Deuteronomy 4:44–5:33

Love Commandments

Gustave Moreau

Head of Moses (Study in connection with Moses, in View of the Promised Land, Takes off his Sandals), c.1854, Lead pencil, white chalk on laminated tracing paper, 326 x 235 mm, Musée national Gustave Moreau, Paris; 2202, René-Gabriel Ojéda © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Second Law

Commentary by Casey Strine

It is striking that the Ten Commandments in Deuteronomy 5 are not the earliest version of this text, but a repetition of Exodus 20. Deuteronomy highlights this, presenting itself as Moses’s words to the second generation of the exodus just before they cross the Jordan River into the promised land. Even the book’s name recalls the fact: it comes from the Greek words deutero (second) and nomos (law). It is the repetition of the law.

Gustave Moreau’s study for the head of Moses also depends on a prior representation of its subject: Michelangelo’s famous sculpture of Moses on the tomb of Pope Julius II in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome. Yet, while depending on the sculpture, Moreau also makes the subject his own.

Moreau’s Moses appears less severe than Michelangelo’s. He is somehow a gentler figure. His beard is not a torrent of tight coils, and we see unkempt hair in place of his infamous horns. This Moses looks more like an elderly academic. And yet his eyes remain piercing, so that Moreau retains the sense that Moses could see through you, perhaps into a deeper dimension of reality.

So too with Deuteronomy: it is not a slavish repetition of Exodus. Deuteronomy repeats the command to celebrate the Sabbath—the day of rest Jews practice on Saturdays—but changes the rationale from God’s rest in creation (Exodus 20:11) to the memory of the slavery in Egypt. This is a precursor of what is to come in Deuteronomy 12–26, in which all manner of instructions from Exodus are reshaped.

Why is this important? It highlights that the Bible is not a flat, static text, but contains within its contents evidence that ideas and practices are alive. Israel’s ideas grow and transform; they adapt to new times and places. Theology and religious practice have never been static, but since the very origins of the Jewish and Christian traditions they have been living, malleable things.

In this respect, they resemble iconic figures depicted in ever-new and fresh ways by generations of artists as they work in ever-changing contexts.

Tracey Emin

I Fell in Love Here, 23 Feb 2014, Neon, 22.9 x 160 cm, Location currently unknown; © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved DACS / Artimage, London and ARS, NY 2018. Image courtesy Lehmann Maupin

How Shall We Respond?

Commentary by Casey Strine

Laws. Rules. Prohibitions. Those are the things a contemporary audience might think of when they hear the Ten Commandments. For such an audience the text speaks only of what one must do and what one must not do. Here, it seems, is a preeminent example of God as a rule-maker and an uncompromising arbiter of proper conduct.

Yet, within the framework of Deuteronomy, the Ten Commandments generate love from their audience, the Israelites who are preparing to enter the ‘promised land’. In the following chapter, those who hear these instructions encourage one another in words that Jews call the Shema: ‘Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD; and you shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might’ (Deuteronomy 6:4–5). The Ten Commandments are not the prelude to judgement. Instead, the place where the people of God hear the Ten Commandments becomes the spot they recall falling in love with God.

All this resembles the vows between two people at a wedding ceremony. One might hear marriage vows as a list of things one must and must not do. One might. That is hardly the correct way to interpret those words. It is certainly not what they intend to express or to produce in response. Marriage vows are at best a deep and heartfelt expression of an enduring and precious love for another person, even if phrased in formal, legalistic words. No ‘I will’ should ever arise without the exclamation ‘I fell in love here’ preceding it.

Likewise, the Ten Commandments are formulaic statements, but ones that express God’s love for God’s people. They give outward and generalizable form to a relationship that is inwardly and personally aflame (as Emin’s words are both shareable by others and yet reproduce her own unique handwriting). The Commandments’ words provoke the people of God to declare their love for God in response, and shape that declaration into a way of life. They provide a way to love God back. This is why the Shema has served as the central confession of Judaism and why Jesus taught it to his followers as the ‘greatest commandment’ (Matthew 22:36–38).

Out of the Midst of the Fire

Commentary by Casey Strine

Deuteronomy 5 starts by saying that God spoke to the people of Israel ‘out of the midst of the fire’: an image that is, by design, hard to imagine. Fire represents the glory, the power, and the danger that accompany the presence of God. The people are in awe, and afraid. Their fear keeps them from approaching God.

Tracey Emin’s use of neon helps to unfold this experience. From a distance, neon signs are luminous, attractive, and in this case, the means of transmitting a pleasing message. Those who have fallen in love can often remember the precise place it happened. Those experiences may retain a warm glow in the memory. Sometimes people revisit those places, for they possess a sacred quality that grants the memory an almost tangible presence, that transports one through time to where love began.

But, when one gets close to a neon sign there is usually an incessant buzzing, like an insect zapper. How stable is the contraption, one wonders? Neon signs—the product of trapping neon gas in a glass tube and then stimulating it with electric current—are somehow disconcerting when one is right next to them.

And so it is with the deity that Israel encounters ‘face to face’ (Deuteronomy 5:4). If luminous, warm, and comforting from a distance, this deity produces unease when nearby. Israel deduces the need for a specialist, someone who knows how to deal with this smouldering presence. They plead with Moses to be their mediator. He will speak with God on their behalf, so that they might not die, while also not being cut off from the life-giving voice of God, whose love they crave.

Pablo Picasso

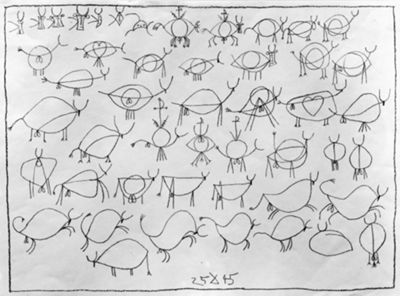

Sketch with bulls, 1946, Pen and ink, 210 x 350 mm, Private Collection, France; © Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artist's Rights Society (ARS), New York Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Litany of Life

Commentary by Casey Strine

Pablo Picasso demonstrated virtuosic skill in rendering the form of a bull multiple times through an economy of means—simple line drawings. On this sheet the image of the bull is highly simplified and viewed from every angle. Picasso’s studies demonstrate that these line drawings were carefully considered, painstakingly conceptualized, precise expressions of his thoughts.

Picasso cannot express his reflections on the bull—a subject that enthralled him for decades—in a single drawing. His ideas compel him to create a complex and diversified series. Likewise, God’s outline of the proper nature of divine–human and human–human relationships cannot be accomplished in one statement. It is important to note in this regard that the Ten Commandments are themselves a summary of the hundreds of specific statements about legal cases and the problematic situations of human interaction found in chapters 12–26 of Deuteronomy. And yet, even the Ten Commandments are further distilled into a single statement, with Deuteronomy 6:4–5 encapsulating all of God’s instructions in the call to ‘love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might’.

Or, is it the other way around? In order to truly understand what constitutes a love that engages all of one’s mind, soul, and strength, must one take the time to expound its various dimensions? Perhaps one should read the Ten Commandments not as a convenient, memorable summary of the all too cumbersome legal material modern readers avoid in Deuteronomy 12–26, but as the first necessary step in an essential process whereby the outline form of love for God is joyfully, pleasantly, and affectionately given the complexity and texture of application into a litany of life situations.

Picasso remained fascinated with the bull throughout his career. It was an inexhaustible topic for him, which required a bounty of artistic responses in an attempt to capture a central idea. The Ten Commandments, and the other texts connected to them, suggest that the love of God will require equally sustained consideration and response.

References

Daix, Pierre. 1993. Picasso: Life and Art, trans. by Olivia Emmet (London: Thames and Hudson)

Richardson, John. 2009. A Life of Picasso, New Edition, 3 vols (London: Pimlico)

———. 2017. Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors (London: Rizzoli International Publications)

Idol Sketches

Commentary by Casey Strine

The bull, the subject of this study by Pablo Picasso, hovers over the second commandment: ‘You shall not make for yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth’ (Deuteronomy 5:8). This command prohibits a practice that was not just common in the world of ancient Israel, but the absolute norm in ancient worship. Often called idols, finely crafted statues representing a goddess or god filled the temples and shrines of the ancient world.

By contrast, the authors of Deuteronomy rejected this norm, and this rejection was a crucial element of what would identify Israel as a unique community. Israel was to demonstrate its allegiance to its God by rejecting other deities (the first commandment, Deuteronomy 5:6–7) and by declining to adopt the dominant mode of engaging with those gods: worshipping a statue.

Israel would fail miserably. The story of the golden calf is well known: while the people wait for Moses to return from the top of Mount Sinai with more of God’s words, they tire of the delay, and they ask Aaron, Moses’s brother and lieutenant, to make them a statue to worship. Offering up their own jewellery as raw materials, they watch as Aaron produces a golden calf: their rejection of God takes the physical form of a young bull (Deuteronomy 9:8–21; Exodus 32).

Creatively adapted, Picasso’s images of the bull can help us to reflect on the second commandment and successive human responses to it. His diverse depictions of the bull can be read in a way that recalls the myriad ways that the people of God have expressed their disobedience.

No two people love in the same way, nor do they rebel in the same way. Ever was it so.

Gustave Moreau :

Head of Moses (Study in connection with Moses, in View of the Promised Land, Takes off his Sandals), c.1854 , Lead pencil, white chalk on laminated tracing paper

Tracey Emin :

I Fell in Love Here, 23 Feb 2014 , Neon

Pablo Picasso :

Sketch with bulls, 1946 , Pen and ink

No Place for Complacency

Comparative commentary by Casey Strine

God’s instructions for humans are both simple and complex, both straightforward and multilayered. Tracey Emin prompts us to consider the many layers of meaning that may attend a simple phrase. So, too, Pablo Picasso’s line drawings of bulls have a crisp elegance even while one knows they are the expression (and the product) of a multiplicity of experiments in depicting his subject.

Neither work is facile. What does it mean to fall in love? And what makes the place where it happened so special? Emin poses questions with her work that reward sustained reflection. Meanwhile Pablo Picasso’s sketches have a simplicity and clarity born of diligent work and painstaking analysis of the subject.

Analogously, the statements in the Ten Commandments are immediately transparent while also pregnant with layers of meaning. It might take a lifetime, for example, to discover the implications of ‘honour thy father and thy mother’. So, too, the prohibitions against murder, lying, adultery, theft, and covetousness are all indexed to an infinitely-modulated world of human reciprocity.

All the more so God’s declaration that ‘I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery; you shall have no other gods before me’ (Deuteronomy 5:6). In arresting, staccato statements, God confronts us with what it takes to have strong, loving relationships. A stripping away of the idols of our own making, in favour of the absolute truth of God, stands as the necessary condition of such flourishing.

And yet, God’s face is nowhere to be seen in this passage. In a book that depicts both a deity capable of parting the seas and also a people who will conquer a multitude, a single man emerges as the central figure. Deuteronomy 5 cements his centrality. Just as Moses’s head is the only thing in Gustave Moreau’s sketch, so God does nothing in Deuteronomy without his chosen servant. God’s speech is simultaneously Moses’s words. The entire text emerges from Moses’s mouth, in a series of three speeches. He stands ‘to declare … the words of the LORD; for you were afraid because of the fire’ (Deuteronomy 5:5). Moses embodies God’s thoughts, words, and power in human form. He operates as the source of all wise instruction and the judge of all that is just.

We too may see the divine only in the other human beings with whom we are in relationship. Moreau’s Moses reminds us that the human face may be that vehicle through which we encounter God most intensely. Indeed, Moses’s concentrated gaze in Moreau’s sketch evokes the God of Deuteronomy, whose character is made manifest in both compassion and unyielding intensity.

The compassion that Deuteronomy proclaims is that of a God who saves people from bondage; it depicts a deity who commands people to rest each week, despite all that need be done, so they never forget that liberating act of compassion; it teaches about the LORD who desires that ‘you may live, and that it may go well with you, and that you may live long in the land’ (Deuteronomy 5:33).

But beware! Complacency has no place here. ‘You must therefore be careful to do as the LORD your God has commanded you; you shall not turn to the right or to the left. You must follow exactly the path that the LORD your God has commanded you, so that you may live, and that it may go well with you’ (Deuteronomy 5:32–33). The compassionate God remains prepared to judge disloyalty; he has a power greater than the fiercest strength of any bull, and requires faithfulness to his instructions. The eyes of Moreau’s Moses may remind us of how the divine gaze penetrates our external façades and of how this God perceives what rebellion lurks inside us.

Emin’s neon remains an apt representation of the apparent tensions in humanity’s relationship with God envisioned by Deuteronomy 5. God’s love for his people glows warm and bright, ready to meet them in the place they stand, wherever that is. But to experience this love, one must accept a risk—that God’s fierce determination to make us fit for such relationship might, like the electric current in the neon tube, cause us pain.

![Head of Moses [Study in connection with Moses, in View of the Promised Land, Takes off his Sandals] by Gustave Moreau](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/B77_Gustave+Moreau%2C+Head+of+Moses_ART560671_cropped.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Casey Strine