1 Corinthians 15:35–58

Bodily Resurrection

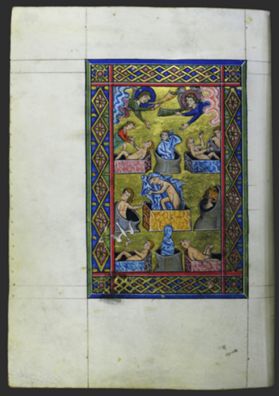

Unknown German artist

General Resurrection, from the Bamberg-Eichstätt Psalter, c.1255, Tempera on vellum, 248 x 175 mm, Stiftsbibliothek, Melk; Cod. 1903 (olim 1833) fol. 109v, Courtesy of the Stiftsbibliothek, Melk

Putting on Incorruption

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

What happens to a dead body? Can what is corrupted be made complete? Paul writes to a congregation in Corinth keen to know the answers, and in this miniature from a thirteenth-century German psalter, the artist takes on such questions directly, illuminating 1 Corinthians 15:51–53 in particular.

The anonymous illuminator shows the angels’ trumpet blasts rousing the dead from their tombs, including the central figure, who rises in his shroud (in the lowest register), disentangles himself (middle register), and puts on the garment of salvation (top register). This sequence literalizes the image of ‘putting on’ that Paul uses in relation to the general resurrection, of salvation as a vesture donned anew (1 Corinthians 15:53–54; cf. 2 Corinthians 5:4; Isaiah 61:10). Tertullian, too, uses clothing metaphors in The Resurrection of the Flesh, writing that we will first be ‘reinvested with the flesh’ we lost to dismemberment and/or putrefaction, then we will receive ‘the supervestment of immortality’ (ch. 42).

This first reclothing (‘with the flesh’) is an implication of Paul’s words that our artist is unabashed in pursuing. The two flanking figures at the bottom receive for reattachment their missing limbs that had been devoured by birds and beasts—an arm here, a leg there—and are helped out of their tombs in the top register by fellow saints.

It is this body, these bones, that will rise. All the material parts of self that have decayed, been cut off, swallowed and digested, and/or scattered in death will be reconstituted in the end. In Tertullian’s words, from ‘the maws of beasts, and the crops of birds, and the stomachs of fishes, and time’s own great paunch itself’, people’s bodies will be ‘rehabilitated from corruption to integrity, from a shattered to a solid state, from an empty to a full condition’ (The Resurrection of the Flesh, 4)—much like the dry bones in Ezekiel 37.

The resurrection is not some disembodied event in which our souls alone rise to God. Salvation is of the body as much as it is of the soul, a victory not only over sin but over mortality (permanent cessation) and corruption (decay). We rise whole.

References

Tertullian. On the Resurrection of the Flesh. 1885. Trans. by Peter Holmes, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 3 (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing)

Unknown Italian artist

Sarcophagus of Saint Theodore, 5th century (lid, late 7th century), Marble, 2.05 m long, Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna; Cameraphoto Arte, Venice / Art Resource, NY

Life Latent in Death

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

Made in the fifth century, this sarcophagus was reused in the seventh as the tomb of Theodore, archbishop of Ravenna from roughly 677–691. The city was a grand one: capital of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century. But the Latin inscription on the sarcophagus is simple: ‘Here rests in peace Theodore, v.b. [vir bonus = good man], archbishop’.

Like much early Christian funerary art, this tomb adapts Roman victory emblems to convey a message of triumph over death through Christ, throwing into relief the Isaianic line that Paul quotes: ‘Death is swallowed up in victory’ (1 Corinthians 15:54; cf. Isaiah 25:8).

The centrepiece of the tomb’s front face is a monogram made up of the superimposed Greek letters chi (Χ) and rho (Ρ), the first two letters in the title Christos (ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ) and therefore shorthand for ‘Jesus Christ’. Hanging from the arms of the chi are an alpha (Α) and omega (Ω), which allude to Christ as the beginning and the end of all things (cf. Revelation 22:13). This Christogram is repeated on the barrelled lid, encircled by a laurel wreath (a symbol of victory), with cross variations on either side—the cross being the ultimate symbol of death transposed into life.

Flanking the Chi-Rho on the sarcophagus are peacocks, which, because of an ancient belief that their flesh does not decay, came to symbolize incorruptibility, resurrection, renewal. Behind them unfurls a twisting vegetal pattern that recalls Paul’s seed metaphor: buried in the earth, the Christian will one day sprout forth with new life. And these are no generic vine scrolls; they are grapevines, another pagan art motif repurposed by Christians as a symbol of the life-giving blood of Christ, by which the redeemed enter heaven.

These images, carved directly onto a saint’s burial chamber, mark it as a site of future resurrection and therefore preach hope from the side aisle of the church where the tomb has lain since Theodore’s interment. The seed of a body that lies inside will one day be raised ‘imperishable’, ‘in glory’, and ‘in power’ (1 Corinthians 15:42–43). This is the promise that all God’s faithful can claim.

References

Schoolman, Edward M. 2013. ‘Reassessing the Sarcophagi of Ravenna’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 67: 49–74

Stanley Spencer

The Resurrection, Cookham, 1924–27, Oil on canvas, 274.3 x 548.6 cm, Tate; Acquisition Presented by Lord Duveen 1927, N04239, © Estate of Stanley Spencer / Bridgeman Images; © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Resurrection Now

Commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

The Resurrection, Cookham portrays the last day unfolding peacefully in the churchyard of the small Berkshire village that Stanley Spencer called home. No cataclysm here, just ‘the joy of the earth giving birth to joy’, Spencer wrote in a letter to Hilda Carline (1924), as people casually awake from death as if from a night’s sleep.

In the centre, a nude Spencer reclines against his tombstone next to his brother-in-law, Richard Carline, and behind lawyer Henry Slesser, a friend and patron. Two men nearby rise out from under hoods of earth, while a woman in a floral-patterned dress emerges through a parted sea of moon-daisies. To the right, women share notes left on their grave wreaths, while on the far left, the newly risen read their tombstone inscriptions with amusement. Others peek out over the edge of their coffins, or brush dirt clods from each other’s clothes. Spencer’s wife, Hilda, appears three times: clambering onto the deck of a Thames riverboat, sniffing a sunflower (while a prone, tweed-suited Spencer admires her), and lying on a nest of ivy.

The apex of this monumental painting is the rose-bowered porch, under which sits a matronly Christ holding three babies, his hair stroked by God the Father. Their presence is unassuming.

Arising to their new eternal state, the people in The Resurrection, Cookham could well exclaim along with Paul, ‘O death, where is thy sting?’ (1 Corinthians 15:55), and join in his gratitude. The law, whose tablets Moses displays from his open casket adjacent to the church porch, has no power to condemn (v.56), for Christ has fulfilled every jot and tittle, and these ordinary villagers reap the benefits.

The resurrection of the saints is a topic that fascinated Spencer, and he painted it many times, stressing the continuity between this world and the next. Unlike many of his contemporaries in the interwar period, who inclined toward cynicism or despair, Spencer maintained a profoundly hope-filled religiosity, delighting in the promise of salvation that he saw burning like Moses’s bush from every corner of daily life.

References

Spencer, Stanley. 1924. ‘Letter to Hilda Carline’, quoted in Stanley Spencer at War by Richard Carline (London: Faber & Faber, 1978)

http://www.stanleyspencer.co.uk/cookres.htm [accessed 14 October 2018]

Ibbett, Victoria. 2016. ‘The theme of resurrection in Stanley Spencer’s work, 28 March 2016’. Art UK. https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-theme-of-resurrection-in-stanley-spencers-work [accessed 14 October 2018]

Unknown German artist :

General Resurrection, from the Bamberg-Eichstätt Psalter, c.1255 , Tempera on vellum

Unknown Italian artist :

Sarcophagus of Saint Theodore, 5th century (lid, late 7th century) , Marble

Stanley Spencer :

The Resurrection, Cookham, 1924–27 , Oil on canvas

At the Last Trump

Comparative commentary by Victoria Emily Jones

In 1 Corinthians 15:35, Paul launches into the heart of his dispute with the church at Corinth: the means and meaning of a resurrection body.

He concedes it is a mystery, yet he attempts to unpack it a little, using a seed metaphor to stress both continuity and change: the selfsame matter that is buried is what flowers forth from the ground, though in a more fully developed, more glorious form. That is, the resurrection body is new in quality but not substance; it arises out of what was sown (vv.36–38).

Foliated patterns show up frequently in early Christian art, especially on funerary objects, like the sarcophagus of Archbishop Theodore of Ravenna. Drawn from Graeco-Roman decoration, acanthus and vine motifs took on new meaning for Christians, who often used them to express the promise of resurrection. Dead flesh, whether contained in stone or dissolved into the earth, may be thought of as inanimate, but in the Christian understanding, it is pregnant with potential, a site of fertility—and it is Christ who empowers the growth. Christ is the ‘firstfruits’, Paul says in verse 20, of a cosmic harvest, of the new creation. He has risen, as we shall rise.

Christian orthodoxy has always insisted on the self as a psychosomatic unity—body and soul. Resurrection, therefore, must include both, for, as Tertullian asserts, ‘If God raises not men entire, he raises not the dead’ (The Resurrection of the Flesh, 57). While early Christian art tended to express the hope of future resurrection emblematically or allegorically, medieval art took a more direct and literal approach, showing whole persons, embodied and ensouled, rising from their graves to be with God on the last day. To emphasize the triumph of integrity over partition, the scene sometimes includes animals regurgitating the body parts of the rising dead that they had eaten. Resurrection had to include reassemblage.

Originating in the post-iconoclastic East and the Carolingian–Ottonian West, this iconographic motif found its fullest development in Greece, the Balkans, and Russia, though a fine example is found in the Bamberg-Eichstätt Psalter held at Melk Abbey. Such images reflect the belief among Christians that even if swallowed, digested, made into alien flesh, excreted, or rotted, their body parts were still theirs and would one day be gathered up by God and reunited with their frames.

Beginning in the twelfth century, the general resurrection was increasingly subordinated to broader narrative themes, such as the Crucifixion or the Last Judgement, with Christ taking centre stage. Images from the latter grouping usually focus not on disentombment but on the division of the saved and the damned. Within such a schema, Renaissance artists tended to stress the ethereal splendour of the glorified body or the natural beauty of regenerated flesh.

Paul is sometimes misread as rejecting a bodily resurrection, but nothing could be further from the truth. As the Bamberg-Eichstätt Psalter delights in showing us, we will not divest ourselves of our humanity at the last trump; we will shed only our grave clothes, to be clothed instead by heavenly glory. So when Paul says ‘flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God’ (v.50), he is referring to our present, ordinary, bound-to-rot bodies—the ‘natural body’ of verse 44. But those bodies will be transformed into incorruptible ones, ones that cannot suffer or die or decompose and that are animated, through and through, by the Creator’s own Spirit—a ‘spiritual body’. Paul clearly modelled his ideas on the resurrection of the saints after the resurrection of Christ, who rose in a body that was the one he lived and died in (as indicated by the empty tomb) and yet was transfigured.

The terrestrial and celestial are conflated in The Resurrection, Cookham, a modern painting by Stanley Spencer that sets the event in an English churchyard. Here Spencer’s family, friends, and neighbours wake from their tombs, bearing not only the glory of the first Adam, ‘the man of dust’, but now too the glory of the second, ‘the man of heaven’ (v.49), Christ—for they are now imperishable, immortal!

Such grand endowments, and yet the people assume them unceremoniously; if there’s any fanfare, it occurs outside the picture. For those who, Spirit-empowered, are ‘always abounding in the work of the Lord’ (v.58), heaven does not so much shock as delight—and can already be experienced in the present. For Spencer, the fruits of resurrection are tasted whenever we are awakened to the glory and grace of God that surrounds us.

References

Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1995. The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200–1336 (New York: Columbia University Press)

Tertullian. On the Resurrection of the Flesh. 1885. Trans. by Peter Holmes, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 3 (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing)

Commentaries by Victoria Emily Jones