1 Timothy 3

Bishops and Deacons

Unknown Byzantine artist

Mass of Saint Basil, 11th century, Fresco, Church of St Sophia, Ohrid, Macedonia; akg-images

The Officiating Bishop

Commentary by Magdalena Skoblar

Basil of Caesarea was a fourth-century bishop who composed a liturgy that bears his name and is still used in the Orthodox Church. He was regarded as a model bishop by other contemporary theologians including his brother Gregory (who was bishop of Nyssa), and Gregory of Nazianzus. They praised his moral virtues and ecclesiastical leadership which manifested themselves, among other things, through his insistence that the recommendations of 1 Timothy 3:2–3 be upheld when taking on new ministers. Basil called for ‘a very careful investigation’ of their conduct so as ‘to learn if they were not railers, or drunkards, or quick to quarrel’ (Letter 54).

This fresco which shows Basil performing his liturgy is located in the sanctuary of the church of St Sophia at Ohrid. Its exact location is on the north wall just off the apse where the Communion of the Apostles is depicted on the same level.

The officiating scene continues the story from the previous fresco in which Basil receives divine inspiration from Christ who has appeared to him in a dream. Dressed in episcopal attire, Basil is shown bowing before an altar with the bread, chalice, and gospels on it. In his hands is a scroll inscribed with the opening words of a prayer from the liturgy he wrote: ‘Lord, our God, You created us [and brought us into this life]’. This prayer is read just after the ceremony of the Great Entrance during which the officiating priest enters the sanctuary through the iconostasis.

This is the first and only time such a scene has been depicted in Byzantine art. It coincided with the final rift between the Western and Eastern Church of 1054, which had been brewing over their respective use of unleavened and leavened bread in the Eucharist. In fact, the person who commissioned the frescoes, Archbishop Leo, was a key figure in the dispute. This scene, emphasising the mystery of the Eucharist and harking back to the origins of Byzantine liturgy, made it clear that the eucharistic practices of the Eastern Church were instituted by the ascended Christ himself through the agency of Basil.

The one ‘vindicated in the Spirit [and] taken up in glory’ (v.16) is shown working through his ministers to ensure that the Church remains genuinely ‘the church of the living God’ (v.15).

References

Deferrari, Roy J. (ed.). 1926. Saint Basil: The Letters, vol. 1, Loeb Classical Library, 190 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), pp. 342–47 [343]

Lidov, Alexei. 1998. ‘Byzantine Church Decoration and the Great Schism of 1054’, Byzantion, 68.2: 381–405

Rapp, Claudia. 2013. Holy Bishops in Late Antiquity: The Nature of Christian Leadership in an Age of Transition (Los Angeles: University of California Press)

Sterk, Andrea. 1998. ‘On Basil, Moses, and the Model Bishop: The Cappadocian Legacy of Leadership’, Church History, 67.2: 227–53

Todić, Branislav. 2012. ‘Arhiepiskop Lav—tvorac ikonografskog programa fresaka u Svetoj Sofiji Ohridskoj’, in Vizantijski svet na Balkanu, ed. by Bojana Krsmanović, Ljubomir Maksimović, and Radivoj Radić (Belgrade: Vizantološki institut), pp. 119–37

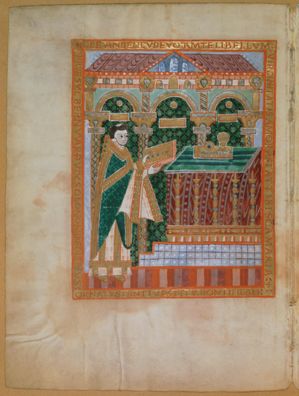

Unknown German artist

Dedication image of St Bernward, from The Bernward Gospels, c.1015, Illuminated manuscript, Dom-Museum Hildesheim, Germany; DS 18, fol. 16v, © Bildarchiv Foto Marburg / Dom-Museum Hildesheim / Art Resource, NY

Appointed by God’s Election

Commentary by Magdalena Skoblar

Now a bishop must be above reproach, the husband of one wife, temperate, sensible, dignified, hospitable, an apt teacher, no drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and no lover of money. He must manage his own household well, keeping his children submissive and respectful in every way. (1 Timothy 3:2–4)

In the tenth century bishops of Hildesheim in lower Saxony were appointed by the Holy Roman Emperor. The ruling Ottonian dynasty of that time was Saxon and they elevated Hildesheim to be their home bishopric. Bishop Bernward, depicted here with the manuscript he had commissioned, was a Saxon nobleman who started his career as a chaplain at the imperial court. He was also tutor to Emperor Otto III at the age of six.

His credentials, therefore, went beyond the simple requirements of 1 Timothy 3 and extended into the sphere of privileged family connections. Bernward’s episcopate at Hildesheim in the late tenth and the early eleventh century was marked by significant acts of patronage. The Bernward Gospels—the gospel book he donated to St Michael’s Abbey, which he founded and chose for his burial site—were part of this beneficence.

The bishop had himself represented in a two-page dedication scene. We see him here presenting the gospels to the Virgin and Child, who are depicted on the facing page (not shown here). He is wearing sumptuous liturgical vestments and is standing in a church, next to an altar with the eucharistic bread and chalice set upon it. This is liturgical portraiture at its best: Bernward’s sacramental authority is acknowledged by Christ and his mother.

In the dedicatory inscription framing the page on which he is depicted, the bishop refers to himself as ‘only scarcely worthy of this name, and of the adornment of such great episcopal vestment’. In a similar self-definition from a different source, Bernward had stated he was ‘appointed bishop by God’s election and not of [his] own merit’.

Such non-individualistic views are related to theological interpretations of 1 Timothy 3:6 by Augustine, Jerome, and John Chrysostom, warning against pride. They focused their attention on the admonition that while the office of bishop is a noble task, those who aspire to it should not be ‘puffed up with conceit and fall into the condemnation of the devil’.

References

Gorday, Peter J. (ed.). 2000. Colossians, 1–2 Thessalonians, 1–2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, New Testament, 9 (Downers Grove: Inter Varsity Press)

Kingsley, Jennifer P. 2014. The Bernward Gospels: Art, Memory, and the Episcopate in Medieval Germany (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press)

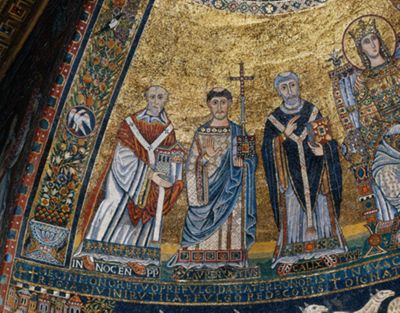

Unknown Italian artist

Innocent II, Saint Lawrence, and Saint Callixtus (Apse mosaic detail from Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere), 12th century, Mosaic, Basilica di Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome; Scala / Art Resource, NY

The Treasures of the Church

Commentary by Magdalena Skoblar

What virtues should bishops and deacons embody? And how might first-century instructions to the Church’s earliest ‘overseers’, recorded in 1 Timothy 3, speak down the centuries to their powerful and wealthy successors in episcopal office?

The election of Innocent II as pope in 1130 was controversial and he was ousted by a rival pope, Anacletus II. Upon his return to Rome, eight years later, Innocent II had to strengthen his position. The building campaign at Santa Maria in Trastevere, the title church of his rival before he seized the papal throne, was part of this project. In addition, Trastevere was the area of Rome in which Innocent II grew up.

The church of Santa Maria was completely rebuilt by the pope in the early 1140s. He had the new apse decorated with a spectacular mosaic depicting Christ and the Virgin seated on the same throne and surrounded by figures belonging to different ecclesiastical ranks. Innocent II himself appears holding the model of the basilica at the far left next to St Lawrence, a third-century Roman deacon, and St Callixtus I, a third-century pope who was associated with this very church.

The presence of St Lawrence in this group, though he did not have a direct link with Trastevere, is not surprising. He was a third-century Roman deacon whose dedication to the charitable work of his office earned him popularity among the faithful of Rome. As a deacon at the Lateran, his duty was to manage its material goods and distribute alms. When the city’s prefect requested, he hand over to him the treasures of the church, St Lawrence gave them to the needy as alms. He then presented the poor to the prefect and said, ‘These are the treasures of the Church’ (Ambrose of Milan, De officiis 2.140).

It was his embodiment of not being ‘greedy for gain’ (1 Timothy 3:8)—a virtue required of deacons—that made St Lawrence good company for Pope Innocent II, who had to prove himself to the locals.

References

Davidson, Ivor J. (ed.). 2002. Ambrose of Milan: De officiis, vol. 1/2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 347

Kinney, Dale. 2016. ‘The Image of a Building: Santa Maria in Trastevere’, California Italian Studies, 6.1, available: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3fp5z3gz [accessed 20 July 2020]

Unknown Byzantine artist :

Mass of Saint Basil, 11th century , Fresco

Unknown German artist :

Dedication image of St Bernward, from The Bernward Gospels, c.1015 , Illuminated manuscript

Unknown Italian artist :

Innocent II, Saint Lawrence, and Saint Callixtus (Apse mosaic detail from Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere), 12th century , Mosaic

Caring for God’s Church

Comparative commentary by Magdalena Skoblar

Most denominations of the world’s largest religion—Christianity—organize themselves through networks of bishops. Their role evolved from the ministry of oversight (episkopē) exercised in the very early days of the Church’s life. The earliest ‘person specification’ for this episcopal role (and also for that of deacons) can be found in 1 Timothy 3. Historically attributed to St Paul, this text reflects the realities of the first-century Church, when bishops and deacons could marry and have children.

How they ran their households was one of the key credentials the candidates for either role had to have. Only those who managed their households well could ‘care for God’s church’ (1 Timothy 3:5). Further emphasis is placed on temperance in wine drinking and lack of greed for money, while kindness, composure, and seriousness are also identified as desirable personality traits. In this early period, women could be deacons. A female deacon, Phoebe, is recorded at Cenchreae (modern Kechries near Corinth) in Romans 16:1–2, and two more were mentioned by Pliny the Younger in the early second century (Madigan 2011: 26).

While 1 Timothy 3 does not state who appoints bishops, it seems clear that the selection does not rest with lay authorities. However, once Emperor Constantine I legalized Christianity in 313 CE and Theodosius I proclaimed it the state religion in 380 CE, the state began to get involved. By the eleventh century there was a full-blown struggle for power known as the Investiture Controversy.

The Germanic rulers of the Holy Roman Empire frequently appointed family members as bishops (something popes started to object to from the 1070s). Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim, who commissioned The Bernward Gospels, is a perfect example. Related as he was to the ruling Saxon dynasty, it is no surprise that the precious gospel book he donated to the abbey of St Michael is imbued with privilege. Bernward had founded the abbey himself and he wanted to be buried in it.

By the twelfth century, the papacy gained the upper hand in the conflict over the appointment of bishops. But, since many bishops were de facto princes of the state with wives, children, and large estates, their attention was often turned to worldly matters at the expense of spiritual ones. The First Lateran Council, held in 1122, codified the separation of ecclesiastical and lay affairs and forbade clerical marriage.

This was more easily said than done. Nevertheless, the Second Lateran Council, held in 1139, reiterated the main points of the First. This council was convened by Pope Innocent II who was responsible for the rebuilding of the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, the area of Rome he was from. He had himself depicted next to the deacon St Lawrence, a popular Roman saint, in the new apse mosaic. St Lawrence’s commitment to the poor cost him his life. His inclusion in the apse mosaic of the Santa Maria in Trastevere by Pope Innocent II cements him as a model for all deacons to follow in a time of religious reform.

The primary role of a deacon, as it evolved, was to assist a bishop or priest in the performance of the liturgy. The fresco from the church of St Sophia at Ohrid shows the saintly bishop Basil of Caesarea officiating before an altar while assisted by deacons in what is the inauguration of the liturgy he wrote. But this, too, is a visual appeal to saintly prototypes in a time of turbulent religious politics.

The works of art in this exhibition originated in the individual efforts of three very different bishops. The instructions from 1 Timothy 3:2–3 that a bishop must be temperate and gentle instead of quarrelsome and materialistic do not seem to have been ideals that were easy to embody in their respective contexts. Rival popes and contested elections, such as that of Innocent II, were at odds with the specification that ‘a bishop must be above reproach’ (1 Timothy 3:2). The election of Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim had more to do with his privilege than with him desiring a noble task (1 Timothy 3:1), and the wealth he was surrounded with is evident from his portrait in The Bernward Gospels. Archbishop Leo of Ohrid did not refrain from quarrelling with his Western peers despite honouring Basil of Caesarea—who himself had adhered strictly to the stipulations from 1 Timothy 3:2–7—in his frescoes.

What drove all of them, though, was the canonical vision of the Church as ‘the pillar and bulwark of the truth’ (1 Timothy 3:15) to whose service they were bound.

References

Kingsley, Jennifer P. 2014. The Bernward Gospels: Art, Memory, and the Episcopate in Medieval Germany (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press)

Kinney, Dale. 2002. ‘The Apse Mosaic of Santa Maria in Trastevere’, in Reading Medieval Images: The Art Historian and the Object, ed. by Elizabeth Sears and Thelma K. Thomas (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press)

Madigan, Kevin. 2011. Ordained Women in the Early Church (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press)

Todić, Branislav. 2012. ‘Arhiepiskop Lav—tvorac ikonografskog programa fresaka u Svetoj Sofiji Ohridskoj’, in Vizantijski svet na Balkanu, ed. by Bojana Krsmanović, Ljubomir Maksimović, and Radivoj Radić (Belgrade: Vizantološki institut), pp. 119–37

Commentaries by Magdalena Skoblar