Psalm 130

Out of the Depths

Michael Arad and Peter Walker

Reflecting Absence, 2011, Granite and bronze, The Memorial Plaza, Manhattan, New York; Pygmalion Karatzas / Arcaid / Bridgeman Images

Depth Dimensions

Commentary by Michael Banner

Out of the depths I cry to thee, O Lord. (Psalm 130)

In the Old Testament the depths often refer to the depths of the sea (Psalm 69:2, 14; Isaiah 51:10; Ezekiel 27:34), and are a figure for imperilment, or even death. In this psalm, the unfathomable oceans signify the profound (but unspecified) sea of troubles from which the psalmist cries out to God.

Michael Arad and Peter Walker’s Reflecting Absence in Manhattan’s Memorial Plaza marks the absence of the Twin Towers, destroyed in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. It does so by siting two square voids on the footprints of the lost towers. Both of these vast and cavernous spaces (200 x 200 ft and 35 ft deep) are surrounded by dark polished walls of granite. On the lip of the walls are inscribed the names of those who died in the attacks, as well as those killed in the bombing of the towers in 1993: 2983 in total.

Down these walls, the water falls in thin veils to the pools at the bottom of each void, out of which the waters drain and disappear into two further square spaces (void within void, depth beneath depth)—as if vanishing into nothingness.

The two pools simply but, given their scale, very dramatically, represent what unfathomable depths of loss and despair are opened up by the experience of arbitrary and untimely death. From depths like these, and through seemingly unstanchable waterfalls of tears, human voices may find themselves in the psalmist’s company in reaching up toward the heavens.

The original design for the monument placed the pools in a bare, bleak, and vast plaza, but that scheme was modified at the instigation of the 9/11 Memorial Jury by the planting of a grid of some 400 trees. The addition of the trees, without detracting from the solemn statement made by the abysmal pools, places the absences they proclaim in a context of growth, renewal, and rebirth—for the voice of lament affirms life in the very act of mourning, even if it cannot presently find words of hope.

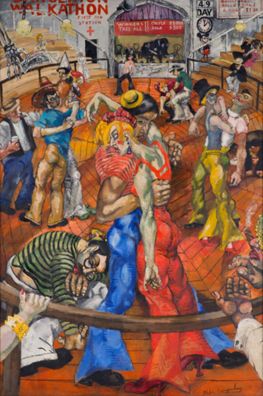

Philip Evergood

Dance Marathon, 1934, Oil on canvas, 52.6 x 101.7 cm, Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin; Gift of Mari and James A. Michener 1991, 1991.210, © Estate of Philip Evergood The University of Texas at Austin

Who Shall Stand?

Commentary by Michael Banner

The dance marathons of depression era America posed Psalm 130’s question ‘who could stand?’ (v.3) in a quite literal way. Competitors, tempted in their poverty by cash prizes—suggested here by the $1000 bill held out by a skeletal hand at the upper left of the picture—would sometimes dance for weeks on end, with whoever was left standing the winner.

The contest depicted here is in its forty-ninth day (so the sign to the right of the band declares), and surely its very final stages. The woman in red in the foreground is propped up by her partner, but is close to collapse, as are the other dancers. It is only a matter of time—and not very much time—before the last dancers collapse onto the floor with the others.

Conservative moralists criticized these dance marathons as encouraging illicit liaisons (Burns 2016: 117). But notwithstanding the skin-tight clothes of the participants, their exaggerated make-up and musculature, and their abandoned embraces, the picture suggests death throes more than the throes of passion.

The design of the floor that Philip Evergood shows us echoes the pattern of a spider’s web, and the painter seems as interested in drawing attention to those who have woven this web, as to those caught in it. In the left and right foreground (places where in a medieval or Renaissance painting we might find representations of a work’s donors), we catch a glimpse of two spectators. On the left, a woman’s hand, with its bright-red nail and a gaudy bangle at the wrist, grips the rail surrounding the arena, as she is presumably gripped by this display of suffering and degradation. To the right, a man with a fat cigar stuck in his mouth, and absurdly blonde hair, advances a podgy hand with stubby fingers—as if to receive a share of the proceeds.

But these witnesses of the scene do not, as in devotional pictures of the past, look on piously or pityingly at what is before them. Rather, they leer at a spectacle animated by that other and deathly hand holding out the $1000 bill, under whose presiding spell no one really stands.

References

Burns, Sarah L. 2016. ‘Death, Decay, and Dystopia: Painting the American Wasteland in the 1930s’, in America after the Fall: Painting in the 1930s, ed. by Judith A. Barter (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago), pp. 116–143

Martin, Carol J. 1994. Dance Marathons: Performing American Culture of the 1920s and 1930s (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi)

Rembrandt van Rijn

The Prodigal Son among the Swine, c.1650, Pen and brown ink, on paper, 159 x 235 mm, The British Museum, London; 1910,0212.179, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

At First Light

Commentary by Michael Banner

Rembrandt van Rijn treated the story of the prodigal son several times, imagining him at the beginning of the story carousing in a tavern with a harlot as ‘he squandered his property in loose living’ (Luke 15:13), and at the end, returning to his father’s forgiving embrace (Luke 15:20ff). In this drawing of c.1650, however, Rembrandt depicts him at the prodigal’s lowest point, which is also the story’s mid- and turning point.

The prodigal is down on his luck—on his knees, as we say, and here literally so. He has been reduced to caring for swine and is in such straitened circumstances that he would gladly share their food (Luke 15:16). The prodigal’s days as a riotous playboy are far behind him—he is boney and emaciated and, like an old man, seems to need his stick for support as much as for herding his charges. He is, however, so turned in on himself that he seems hardly to notice the pigs, lost in his thoughts as they are intent on their food.

With the greatest economy and delicacy, Rembrandt seems to have depicted the very moment when, from the depths of abjection, the possibility of forgiveness and so of hope dawns on the prodigal’s mind. On his knees, as if in prayer, he appears, hesitantly and tentatively, to entertain a thought like the psalmist’s: ‘there is forgiveness with thee’ (Psalm 130:4). We observe, perhaps, the very dawn of hope. But it is like the first signs seen by those who watch for the morning (v.6), no more than a glimmer—for hope, after all, need have no ground beyond the very barest intimation of possibility. We sense that the prodigal may rise from his knees.

Whether he will then be able to ‘stand’ (v.3) remains to be seen. From the depths, however, the prodigal, like the psalmist, has dreamt of forgiveness.

Michael Arad and Peter Walker :

Reflecting Absence, 2011 , Granite and bronze

Philip Evergood :

Dance Marathon, 1934 , Oil on canvas

Rembrandt van Rijn :

The Prodigal Son among the Swine, c.1650 , Pen and brown ink, on paper

From the Heart

Comparative commentary by Michael Banner

Each of Psalms 120–34 is headed ‘a song of ascents’. The significance of this liturgical marking, which dates from after the composition of the Psalms, is by no means clear, but a commonly favoured view is that these psalms were used by pilgrims as they climbed towards Jerusalem (Brueggemann and Bellinger 2014).

However that may be, Psalm 130 contains a sort of ascent within itself. The psalmist, who begins in the depths, and asks who shall stand if the Lord should mark iniquities, brings to mind that there is forgiveness with God, and so finds hope—which he then commends to his people:

O Israel, hope in the Lord!

For with the Lord there is steadfast love,

and with him is plenteous redemption.

And he will redeem Israel from all his iniquities. (Psalm 130:7–8)

Whatever may have been the original circumstance of this Psalm’s composition, its place in a group of psalms for pilgrims, as in the wider Psalter, allows its use as a script to guide and govern the life and times of others.

Even though in Philip Evergood’s painting, the dancers are all but asleep, they are not dreaming of redemption from the spider’s web of moral self-abasement in which they have been trapped. But the prodigal son of Luke 15 finds hope for forgiveness and redemption in a story that seems to make the Psalm’s thoughts his own. In Rembrandt van Rijn’s drawing, a delicate evocation of the great turning point in the story is shown, though—as in the Psalm—the hope the prodigal discovers has the tentative character which any hope for human forgiveness surely must.

The cri de coeur which opens the Psalm, ‘Out of the depths I cry to thee, O Lord’, has been voiced not only by those who cry out, as the prodigal did, from a place of moral self-despair. Indeed, it is by no means clear that the psalmist begins from such a place either. Though his despair may be on account of his moral abjection, on account of his ‘iniquities’ (Psalm 130:8), it need not be so understood—though the Psalm’s placing among the Seven Penitential Psalms as well as the Psalms of Ascent has favoured that interpretation. It could be that in the psalmist’s present calamity, whatever it is, he fears that his iniquities will prevent his supplications from finding a favourable hearing—that he will, in the words of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29, ‘trouble deaf heaven with my bootless [i.e. useless] cries’.

It is perhaps characteristic of public monuments to the tragedies of the last 100 years that they are, like Michael Arad and Peter Walker’s great pools in Manhattan’s Memorial Plaza, cries from the depths which are conceived as ‘troubling a deaf heaven’. They express a cry of pain but with no expectation that the cry will be divinely heard. The fear is not that the cry will go unheeded on account of the suppliant’s sins. Rather (human iniquity or not), it is that there is no divine ear ready to attend. Psalm 130 can be found on the wall of the Protestant chapel at Dachau—and in that place, as in most holocaust memorials, it is certainly not those whose cries went unanswered who are challenged to justify themselves.

Arad and Walker’s monumental depths do not however, preclude a sort of ascent, albeit one perhaps conceived even more tentatively than by the kneeling prodigal. It is again characteristic of the monuments of the late twentieth century that they expect and demand a hearing from us (just as the psalmist expects and demands a hearing from his people Israel), even if they express no faith that God is listening. The imperative which they issue is that we should remember, not necessarily as an end in itself, but for the sake of a better world in which ‘never again!’ We must attend to the cry of the victims of iniquity, and the plea for mercy which it expresses, lest history should repeat itself. Thus the trees which surround the monument come to symbolize a certain hope, if not for the victims here commemorated as such, then at least that their loss should not be a last word.

In its own way then, this monument to loss follows the ascent of the psalm, though by a different route from that taken by the prodigal. From the abysmal depths it does not utter what it takes to be a bootless cry, but one which it hopes will be heard and attended to by human ears. The monument, like the psalmist, patiently waits and watches—hoping against hope, perhaps, for ‘plenteous redemption’, even if human redeemers seem frail, few, and far between.

References

Brueggemann, Walter, and W. H. Bellinger. 2014. Psalms (New York: Cambridge University Press)

Commentaries by Michael Banner