Acts of the Apostles 7:51–8:3

The Stoning of Stephen

Vittore Carpaccio

The Stoning of St Stephen, 1520, Oil on canvas, 149 x 170 cm, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart; Acquired with the Barbini-Breganze Collection in 1852, no. 311, bpk Bildagentur / Staatsgalerie Stuttgart / Art Resource, NY

Incomprehension and the Seed of Faith

Commentary by Paul Hills

Vittore Carpaccio’s Stoning of Stephen is the final canvas in a narrative cycle of the saint’s life that was commissioned by the Scuola of Santo Stefano in Venice—a confraternity combining devotional, festive, and philanthropic functions.

In all the scenes, beginning with his consecration as deacon, Stephen is shown wearing his liturgical vestments. In the Stoning he kneels close to the right margin, vested in a dalmatic of red and gold over his white alb, with a maniple hanging from his wrist. Seen in its original location to the left of the altar, Stephen’s celestial vision would have appeared to hover above the altar where deacons assisted in the celebration of Mass for members of the confraternity.

Carpaccio sets the scene in a spacious landscape. Jerusalem on the hill to the left is shadowed by cloud, while sunlight bathes the upturned face of Stephen to the right. Turbaned figures process through the walls of the city towards the foreground, where Stephen’s audience is gathered. Carpaccio depicts them as varied in skin colour and costume. They turn towards each other, some perhaps enraged by Stephen’s earlier speech in which he had proclaimed Christ as the fulfilment of the Law and the Prophets (Acts 7:2–53), others by his declaration that he could see ‘the heavens opened, and the Son of man standing at the right hand of God’ (Acts 7:56). At the centre of the group the High Priest with long white beard looks on, stern and impassive.

Seated on the ground and hemmed in at the left corner, we discover the figure of Saul wearing the fancy scarlet hose and expensive tunic typical of the youthful patricians of Venice. Just like Stephen, he lifts his face towards the light and directs his gaze towards the same vision. A red mantle lies at his feet, and he raises a green one towards his beard. Together, Saul’s upturned face and mysteriously raised cloth suggest dawning enlightenment, albeit still mixed with incomprehension. A standing figure behind Saul, perhaps his alter ego, bears the large sword that will be the attribute of the Apostle Paul.

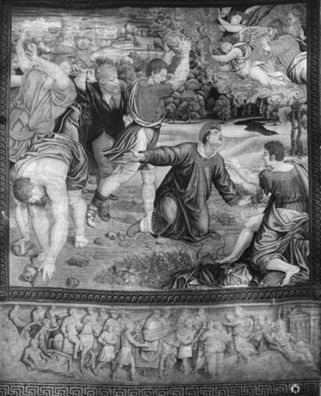

Workshop of Pieter van Aelst, from cartoon by Raphael

The Stoning of St Stephen, 1517–19, Tapestry, 450 x 370 cm, Musei Vaticani, Vatican City; MV_43871_0_0, Alinari / Art Resource, NY

The First Christian Martyrdom

Commentary by Paul Hills

The Stoning of Stephen, woven by Pieter van Aelst and his assistants after a cartoon (or full-scale drawing) by Raphael, belongs to a set of tapestries commissioned by Pope Leo X to hang on the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Installed on special feast days, these tapestries depict the stories of Saints Peter and Paul as related in the Acts of the Apostles. Bearing in mind this context, Raphael conceived the Stoning of Stephen primarily as the first scene in the story of Paul, rather than the last in the short ministry of Stephen.

In a packed composition of figures charged with physical energy, the angry audience of Stephen’s oration pick up stones ready to cast at him. The youthful saint has dropped to his knees in prayer and stretched wide his arms in a gesture of acceptance that recalls the outstretched arms of the Crucified Christ. Above, in the direction of the source of light, the martyr sees a vision of ‘the Son of man standing at the right hand of God’ (Acts 7:56). Here Christ, like Stephen, opens his arms in a wide embrace, and—in a significant detail—two angels part the clouds, one gazing back towards Christ and God the Father, the other looking down towards Saul seated below. The clothes of ‘the witnesses’ (see Acts 7:58) lie at Saul’s feet.

Beardless and still with a full head of hair, the young Saul responds to the youthful Stephen’s outstretched arms by reaching towards the martyr with open hands. His feet are bare and his left knee is bent in a pose almost like genuflection: as the site of the first Christian martyrdom this is sacred ground. In the next tapestry in the series, The Conversion of Saul, it is this future St Paul whose arms will be outstretched and raised towards Christ.

References

Lorenzo Lotto

Stoning of Saint Stephen (predella of the Martinengo Altarpiece), 1513–16, Oil on panel, 51.2 x 97.1 cm, Accademia Carrara di Bergamo Pinacoteca; 58AC00072, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Sharing the Passion of Christ

Commentary by Paul Hills

Lorenzo Lotto, a painter with a sharp eye for distinctions of dress, explores the significance of the Stoning of Stephen by contrasting clothed and naked figures.

On the right, the executioners act out a parody of the then recently discovered sculpture of the priest Laocoön and his sons, but unlike their classical models they are clothed. Lotto depicts Stephen kneeling on the ground, naked save for a red mantle, and behind him places a smartly dressed young man taunting the saint, a motif which recalls the stripping of Christ, the laying upon him of the scarlet robe, and his mocking (Matthew 27:28–30), and which reminds the viewer that Stephen in his martyrdom shares in the Passion of his Saviour.

A little behind the stoning itself, an elegant figure clad in tight-fitting hose, tunic, and hat of immaculate whiteness must be Saul, even though the clothes of ‘the witnesses’ that were laid at his feet are absent (see Acts 7:58). His cocky stance and prominent cod-piece are striking in the light of Paul’s later castigations of the sins of the flesh. His fashionable costume contrasts with the undress of the proto-martyr and the nudity of the soldier in the foreground, who whispers to his companion in armour. Such pictorial antitheses of foppish dress, nakedness, and armour may presage—not without a touch of irony on the artist’s part—Paul’s exhortations in his Epistles to ‘put on the whole armour of God’ (Ephesians 6:11; cf. Romans 13:11–14) as defence against sin and the devil. Since Lotto’s small panel belonged to the predella of an altarpiece commissioned by a soldier and painted in a period of almost incessant warfare in northern Italy, an allusion to Paul’s martial metaphor would have resonated with contemporary worshippers.

Today, when we are so often tempted to clothe ourselves with the vanity of worldly possessions, the painting may invite us to consider where true righteousness lies.

Vittore Carpaccio :

The Stoning of St Stephen, 1520 , Oil on canvas

Workshop of Pieter van Aelst, from cartoon by Raphael :

The Stoning of St Stephen, 1517–19 , Tapestry

Lorenzo Lotto :

Stoning of Saint Stephen (predella of the Martinengo Altarpiece), 1513–16 , Oil on panel

Turning towards the Light

Comparative commentary by Paul Hills

These three depictions of the Stoning of Stephen were all made within a span of about seven years. Raphael designed the Sistine tapestry in 1514, while in the same year Lorenzo Lotto was commissioned to paint the altarpiece with its predella, and Vittore Carpaccio was commissioned to paint his narrative cycle for the Scuola of St Stephen. He signed it in 1520. Yet despite their proximity in date, in all the images the relationship between the first Christian martyr and the future St Paul is depicted in meaningfully diverse ways.

In Lotto’s painting, Saul clearly ‘consents’ to Stephen’s death (see Acts 8:1). The scourge of the Christian community, vain and confident, this young man is still the antithesis of Paul. Lotto’s characterization of Stephen is equally distinctive. Instead of showing him in his deacon’s vestments, he emphasizes the parallels between his martyrdom and that of Christ. His nakedness here signifies virtue. The martyr raises his hands in the Western gesture of prayer rather than in the orant position more common in the Eastern Church. Saul and none of the other onlookers, including the lively dog, appear aware of Stephen’s vision, which is hidden within the clouds.

It is Raphael who brings Saul into the closest communion with Stephen. He also gives the greatest prominence to the vision of Christ and God the Father above, thereby preparing the viewer for the next scene represented in the tapestries, the dramatic Conversion of Saul, in which the flash of blinding light and voice from heaven knock the proud persecutor to the ground. Essentially, Raphael conceives the Stoning in terms of a conflict of the forces of good and evil expressed through the energy and emphatic gestures of his figures. Responding to the cacophony of voices mentioned in the text (Acts 7:57, 59), he turns up the volume to convey the rage and violence of Stephen’s assailants as they rush upon him shouting, and the saint’s response as he calls upon the Lord with a loud voice to forgive his enemies: ‘do not hold this sin against them’ (Acts 7:60).

Is it those words, Raphael’s image makes us wonder, that sow a seed in the hard heart of Saul and prompt him to stretch out his arms toward the martyr? No matter that the following chapter of Acts tells us that Saul ‘was ravaging the church’ (Acts 8:3) and became ever more ardent in his persecution of the Christians, for we have learnt to recognize that those in denial of their deepest feelings are often the most zealous and contrary.

In concentrating on the opposing forces of good and evil, Raphael glosses over many details in the account of Stephen’s martyrdom and the oration that provoked it. Like Raphael, Carpaccio envisages Saul’s witness of the stoning as a turn towards the light adumbrating his future conversion, but is more attentive to the backstory in picturing how the martyrdom unfolds. As an artist living in the cosmopolitan city of Venice, home to many foreign communities of merchants, entrepôt on the Silk Road, and point of embarkation for pilgrims to the Holy Land, Carpaccio was well equipped to respond to the Acts of the Apostles as canonical account of the spread of the Gospel to Jews and Gentiles alike. In his attention to the variety of racial types, the Venetian artist picks up on the passage in Acts 6:9 which relates that Stephen’s audience and accusers ‘belonged to the synagogue of the Freedmen … and of the Cyrenians, and of the Alexandrians, and those from Cilicia and Asia’.

Carpaccio was more skilled at depicting light as spiritual metaphor than showing figures in motion, and his Stoning of Stephen has been criticized for appearing static. Yet this sense of freeze-frame, of movement interrupted, suggests rather dramatically that several witnesses, like Saul himself, pause astonished by Stephen’s prayer asking the Lord to forgive them. Some of their number, like the Christian converts that Carpaccio encountered in Venice, turn towards the light; others turn away. Figures awkwardly turning become an effective metaphor for spiritual conversion or its rejection. By hinting at what is to unfold in Paul’s life and lead to his own martyrdom, Carpaccio’s painting involves us as active witnesses, and invites us to ponder our own response to Stephen’s imitation of Christ’s sacrifice.

With their contrasting interpretations of the narrative of the first Christian martyrdom, all three paintings suggest to the viewer that the path to the enlightenment of faith is always challenging and full of unexpected reversals.

Commentaries by Paul Hills