Matthew 2:13–15

The Flight to Egypt

William Holman Hunt

The Triumph of the Innocents, 1883–84, Oil on canvas, 156.2 x 254 cm, Tate; Acquisition Presented by Sir John Middlemore Bt 1918, N03334, © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Revelation by Dream

Commentary by Ian Boxall

There is a dreamlike quality to William Holman Hunt’s depiction of the flight, particularly in the presence of the holy innocents joining the travellers on their journey towards Egypt.

Neither Joseph nor the donkey seem aware of this mysterious band of travellers which now surrounds them. The infant Christ, by contrast, sees his fellow infants clearly, and reaches out to them in solidarity. The innocents, however, though presumably aware of Christ’s presence, are more concerned with investigating their new existence, or resuming the games cruelly interrupted by their murderers. Mary smiles, as she looks downwards, her maternal gaze apparently directed towards her newly-expanded family.

The children themselves are in various stages of ‘reality’, those at the upper left barely awake from their own dreaming. Do they exist only in a visionary world, or also in our world?

The large bubble in the centre foreground contains an image of the tree of life, a promise of paradise restored. But bubbles can so easily be burst; hence their frequent use in Vanitas paintings as symbols of transience. Is this, then, just a dream? Or might Hunt be challenging that qualifying just? For it is as the result of a dream that Joseph flees to Egypt. Another dream directs the eastern Magi to return home ‘by another way’, thus enabling Christ’s escape from Herod (Matthew 2:12). Pilate’s wife will later be troubled by a dream about the adult Christ, though her warnings will fail to preserve him from death (Matthew 27:19). Matthew’s Gospel reiterates how dreams are part of the very fabric of how God communicates in this world. Hunt’s painting likewise proposes that it may be in the world of dreams that one comes to see the world as it truly is.

Unexpected Companions

Commentary by Ian Boxall

In Matthew’s story, the departure of the Holy Family from Bethlehem echoes with more tragic sounds. Cries of distraught mothers, weeping for dead children. Artists generally keep these two narratives separate. Yet William Holman Hunt’s painting insists on pairing these two events which the evangelist has also closely interwoven. Or rather, Hunt imagines the continuation of the story of these dead innocents, understood since the early church as the first martyrs for Christ, his first companions in suffering. Already, Christ’s death is foreshadowed in the bloody slaughter of innocent babies, too young to understand their fate. But already, too, these children share in his resurrection and his victory, and now join the Holy Family on the road to safety.

Hunt (an English artist who travelled to the Middle East to research his painting) has made this connection with Easter explicit, by locating the flight in April, sixteen months after the Nativity. Springtime in the Holy Land is evoked by the flowers and the fruit. As our eyes move across the canvas, the solidity of resurrection life becomes increasingly evident. Three cherubic infants wake from the sleep of death at the top left. In the centre foreground, below Mary and Jesus, a more robust child examines the wound caused by the soldier’s sword, now healed in his glorified body. The infants at the front of the triumphal procession lead the way confidently, while those bringing up the rear exemplify their role as sacrificial victims (symbolized by their garlands of flowers) and martyrs now rising to new life (which Hunt has conveyed by their ‘branches of blossoming trees’; Hunt 1885: 9). The stream they paddle in becomes a great flood, the streams of the eternal life they now enjoy.

In this painting, rich in typology, these children prefigure all future Christian martyrs. Hunt has thereby offered a vivid pictorial answer to the apostle Paul’s rhetorical question: ‘O death, where is thy sting?’ (1 Corinthians 15:55).

References

Hunt, William Holman. 1885. The Triumph of the Innocents (London)

Vittore Carpaccio

The Flight into Egypt, c.1515, Oil on panel, 74 x 113 cm, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.28, Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Reading the Landscape

Commentary by Ian Boxall

The Flight into Egypt provided an opportunity for Vittore Carpaccio, like other Venetian artists of his generation (e.g. Giovanni Bellini, Madonna of the Meadow, c.1500, National Gallery, London), to experiment with idealized landscapes. The overall impact is impressive: rolling hills; jagged peaks; elegant trees; water calm as a millpond. But this landscape does far more than allow Carpaccio to showcase his artistic skills. There are hints of older biblical stories here, just as Old Testament narratives already saturate the Gospel text.

In the background on the far left of the panel, a prominent rugged mountain appears behind the vibrant tree which connects heaven and earth, the divine and the human. Is this merely a nod in the direction of the Dolomite Mountains, bordering the Veneto countryside to the north? Or does it recall that great mountain, Mount Sinai, the place of encounter between God and Moses after the departure from Egypt?

In the centre of the composition, a bridge straddles the river, reminding the viewer that water is a barrier, but one which can be crossed. God’s people passed through the water dry-shod as they left the land of Egypt on their Exodus journey to freedom. Later, they would cross the River Jordan, to enter the land of promise. The adult Jesus will also come to the Jordan to be baptized, on the verge of his public ministry. Carpaccio seems to have understood this well: Christ is the new Israel, whose journey to Egypt is but the first stage in a new Exodus, whereby he will ‘save his people from their sins’ (Matthew 1:21).

But there is more. Joseph, veering off from the road, tramples on lush greenery, a common symbol of Edenic paradise in visual art (e.g. Giovanni di Paolo, The Annunciation and Expulsion from Eden, c.1435, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC). Carpaccio’s richly symbolic landscape invites the following question, as it already hints at possible answers: what might this journey, ostensibly a flight from a paranoid tyrant, ultimately make possible?

References

Boskovits, Miklós, and David Alan Brown. 2003. Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century (Washington: National Gallery of Art)

A Calm Flight

Commentary by Ian Boxall

Matthew alone tells the story of Mary, Joseph, and Jesus fleeing to Egypt to escape the murderous King Herod. But what is the appropriate mood for contemplating this story? For Vittore Carpaccio, the note of urgent escape from death has receded far into the background. The pace of the journey has slowed. Neither Joseph nor the plodding donkey seem in any hurry. The stillness of the landscape, and the calm surface of the river, also evoke a sense of tranquillity for the viewer. There is time to rest, to linger. For God, not Herod, is ultimately in control. God has initiated the escape into Egypt, and God will bring Christ, his Son, out of Egypt once again.

In the Jewish and early Christian memory, Egypt, ‘the house of bondage’, was also the place of refuge. Countless Jews across the centuries had found a safe welcome among the people of Egypt (including, ironically, Herod himself). The same will hold true for the Holy Family. Yet Carpaccio has also left us with hints of that darker background story, fearful flight from danger. The face of the child appears disturbed as he gazes out at the viewer, as if seeking reassurance, or warning us of what is still to come. His mother, meanwhile, looks down mournfully at her child, her eyelids lowered, the corners of her mouth downturned. It is as if she has already become the Mother of Sorrows, standing at the foot of the cross. One tree, on the far right of the panel, is leafless and lifeless, evoking the ‘tree of shame’ (the cross) on which the adult Christ will hang on his return to the land of Israel. For Carpaccio, as for the evangelist Matthew, not even God’s Son is immune from fear, suffering, and death. His beginning foreshadows his end.

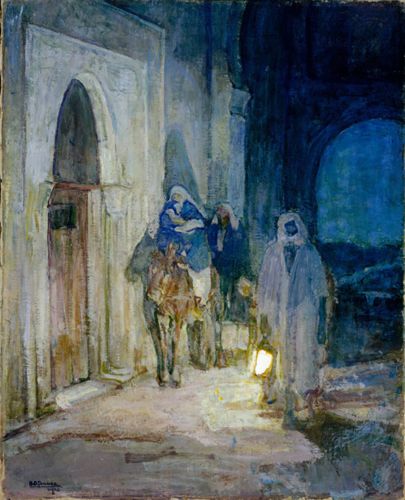

Henry Ossawa Tanner

Flight Into Egypt, 1923, Oil on canvas, 73.7 x 66 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2001, 2001.402a, www.metmuseum.org

A Flight by Night

Commentary by Ian Boxall

The journey of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph to the land of Egypt takes place under the cover of darkness. The fact that it happens ‘by night’ (Matthew 2:14) underscores the urgent note of danger and the threat of death. As the angel announces to Joseph, Herod is seeking to ‘destroy’ the child (Matthew 2:13).

Henry Ossawa Tanner was haunted by this story of flight, shaped by his formative years in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, of which his father was a bishop. He painted no less than fifteen versions of the story. Here, the fugitive character of the Holy Family is clearly foregrounded. With strong shades of blue and the use of shadows to intensify the drama, Tanner heightens the sense of forced migration. Mary’s donkey keeps close to the wall, moving slowly as if to avoid detection. The child is kept close to his mother’s breast, safely secured in her cloak, almost invisible. Joseph brings up the rear, fulfilling his traditional role as protector of the Holy Family. This is a family on the run, their ultimate destination uncertain.

Yet there are also visual clues that the fugitive family will find a ready welcome amongst the strangers they encounter. First, they are escorted by an anonymous figure, leading them through the darkened streets. The intensity of the light emanating from the lamp he carries, illuminating their path, is a reminder that this child too will be a ‘great light’ for the people dwelling in darkness (Matthew 4:16, quoting Isaiah 9:2). Second, the location of this scene is uncertain. Is it Bethlehem? Yet the family has apparently just passed through the gateway (suggested by the arch just visible in the background) into the town. More likely, then, they have arrived at their first port of call, offering a temporary respite from the dangers of Herod’s henchmen.

References

Harper, Jennifer J. 1992. ‘The Early Religious Paintings of Henry Ossawa Tanner: A Study of the Influences of Church, Family, and Era’, American Art, 6.4: 69–85

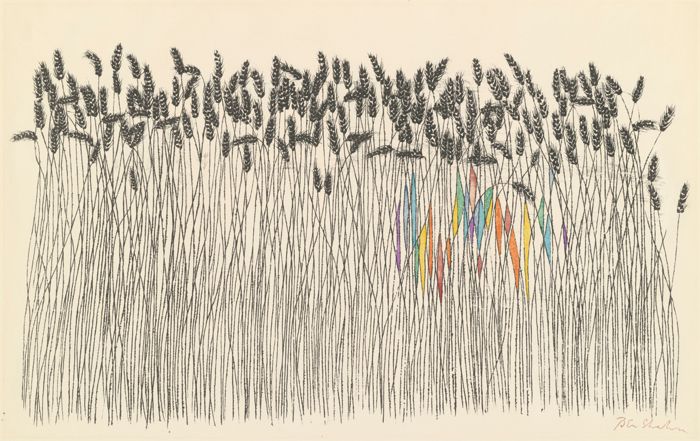

William Holman Hunt :

The Triumph of the Innocents, 1883–84 , Oil on canvas

Vittore Carpaccio :

The Flight into Egypt, c.1515 , Oil on panel

Henry Ossawa Tanner :

Flight Into Egypt, 1923 , Oil on canvas

Participating in the Journey

Comparative commentary by Ian Boxall

Journeys do things to people. Journeys can be literally life-changing, like the transformative experience of pilgrimage. But journeys can also be frightening, marked by uncertainty and anxiety, whose outcome and ultimate destination is in doubt. The flight into Egypt, now etched firmly on the Christian imagination, contains all these possibilities, and more.

Matthew’s narrative is elusive about so many aspects of this journey from Bethlehem to Egypt: its route, length, how the family were received at their destination, even the mode of transport (although the iconographic tradition almost universally introduces a donkey). It is precisely this elusiveness, however, which has enabled visual artists to explore the story in very different ways. Visual art is especially strong on that dimension of the biblical text often downplayed in scholarly commentary: inviting reader or viewer participation. This journey of a family of three becomes a journey in which others are at liberty to participate, according to their own particular circumstances. This raises the question: whose journey is it?

Vittore Carpaccio has grasped the connection between this journey and a more ancient journey: that of God’s people Israel. Matthew the evangelist had already emphasized this by evoking several Old Testament narratives. Jacob/Israel and his family, going down to Egypt to escape famine (Genesis 46). The Israelites, coming out of the slavery of Egypt at the Exodus, an event explicitly recalled in the prophecy that Matthew cites: ‘Out of Egypt have I called my son’ (Matthew 2:15, quoting Hosea 11:1). Moses, fleeing Egypt to Midian (Exodus 2), only to return to lead the people from slavery to freedom. For the evangelist, this child embodies the whole history of the people into which he was born. Carpaccio has taken this even further, evoking also the lush green of the Garden of Eden in the grass on which Joseph tramples. The journey recalls the story of all humanity, created in the image and likeness of God, that likeness tarnished by sin and brokenness. This child is also the Second Adam, who will restore what was lost.

For William Holman Hunt, the journey of an infant fugitive has become the triumphal journey of the infant victors. Rewriting Matthew’s story, Hunt offers a bold commentary on that interwoven story of the holy innocents. The brutal slaughter of babies by a paranoid tyrant is re-imagined as a journey which turns the world’s assumptions upside down. This child, not Herod, is the king riding in triumph with his conquering armies. Even as a child on the run, his triumphal entry into Jerusalem as an adult is being anticipated. Almost hidden by the crowd of innocents to the left of Hunt’s painting is a second animal, the donkey’s colt. Matthew’s Gospel alone recounts that it was on two such animals that Jesus entered Jerusalem in the days before his crucifixion (Matthew 21:1–9). In Hunt’s composition, the children carry branches, as will those who welcome Christ on that fateful day in Jerusalem. This is the journey of the ‘little ones’, the ‘least of these my brothers and sisters’, the children to whom the kingdom of heaven belongs (Matthew 18:1–5, 10–14; 19:13–15; 25:40, 45).

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Holy Family invites participation from others who likewise find themselves in the position of migrants and fugitives. Migrants like Tanner’s own mother, a former slave forced to move to the northern United States as a child (Harper 1992: 79). In his painting, the faces of all three characters are indistinct, and surely deliberately so. This family could be any refugee family, forced to flee suddenly from the security of home and relatives. Indeed, flight from war, poverty, or persecution often renders those affected ‘faceless’, anonymous, statistics rather than names. The shadows Tanner casts on Jesus, Mary, and Joseph recall the shadowy existence of those forced to flee from certain death, or to hide from threatening authorities. It is the welcome of strangers, like the equally anonymous guide with the lamp, his face obscured by his headdress, which is able to restore the gift of personhood. Tanner’s visual interpretation offers the hope of places of temporary respite, communities where the fugitive can find a welcome, regain their name, and establish new relationships of family and friendship. The paradigm is set by Matthew’s story, where Jesus, referred to anonymously as simply ‘the child’, is ultimately revealed as a child-in-relationship: ‘Out of Egypt have I called my son’. These words, originally spoken about God’s ‘son’ Israel (Hosea 11:1), now find a deeper fulfilment in God’s Son Jesus, whose journey is one of profound solidarity with his brothers and sisters.

References

Boskovits, Miklós, and David Alan Brown. 2003. Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century (Washington: National Gallery of Art)

Harper, Jennifer J. 1992. ‘The Early Religious Paintings of Henry Ossawa Tanner: A Study of the Influences of Church, Family, and Era’, American Art, 6.4: 69–85

Hunt, William Holman. 1885. The Triumph of the Innocents (London)

Luz, Ulrich. 2007. Matthew 1–7: A Commentary, Hermeneia, Rev. ed., trans. by James E. Crouch (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

O’Kane, Martin. 2002. ‘The Flight into Egypt: Icon of Refuge for the H(a)unted’, in Borders, Boundaries, and the Bible, ed. by Martin O’Kane (London: Sheffield Academic Press), pp. 15–60

Commentaries by Ian Boxall