Exodus 31:12–17

Honouring Sacred Time

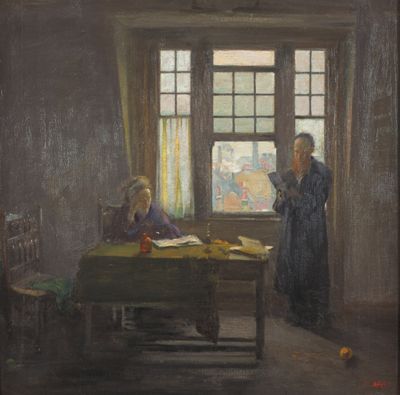

Isidor Kaufmann

Friday Evening, c.1920, Oil on canvas, 72.7 x 91.1 cm, The Jewish Museum, New York; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. M. R. Schweitzer, JM 4-63, TheJewishMuseum.org

The Welcoming of the Sabbath

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

And the Lord said to Moses, “Say to the people of Israel, ‘You shall keep my sabbaths, for this is a sign between me and you throughout your generations, that you may know that I, the Lord, sanctify you’”. (Exodus 31:12–13)

Isidor Kaufmann’s Friday Evening is a composition replete with contrasts. Traditional in its subject matter, it is Modernist in style. At the time when key Modernist movements were beginning to emerge in Western Europe, Isidor Kaufmann made his name travelling throughout Eastern Europe, painting genre scenes of Jewish life and religious observance.

In Friday Evening, the sole figure—a female in traditional garb—calls to mind seventeenth-century Dutch genre paintings. However, unlike those interior scenes, where the women depicted are often engaged in mundane domestic activities, this figure gives an impression of piety through her contemplative gaze and solitude.

Her table displays the necessary ritual objects for the start of Shabbat: two candles in candlesticks, a kiddish cup for wine, and (it can be inferred) two loaves of challah at the back of the table covered with a napkin. The candles are lit—an obligation equally expected of men and women—indicating sundown has occurred. Yet the bread remains covered, implying the Sabbath meal has not yet begun. And indeed, the woman appears to be in a state of waiting, with a downcast gaze, clasped hands, and a position adjacent to, rather than facing, the table.

The Shabbat candles, cup, and covered loaves are replicated through the compositional device of the mirror, which, interestingly, appears to reflect only these ritual objects and nothing else. These series of pairs, including the two wall sconces, serve as counterpoints to the solitary figure, as does the empty second chair.

Compositionally striking is the array of white, off-white, and beige tones Kaufmann employs. He creates a sense of three dimensionality through his use of these varied hues and an expressionistic painting technique. The predominant light tones are contrasted by the figure’s mauve dress, while the formality of the room, with its elegant ritual and decorative objects, is belied by the imperfect, creased tablecloth, the most clearly articulated lines in the composition.

Even with its apparent contradictions, Friday Evening conveys the sanctity referred to in Exodus 31:13, as the figure ensures the holiness of the Sabbath is preserved through the continuity of ritual.

Alfred Wolmark

Sabbath Afternoon, c.1909–10, Oil on canvas, 77.5 x 77.5 cm, The Ben Uri Gallery & Museum, London; Acquired in 2013 with the assistance of the HLF, the V&A Purchase Grant Fund and Art Fund, 2013-02, ©️ Ben Uri Collection / Bridgeman Images

Immersion in Torah Study

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

Therefore the people of Israel shall keep the sabbath, observing the sabbath throughout their generations, as a perpetual covenant. It is a sign for ever between me and the people of Israel that in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day he rested, and was refreshed. (Exodus 31:16–17)

Exodus 31:16–17 comprises the Hebrew prayer V’shamru, which is sung on Friday evening at the Shabbat dinner table, on Saturday morning during the liturgical service, and throughout the Sabbath day. It beseeches the Israelites to ‘guard’ or ‘protect’ the Sabbath as a reminder of their everlasting covenant with God (Berlin and Brettler 1999: 182). ‘The Sabbath serves as a sign of Israel’s relationship with God because it commemorates God’s own actions and, in observing it, Israel follows His example’.

As Rabbi Evan Moffic noted: ‘rabbis…saw the reading of the Torah on Shabbat as a reenactment of the establishment of the covenant between God and Israel when God revealed the Torah at Mount Sinai’ (Moffic n.d.). Recitation of V’shamru allows for the re-creation of this holy time and space.

Immersing oneself in Torah study, like that depicted in Alfred Wolmark’s Sabbath Afternoon, is a traditional Sabbath day practice, and one of the fundamental ways to guard and perpetuate the covenant.

Wolmark, himself Jewish, emigrated to England from Poland and trained at the Royal Academy Schools in the 1890s. Despite his classical training, Wolmark’s style was deeply influenced by emerging Modernist trends. What makes the painting especially interesting—and distinguishes it from more conventional depictions of the Sabbath day—is its setting: a domestic scene amidst a modern, industrial cityscape. The smokestack, a product and emblem of the Industrial Revolution, stands in stark contrast to the traditional appearance of the Orthodox man by the window, and to the woman seated at the table, who appears to be just as immersed in textual study as he is. The ancient ritual of observing Shabbat endures, even against this twentieth-century urban backdrop.

Just as the Sabbath binds sacred time and space, the figures, though separated by their individual absorption in learning, are unified by their shared commitment to maintaining the covenant that is Shabbat.

References

Berlin, Adele and Marc Zvi Brettler. 1999. The Jewish Study Bible (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Rabbi Moffic, Evan. 2024. ‘V’Shamru: Guarding the Divine Covenant’, www.myjewishlearning.com [accessed 8 February 2024]

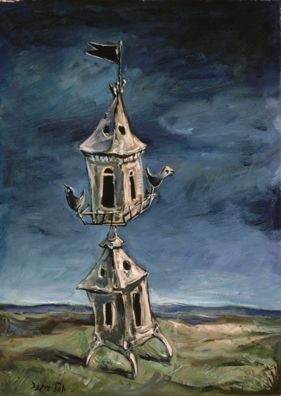

Yosl Bergner

Spice Container, mid 1970s, Oil on canvas, 45.6 x 33.3 cm, The Jewish Museum, New York; Gift of Cheryl and Henry Welt, 1988-26, ©️ Yosl Bergner / Copyright Agency. Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2024

The Transition of Time

Commentary by Adrianne Rubin

Austrian-born, Israeli painter Yosl Bergner created still-life scenes often situated outside of the domestic sphere, set against illogical backdrops. Spice Container is one such example.

It represents a key element of the Havdalah ritual. Havdalah means ‘separation’ or ‘distinction’, and in the context of the Sabbath, it refers to the conclusion of Shabbat on Saturday evening and the impending return to the ordinary workweek. It differentiates between sacred time and the mundane.

Havdalah is typically observed at home and may take place once three stars are visible in the night sky. While the ritual is brief, it is active, multi-sensory, and rich in symbolism. Wine is consumed to embody the joy of Shabbat; a spice box, filled with sweet-smelling spices, like cinnamon and clove, is shaken so the scent can serve as a reminder of the lingering sweetness of the Sabbath; and a braided, multi-wick candle is lighted and passed around to emphasize the difference between light and darkness. Blessings are said that underscore and give thanks for such distinctions.

All aspects of the Havdalah service speak to Exodus 31:17: the importance of being ‘refreshed’ or renewed by the Sabbath. Interestingly, Shabbat ends in similar ways to how it begins—with wine, candle(s), and blessings—indicating it is as important to commemorate the sacred day’s conclusion as it is to mark its beginning.

Rabbinic teachings put forth the idea that on Shabbat, every person is given an extra soul, the neshama yeterah. which they relinquish at Havdalah. ‘When Shabbat draws to a close, the extra soul withdraws, leaving the mundane soul behind. Some believe that aromas are the only aspect of the material world that a soul can enjoy, and spices provide consolation to the remaining soul’ (Perlis 2005:13). While Havdalah spice boxes can take many forms, the tower-like shape represented in Bergner’s painting is traditional.

While Bergner’s placement of this domestic, ritual object outdoors is unconventional, his depiction of a darkening sky is undoubtedly an intentional allusion to the object’s context in time, if not in space.

References

Perlis, Natasha. 2005. ‘Spice Roots: An Introduction to the History and Role of Spice Boxes’, in Scents of Purpose: Artists Interpret the Spice Box (San Francisco: Contemporary Jewish Museum)

Isidor Kaufmann :

Friday Evening, c.1920 , Oil on canvas

Alfred Wolmark :

Sabbath Afternoon, c.1909–10 , Oil on canvas

Yosl Bergner :

Spice Container, mid 1970s , Oil on canvas

Remember and Observe the Sabbath

Comparative commentary by Adrianne Rubin

The Ten Commandments—or The Decalogue—are the foundation of Jewish and Christian ethical belief and behaviour. It is perhaps unsurprising, given their supremacy, that they appear more than once within the Hebrew Bible. They are first delivered by God to Moses verbally in Exodus 20, where what we know as the Fourth Commandment is stated:

Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labour, and do all your work; but the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God; in it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your manservant, or your maidservant, or your cattle, or the sojourner within your gates; for in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day and hallowed it. (Exodus 20:8–11).

The Sabbath day mirrors God’s own day of rest after the six days of creation. In this way, ‘the Sabbath was built into creation itself’ (Stein 2005: 478), and it is, therefore, sacrosanct. This Commandment is so fundamental that it explicitly states that no person—irrespective of their station in life—is exempt from remembering the Sabbath and abstaining from work. Even livestock cannot be put to work on this holy day. The same Commandment is echoed in Deuteronomy, where Moses tells the Israelites: ‘Observe the sabbath day, to keep it holy, as the Lord your God commanded you’ (5:12).

The distinction between the mandates to ‘remember’ and to ‘observe’ the Sabbath has been the subject of much biblical commentary. According to Rashi, an eleventh-century French rabbi and perhaps the best-known medieval commentator on the Hebrew Bible, ‘Both of them (zachor and shamor) were spoken in one utterance and as one word and were heard in one hearing’ (Borovitz n.d.). The double instruction within the single Commandment is emblematized in the lighting of two Shabbat candles on Friday evenings.

Exodus 31 introduces a further level of complexity when it states of the Sabbath: ‘every one who profanes it shall be put to death; whoever does any work on it, that soul shall be cut off from among his people … whoever does any work on the sabbath day shall be put to death’ (vv.14–15). Unlike Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, in Exodus 31 there are punitive consequences for failing to keep the Sabbath.

The context of this passage is noteworthy, for the Israelites are about to receive The Ten Commandments on the tablets given to Moses by God. They are building the Tabernacle, the moveable sanctuary God directed Moses to construct for the Israelites to use as a place of worship as they wandered through the desert; a place where God could commune with His people. Upon threat of ostracization and even death, this sacred work is meant to cease in order to honour Shabbat. Holy time supersedes holy space. As twentieth-century theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote: ‘Six days a week we live under the tyranny of things of space: on the Sabbath we try to become attuned to the holiness in time’ (Stein 2005: 503).

The three paintings that comprise this exhibition are twentieth-century interpretations of the millennia-old Jewish tradition of observing Shabbat—the Sabbath—in accordance with the dictate conveyed in Exodus 31:12–17. Rather than focussing on the punitive nature of verses 14–15, the selected paintings highlight the holy decree to remember and observe the Sabbath. As Rabbi Amy Perlin has written:

[I]t is not until Exodus 31 that we get the full reason for keeping the Sabbath. It is not the punishment of death in 31:14 for profaning the Sabbath, or being excommunicated from the Jewish people for working on the Sabbath.… God tells us that Shabbat is a SIGN … that God consecrated us; that God made us holy. (Perlin n.d.)

These artworks are a visual representation of the progression of time through this sacred day—from Erev Shabbat on Friday evening, to Shabbat afternoon on Saturday, to Havdalah on Saturday evening. The context-specific, human-centric works of Isidor Kaufmann and Alfred Wolmark are complemented by Yosl Bergner’s seemingly acontextual depiction of a single ritual object.

Viewed collectively, these works represent the essential elements of remembering and observing Shabbat, and they amplify the perennial importance of honouring sacred time.

References

Borovitz, Jeremy. 2024. ‘Observe versus Remember’, www.sefaria.org [accessed 24 February 2024]

Perlin, Amy. ‘V’Shamru: Mo’ed and Meaning, Parashat Emor’, https://www.tbs-online.org [accessed 28 February 2024]

Stein, David E.S. (ed.). 2005. The Torah: A Modern Commentary, Revised Edition (New York: URJ Press)

Commentaries by Adrianne Rubin