, this restless image takes on new meaning: by its unfinished nature it continues to deliver a sharp contemporary challenge. The ink is still wet and the work is still being added to in an unending repetition of violence and betrayal. Around the world during 2020, aged statues in city squares were toppled. So many generous benefactors who garnered their wealth through the profits of slavery. Our history has been telling our future.

Christ’s entry into ‘Journalism’ in the title, reminds us that current history is mediated to us in ways that allow detachment, as we become viewers rather than participants or mediators of change. Where might we search for the presence of Christ? Perhaps hope is incarnated in a suffering victim, or alternatively crushed by a figure who claims the rights of white privilege. This work resonates with questions for Christian theology, asking who is orchestrating such a parade in which one’s role is determined by the colour of one’s skin? How might it be directed differently?

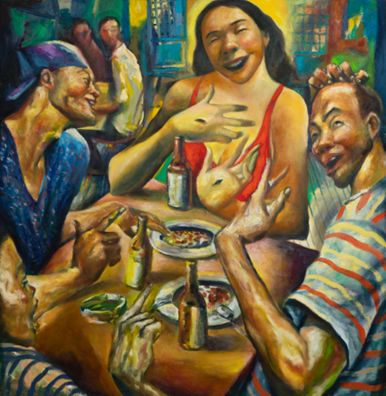

Emmanuel Garibay

Emmaus, 2012, Oil on canvas, 91 x 91 cm, Private Collection; © Emmanuel Garibay

Neither Male nor Female

Commentary by Rod Pattenden

Emmanuel Garibay is an artist from the Philippines who is known for striking images that critique the conventions of his country’s European colonial past. This work is his surprising portrayal of the events of Luke 24:13–35 in which the newly-risen Christ, unrecognized, walks to the village of Emmaus with two of his disciples. Upon arrival, he agrees to eat with them, and is finally seen and acknowledged at the breaking of the bread.

In Garibay’s work the disciples break into laughter at this recognition of Christ, and their own previous blindness. But what they see is a woman, with dark skin, in a slim red dress, eating among the ordinary workers in the village.

This work is shocking for the way it upends what those familiar with mainstream Western Art might expect. Theologically the Christian tradition would affirm that the spirit of Christ is not bound by differences of sex or gender, but is alive in the world in creative and diverse ways. Yet we had really expected a man—and probably white.

Western audiences recognize their shock at this female depiction and yet, though androgynous, we know that this is Christ: her face is haloed, and her hands bear the marks of crucifixion. The hilarity of the disciples becomes the humour, the shock, the recognition of a divine joke that has been played on the viewer’s theological and cultural expectations. Here is the embodied shock of Paul’s affirmation, ’neither male nor female’, for all are one in Jesus Christ (Galatians 3:28).

There is more. The context is not a church or holy place, but somewhere where ordinary people gather, have simple food, and drink beer. This Christ is female and—perhaps as shockingly—has dark skin. She is an indigenous Filipino, utterly different from any colonial Spanish or contemporary North American representation of power and authority. The Christ figure also wears a red café dress, a cultural convention that presents a woman who may not be considered respectable company.

Where else should we look for the living Christ, if not among the poor and marginalized? New possibilities for hope emerge as traditional icons of power are overturned. Freedom is let loose in the laughter of disciples shocked out of their conventional forms of seeing. This image laughs at the oppressive apparatus of both church and state, and locates freedom in the places where ordinary people break bread.

George Gittoes :

The Preacher, 1995 , Oil on canvas

Kara Elizabeth Walker :

Christ's Entry into Journalism, 2017 , Ink and pencil on paper, cut-and-pasted on painted paper

Emmanuel Garibay :

Emmaus, 2012 , Oil on canvas

One in Jesus Christ

Comparative commentary by Rod Pattenden

Paul’s great affirmation of oneness in Christ, irrespective of social, gender, and religious ascriptions (3:28), has continued to echo throughout Western history. It has contributed profoundly to the development of our modern understanding of the nature of the human person as an individual with inherent rights and responsibilities. Paul’s original words were uttered in religious and cultural contexts where a consideration of the human person as an individual was largely unknown. A sense of self was determined by the designations of one’s relations to family, tribe, or race; through birth and upbringing. Identity was largely understood in terms of who you belonged to.

The implications of this insight have taken a long period of time to unfold. They have resulted in the breaking down of enmity across religious and cultural lines, the ending of slavery, the bringing of equal rights to women and men, and access to services and rights under law to people on the margins of society, including those with disabilities, queer folk, asylum seekers, and refugees. In the Church, vociferous arguments have been fought over slavery, women’s ordination, and same sex marriage, based on definitions dearly held about the perceived nature of the human person. Paul’s view is that no one individual is disqualified from bearing the image of God irrespective of the conditions of their birth, their appearance, or their social trajectory.

The rich diversity of human persons gives full incarnational expression to the Christian affirmation of oneness in Christ. In the face of the many ways humans are grouped and separated, categorized, marginalized, or privileged, this is a magnificent invitation that knows no boundary. It is powerfully expressed through the shock of Emmanuel Garibay’s Christ figure, a dark-skinned female in a red dress, at home in a café in the local village. This is the eucharistic meal—the central liturgical action of the church throughout history where people, irrespective of their social, religious, and cultural backgrounds are welcome. Garibay echoes this table of hospitality in his work, and invites us beyond our cultural prejudices and fears so that we may welcome the stranger, and find friendship even with the stranger in us.

In the torrid environment of war and sectarian violence George Gittoes provides an eye-witness account of an encounter with a black ‘Christ’, a preacher in a yellow coat. In the midst of the dehumanizing forces of fear and prejudice one person chooses to embody courage and compassion. This figure, through calm action and the use of familiar words, enables a community of people to live out what is to be truly human, rather than respond in fear or acts of reprisal. It echoes the deep cry of creation for reconciliation and embodies the figure of Christ as peacemaker.

Kara Walker invites us to reconsider our history and to scrutinize those icons we hold dear, even those we have believed would save us. The Christ figure is entangled in our history. Does Christ operate as a source of liberation and hope for all people, or has this figure appeared as an icon of power that has conquered, oppressed, and held people captive? We now live in a time where humans have an impact on every aspect of this planet’s ongoing development. Humans rule the world, warm the environment, engender violence, maintain tribal allegiances, sometimes find reconciliation, and yearn for peace and hope. Where do we find Christ present as a source of hope adequate to address the future, crowded as it is with prospects of climate change, nationalistic competition for resources, and ongoing cycles of human conflict and terrorism?

The vision of the oneness in Christ that quickened the mind of Paul the Apostle offers a possibility of justice in the world for all people based on their equal worth as part of God’s creation. This exhibition offers visual evidence that Christ might also be found beyond the margins of our traditions and comfortable habits. This surprising, shocking, and unexpected stranger is the familiar Christ. Given the visual evidence, the incarnation of Christ might announce itself as a simple moment of surprise. Christ standing next to me, in the shoes of the stranger, my neighbour.

Commentaries by Rod Pattenden