Proverbs 11

Straight and Crooked Paths to Wisdom

Hieronymus Bosch

Death and the Miser, c.1494, Oil on panel, 93 x 31 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC; Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1952.5.33, Photo: Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Filthy Lucre

Commentary by Deborah Lewer

Those who trust in their riches will wither. (Proverbs 11:28 NRSV)

Known as Death and the Miser, this painting by Hieronymus Bosch is both a didactic admonition for those who would lead a wise and good life and a dramatic allegory of the fate of the human soul after death.

A pale, naked old man is on his deathbed. No human companions tend him. Everything around him indicates that he has led a miserly and selfish life, hoarding money, possessions, and the attributes of status. The richly dressed man in the foreground is most likely to be a visual recollection of the miser in recent life. He is busily adding more gold coins to his demonic stash, his prominent rosary betraying his religious hypocrisy.

But now, Death is near, cadaverous in a grave shroud at the door. This is a moment of moral and spiritual urgency. Will Proverbs’ warning that ‘riches do not profit in the day of wrath’ (11:4) be heeded?

There is hope. A white-robed angel has come to the old miser, urging him at last to look upwards, to the light of Christ on the cross at the upper window—the source of salvation.

The worried expression on the angel’s face as he notices a scaly demon atop the bedhead says it all, however. Even with the fate of his soul at stake, the miser is tempted by the bulging bag of money offered by another ugly little demon, and reaches out for it. Death’s arrow is aimed directly at the man’s grasping hand and lower body; the light of his potential salvation, is, by contrast, aimed straight at his heart.

This panel was originally part of a triptych dealing largely with the congenital condition of human folly. Technical examination has revealed its connection to other surviving panels, though there is no firm consensus about what the subject of the triptych’s probably more explicitly religious central panel may have been. Seen in the light of Proverbs 11, Bosch’s miser reminds us that ‘the wicked earn no real gain’ (v.18). His own fate hangs on whether he can yet recognize the empty nature of riches over the everlasting ‘fruit of the righteous’ (v.30).

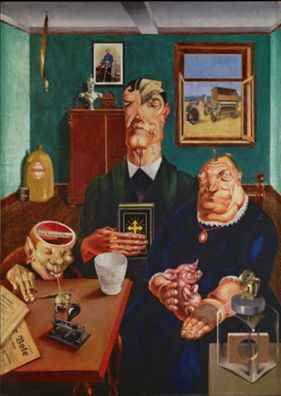

Georg Scholz

Industrialised Peasants (Industriebauern), 1920, Painting and collage on plywood, 98 x 70 cm, Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal; Photo: akg-images / Erich Lessing

Those Who Have

Commentary by Deborah Lewer

The people curse those who hold back grain. (Proverbs 11:26 NRSV)

Georg Scholz’s Industrialised Peasants is one of the most caustic images of the German Weimar Republic. It was first shown in post-war Berlin: at the First International Dada Fair of 1920. Scholz made this work using paint with collage and photographic fragments. The montage technique is characteristic of the Dadaists’ means of encouraging a more critically engaged way of seeing.

These ‘industrialized peasants’ are a farming family. They live surrounded by the trappings of patriotism and bourgeois respectability. A bust of the abdicated Kaiser is visible near a photograph of, perhaps, a son, in military uniform. The father dominates the group, stiffly clutching a gilt-edged hymnbook with a prominent cross, while two paper money fragments show what is really on his mind. A conservative Christian newspaper can be glimpsed on the table. A mother, or grandmother, stares vacantly, clutching a fat piglet to her own porcine body. The child at the table is Scholz’s most grotesque creation, his head hollow and his expression sadistic as he tortures a toad he traps with bony fingers.

Outside is a large modern threshing machine, ready for a big harvest. A fat sack of grain with a marked weight by it stands in the corner, suggesting a hoard and a concern with weights and measures, as doubtful as the evident morality of this crooked family. They resemble the cruel and the godless in Proverbs 11: people who hoard riches and deal in ‘false balances’ (v.1).

Over the course of the war of 1914–18, black market prices for various grains rose from the ‘official’ pre-war price by 2,000–3,000% (Blum 2013: 1070). By 1920, people were suffering the long-term effects of rationing, shortages, and malnutrition.

Scholz related this scathing artwork to his own experience. He claimed that, as a wounded veteran in 1919, he once asked some wealthy farmers for some food to feed his family, but was offered only their compost heap (Doherty 2006: 92). The uncompromising details of Industriebauern express the artist’s own verdict on the wicked’s withholding of ‘what is due’ (Proverbs 11:24).

References

Blum, Matthias. 2013. ‘War, Food rationing, and Socioeconomic Inequality in Germany During the First World War’, The Economic History Review, 66.4: 1063–83

Doherty, Brigid. 2006. ‘Berlin’, in Dada, ed. by Leah Dickerman (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art), pp. 87–153

Richard Long

A Line Made by Walking, 1967, Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper and graphite on board, 375 x 324 mm, Tate; Purchased 1976, P07149, © 2019 Richard Long. All Rights Reserved, DACS, London / ARS, NY; Photo: © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Straight and True

Commentary by Deborah Lewer

The righteousness of the blameless keeps his way straight. (Proverbs 11:26 NRSV)

Richard Long was still a sculpture student at St Martin’s School of Art in London when he made A Line Made by Walking in 1967. A deceptively modest work, it is now recognized as seminal, both for his own oeuvre in what would be a long career, and for the history of post-war sculpture, conceptual art, minimalism, and land art.

A Line Made by Walking works in more than one temporal register. It is a photographic trace of a brief, time-bound, live action by one man on one summer’s day in 1967. The image shows an ordinary field in the southwest of England, and a straight line ahead over the field. It was made by Long walking back and forth, repeatedly, wearing down the grass to impress a light, linear marking on the earth. It is also a lasting material record of that action’s imprint on the land, in the form of a photograph, printed together with an inscription on the mount below, which reads: ‘A LINE MADE BY WALKING. ENGLAND 1967’.

Long is one of the first generation of artists who worked using nature and documentary methods in this way in the late 1960s, mediating between the outdoors and the gallery. The work tended to be unobtrusive and ephemeral, before more monumental earthworks began to be made, particularly by American land artists.

In its simplicity, clarity, modesty, and harmony with nature, A Line Made by Walking also offers some suggestive parallels with the qualities of virtue praised in Proverbs: accuracy; the ‘uprightness’ that ensures one’s way is not crooked (11:3, 11); the ‘righteousness of the blameless’ that ‘keeps their ways straight’ (11:5).

Long has since undertaken many long-distance walks, across the world. He says:

I am interested in … the universal similarities between things, but also in the great differences between places, because each place on earth is absolutely unique. (Long and Cork 1991: 249–50)

Footpaths especially interest him in this context because the walking of pathways is a universal part of human experience and yet paths are always specific. Like the paths of virtue commended in the book of Proverbs, every path, ‘no matter where it is’ is at the same time ‘one footstep after another’ (Long and Cork 1991: 249–50).

References

Long, Richard and Richard Cork. 1991 [1988]. ‘An Interview with Richard Long by Richard Cork’, in Richard Long: Walking in Circles (London: Thames and Hudson), pp. 248–52

Hieronymus Bosch :

Death and the Miser, c.1494 , Oil on panel

Georg Scholz :

Industrialised Peasants (Industriebauern), 1920 , Painting and collage on plywood

Richard Long :

A Line Made by Walking, 1967 , Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper and graphite on board

Misers and Measures

Comparative commentary by Deborah Lewer

Proverbs 11 is part of the oldest collection of proverbs in the book (10:1–22:16). It opens with a statement about the righteousness of true and accurate measures: YHWH abhors a ‘false balance’ and delights in ‘an accurate weight’ (11:1). Balance, uprightness, constancy, steadfastness, and diligence are characteristic of the ordered worldview of the proverbs. When their equilibrium is upset—by wickedness, crookedness, cruelty, avarice, folly, and violence—the ensuing consequences are both just and inevitable.

As much as anything else, wisdom consists here in practical understanding about how to live a good life.

Many of the didactic contrasts between the ‘righteous’ and the ‘wicked’ in Proverbs 11 (as elsewhere in the book) address the themes of wealth and poverty that confronted viewers of Hieronymus Bosch’s panel, Death and the Miser. The painting emphasizes Christ as the way to salvation. In Proverbs, it is a judicious, and ‘blameless’ life wisely led that leads to flourishing, and that is YHWH's ‘delight’ (11:20). In both visions, justice and accountability prevail. The miser on his deathbed will—so it is implied—‘wither’, having ‘trusted in his riches’ (11:28). He risks an afterlife, not of flourishing, but of depletion, material and spiritual.

Closer to our own time, but with distinctly Boschian echoes, Georg Scholz also takes us into the intimate sphere of domesticity to expose, ruthlessly, the inhabitants’ moral lives. The aftermath of Germany’s defeat in the war of 1914–18, the collapse of the German empire, and the precarious beginnings of a new Republic were marked by poverty, severe shortages, conflict, and deep resentments. Scholz’s Dadaist work, Industrialised Peasants, indicts those profiteering German farmers who ‘held back grain’ (11:26), causing inflated prices and devastating hunger to their fellow people. In the phrasing of Proverbs 11:26, the artist ‘curses’ them and their hoarding miserliness, represented by the cossetted piglet, the sack of grain in the corner of the room, and the expensive new farm machinery outside. He presents them as a family of sadistic and grotesque hypocrites, even their snot-nosed offspring ‘looking like a monster displaced from a painting by Hieronymus Bosch’ (Doherty 2006: 92). Their piety—with the prominent hymnbook and Christian newspaper functioning like the miser’s rosary in Bosch’s work—is revealed as a meaningless veneer for merciless avarice.

Verses 11:24–26 of Proverbs all deal with meanness and generosity, critical contrasts between two kinds of people and between two ways of living. Those who give freely are blessed, metaphorically ‘watered’, and they ‘grow richer’. Their gain is an abundance of blessing on their lives and bodies. On the other hand, those who ‘withhold what is due’ (11:24) will suffer. Their spiritual deprivation echoes the material deprivation they inflict on others. The culmination of this group of proverbs is verse 26, which presents the tangible example of miserliness: holding back grain.

So, what wisdom does Proverbs 11 offer for a good life, pleasing to God? Richard Long’s early work, A Line Made by Walking is most commonly read as a challenge to conventional understandings of sculpture or as a subtly provocative intervention in the British landscape tradition in art. Seen in juxtaposition with some of the words of guidance and admonition in Proverbs 11, Long’s work takes on new connotations. It suggests straight paths that are habitual, walked consistently, and an upright gait (11:3, 6, 11). Without reading the parallel too literally, Long’s modest and benign intervention in the landscape, his own way of moving and being within it, might sharpen our attention to how the didactic language of Proverbs consistently conjoins bodily and moral rectitude.

Living well means developing the wisdom that is ‘with the humble’ (11:2). It means steadfast ‘upright’ habits that become so ingrained as to be innate and natural. Together, these three works of art, from periods of both promise and strife in the history of Europe, open up some vivid dimensions of this universal guidance for the human paths to wisdom and righteousness.

References

Doherty, Brigid. 2006. ‘Berlin’, in Dada, ed. by Leah Dickerman (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art), pp. 87–153

Commentaries by Deborah Lewer