Exodus 32

The Golden Calf

William de Brailes

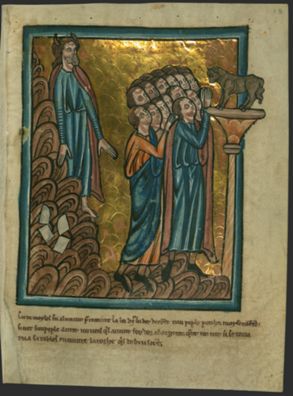

The Israelites Worship the Golden Calf, from Bible pictures by William de Brailes, c.1250, Illumination on parchment, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; MS Bible Pictures, shelf mark W.106, fol. 13r, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

All that Glisters

Commentary by Natalie Carnes

The unfaithful in this medieval illustration by William de Brailes worship in stillness. There is no hint of the pre-festival revelry suggested by Scripture (Exodus 32:5, 6) in the sober worshippers. Despite idolatry’s long association with sexual immorality, de Brailes imagines this moment of idol worship devoid of sensuality. His illustration suggests a subtler critique of how the senses go awry.

While the worshippers are modestly dressed and solemnly composed, their eyes betray their idolatry. They are all fixed in an identical, unbroken gaze at the golden calf. With their heads craned upwards, they are literally a ‘stiff-necked people’ (Exodus 32:9). They have given themselves over to what much of the Christian tradition, following Augustine’s gloss on 1 John 2:16, calls ‘the lust of the eyes’.

But this is a strange lust. Where the calf in the scriptural story was made from gold earrings (Exodus 32:2–4), the calf in this image is brown, the same shade as the horns growing out of Moses’s head (a common way of representing Moses in this scene, resulting from the Vulgate’s translation of Moses’s ‘shining’ in the descent account of Exodus 34:29 as Moses’s ‘horns’). The most visually enticing aspect of the scene is the gold-leaf background, made from the same material as the calf described in Scripture. Might this colour choice further distance idolatry from sensuality, as if to affirm that the problem of idolatry lies not in gazing at gold any more than idolatry comes necessarily coupled with sexual immorality? The trouble with idolatry, this image seems to imply, lies not in the senses; nor is the solution to idolatry the repudiation of pleasure that comes by way of them. Instead of denying sensual energies, this illustration proposes to redirect them by using gold—not to mark an idol but the background—thus evoking by it the divine presence uncontained by any particular object.

References

Augustine. Confessions, Book 10, chs 30, 35.

Imaging the Word

Commentary by Natalie Carnes

What does it mean to look at an image about worshipping an image? Does it not expose the reader to the seductions of images, recreating a scene of visual temptation? But here the image is safe. According to the dominant medieval justification for images, this illustration exemplifies an image in its proper role: as a sacred book for the illiterate.

Where Greek-speaking Christendom determined the fate of the image in 787 at the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Second Council of Nicaea), Latin-speaking Christendom initially rejected that Council, which they learned about through a poorly-translated document. King Charlemagne then commissioned the Libri Carolini to respond to the Council, refuting its justification of images and insisting that images have no advantage over words. Their proper place, the document insists, is to instruct or aid in memory, in service of words and text.

The image here even gives the words that it is in service to through an inscription at the bottom. Written in Old French, it reads: ‘When Moses went to the mountain to receive the Law, God said to him, “Go down. Your people sin.” Moses descended and saw his people adoring a calf, which they made of gold and silver. When he saw this, he grew angry at them [and] hurled his tablets against the rock so that they broke.’

With its inscription at the bottom, placement in a book, and service to a Scripture story, this illustrated leaf is a safe image for the viewer, who is encouraged to look at the golden calf the way Moses does, as sin, and reject its power. Moses’s hands are not raised in prayer or veneration but gesture emphatically down, his right hand pointing toward the tablets of the Ten Commandments, broken in an ‘anger [that] burned hot’ (Exodus 32:19). The viewer who holds this image, which is about the size of a paperback book, will find herself holding a text where images play a supporting role, not competing with words but augmenting them, extending their power.

References

'Walters Ms. W.106, Bible pictures by William de Brailes', www.thedigitalwalters.org [accessed 17 September 2018]

Nicolas Poussin

The Adoration of the Golden Calf, 1633–34, Oil on canvas, 153.4 x 211.8 cm, The National Gallery, London; Bought with a contribution from The Art Fund, 1945, NG5597, © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Danger and Therapy

Commentary by Natalie Carnes

The viewer’s eye is drawn both to the gleaming calf that commands the top half of Nicolas Poussin’s Adoration of the Golden Calf (1633–34) and to the worshippers circling that calf in dancing adoration. The movement, energy, and crowdedness of the bottom half stand in tension with the stillness and relative emptiness of the top half. Below, the arms of the worshippers stretch out to one another and up toward the calf, while above, the calf’s hoof, necklace, and eyeline all point back down, and so the gaze circulates between these two sights: the unmoving, dead idol and the lively ones giving themselves over to it.

It is easy to miss Moses coming down the mountain in dark fury, his tablet raised. This is not the shining Moses who descends Sinai for the second time in Exodus 34 but the Moses described in Exodus 32, descending unnoticed to the dancing and noise (vv.17–19). Placed far in the background, Moses is so much smaller than the revellers and the calf, and so much more obscure. It is easy for the eye to glide over this one who bears divine presence and instead circle with the dancers, moving between their revelry and the idol’s bright presence. As art historian Richard Neer (2006) has argued, this is an image that warns about the dangers of images, about how they can tempt us to devote ourselves to false divinities. In rendering the golden calf so visually appealing, Poussin shows the viewer how easily her eyes are drawn to idols.

But, of course, this is not simply an iconoclastic message. Poussin warns about images, not verbally but visually. This painting may perform a sort of therapy, helping us to see God better in the world; teaching us to look in the shadows for the divine presence descending; exhorting us to wait patiently for the glorious presence and content ourselves, in this time of waiting, with a God who may come in shadows and traces.

References

Neer, Richard T. 2006. ‘Poussin and the Ethics of Imitation’, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 51/52: 297–344

Francis Picabia

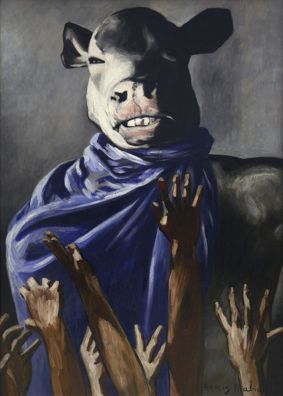

L’Adoration du veau (Adoration of the Calf), 1941–42, Oil on board, 106 x 76.2 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; AM 2007-198, Philippe Migeat © CNAC/MNAM/Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Blind Power

Commentary by Natalie Carnes

Draped in blue cloth, Francis Picabia’s calf is not golden. Nor is it clear that it is humanly-made. The calf’s grey, muscular torso, evokes classical marble sculptures of the Minotaur, but its pink-tinged nose suggests life. Its teeth are bared crookedly and menacingly, though it offers no attention to the objects it threatens. Its eye—the one that is not obscured by shadow—looks off to the side, half-closed. What kind of idol is this?

Based on a photograph of a dead calf by Erwin Blumenfeld (The Minotaur or The Dictator c.1937), Francis Picabia’s painting Adoration of the Calf (1941–42) interprets the biblical scene of idolatry loosely. Important details have been changed from both the description in the scriptural text and the tradition of golden calf paintings. Gone are the sumptuous golds of medieval and Renaissance interpretations of the scene. The worshippers have become mere hands and arms, extended in adoration. The divinity they adore is not intelligent, but it is clearly powerful. Its muscular figure, its regal blue garment, the way it dominates the scene, the way the canvas is itself over one metre high—they suggest literally brutish political force. This is an idol of blind power.

The role of sight, in Picabia’s painting, is inverted. Where many have interpreted the golden calf story as a parable about the dangers of sight, Picabia’s painting offers a visual warning about the dangers of not seeing. Blindness abounds: it is not clear the worshippers see the calf (since we can’t see their eyes). The calf certainly does not seem to see the people, or anything with much focus or clarity. The painting in this way warns of the golden calves that arise in the political sphere, playing on our fears and draping themselves in the costumes of legitimate governance. To see them for what they are, that is the hope to which the painting exhorts us.

William de Brailes :

The Israelites Worship the Golden Calf, from Bible pictures by William de Brailes, c.1250 , Illumination on parchment

Nicolas Poussin :

The Adoration of the Golden Calf, 1633–34 , Oil on canvas

Francis Picabia :

L’Adoration du veau (Adoration of the Calf), 1941–42 , Oil on board

Images and Idols

Comparative commentary by Natalie Carnes

As the command forbidding graven images is given to Moses at the top of Sinai, it is at the same time broken at the mountain’s base by God’s people, who make and worship a golden calf. Seeing the people break the command, Moses angrily smashes the stone tablet on which it is written. The moment is remembered in both the Jewish and Christian traditions as the paradigmatic scene of idolatry.

How did Christianity, a tradition with such a strong prohibition regarding images, go on to integrate them into worship? One answer, given by German picture theorist Horst Bredekamp (2010), is that the Christian image-makers did not leave that anxiety behind, but took it with them, expressing it in the images themselves. The images, in other words, communicate a prohibition against worshipping images. They warn and even attempt to guard against the threat of idolatry.

Of the three objects, Nicolas Poussin’s painting Adoration of the Calf (1633–34) betrays the anxiety about images most obviously. Having absorbed and redirected the anxieties about images in the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, Poussin’s painting is a piece of visual irony. It warns of the dangers of idolatry by foregrounding the bright, large, and captivating idol and idol-worshippers. He renders divine presence, by contrast, in the shadowy margins of the canvas, where Moses comes down the mountain in darkness. Poussin’s Moses does not gleam and shine with an obvious and glorious divine presence, for divine presence, in this image, must be sought, pursued, and discerned. By drawing the viewer’s eye to the idol rather than the divine presence, Poussin’s image exposes to the viewer her own propensity to idolatry, as if to rehabilitate her as a beholder of the divine.

But this is quite different than the Moses shining (‘horned’, as the Vulgate has it) in glory, in the illuminated manuscript by William de Brailes centuries earlier (c.1250). The contrasts with Poussin’s image are striking. In de Brailes’s illustration, first, the calf’s presence is diminished. Second, greater visual prominence is given to Moses. Third, gold suffuses the background rather than the idol. While this image, too, exhibits worry about the viewer confusing an idol with divine presence, it performs its corrective, its ‘therapy’, differently than Poussin’s painting. The gold stretches out across all creation, rather than marking only the calf, which pales in comparison, thus reminding the viewer where true glory does and does not lie. De Brailes’s illustration draws the viewer’s eye, not to expose its vulnerability to idolatry but to keep it safe from temptation. Further securing the eye from danger, an inscription interprets the illustration at the bottom of the page. The image here extends, rather than displaces, the power of the word. Thus the illustration follows the dominant justification for images in medieval Western Christianity: that images work in tandem with words.

Francis Picabia’s painting (1941–42) differs from the others in two important respects. First, where de Brailes’s and Poussin’s depictions work by suggesting a difference between worshippers in these images and the beholders of these images, which buffer the beholders from idolatry’s snares, Picabia’s painting implicates the beholder in the position of the worshippers. We can see only the arms of the worshippers, as if we are placed among the throng.

Second, Picabia’s painting contrasts with the other two in that it presents a type of idolatry that comes by way of neglecting sight, or attending to it poorly. Picabia’s calf figures a literally brutish political power. The danger for the worshippers is not that they will be ensnared by sight. They are, after all, only hands and arms in the painting. The danger is that they—that we—will not look closely enough, past the trappings of governance, to realize that they adore a leader who also does not see, does not understand. The danger in Picabia’s interpretation of the calf is an idolatry born not of sight, but of wilfully not seeing.

Together these images raise a complex set of questions about idols and sight. Poussin and de Brailes press us to ask: when are images faithful to the divine, and when do they tempt us to betray the divine, making idols when we should wait for the divine presence descending to us? When does a gaze want wrongly to see, to master by sight the divinity it should wait for in darkness? Picabia’s painting adds to these, provoking us to ask: when is a gaze wrongly blind to what it worships? Can we be so captivated by tyrants and power that we fail to see what is happening right in front of our eyes?

References

Carnes, Natalie. 2017. Image and Presence: A Christological Reflection on Iconoclasm and Iconophilia (Stanford: Stanford University Press)

Bredekamp, Horst. 2010. Theorie des Bildakts (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag AG)

Commentaries by Natalie Carnes