Matthew 2:16–18

The Massacre of the Innocents

Works of art by Nicolas Poussin, Unknown artist and Unknown Byzantine artist [Rome or Milan]

Unknown artist

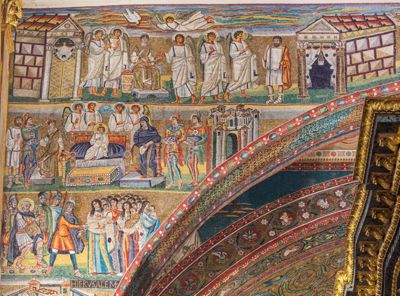

Massacre of the Innocents, mosaic on the triumphal arch of the nave, 5th century, Mosaic, Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome; Ivan Vdovin / Alamy Stock Photo

‘Flee from the wrath to come’

Commentary by Robin Jensen

Shortly after the Council of Ephesus formally awarded the title Theotokos (Mother of God) to the Virgin Mary, Pope Sixtus III (432–40 CE) commissioned a church in Rome to her, Santa Maria Maggiore. Today its fifth-century mosaic programme remains one of the oldest in the world and includes a cycle of nave mosaics showing scenes from the Old Testament books of Genesis and Exodus and a triumphal arch that displays episodes from the infancy of Christ according to both Matthew and Luke: the Annunciation, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Adoration of the Magi, the Flight to Egypt, and the Presentation in the Temple.

The image of the Massacre of the Innocents appears in the spandrel at the lower left side of this mosaic, just below the scene of the Adoration of the Magi and directly across the arch from a depiction of the Magi appearing before King Herod. Here Herod, on the left, sits on a gold and gem-studded throne and is surrounded by his bodyguards. He is dressed in Roman military garb and he has a halo indicating power and authority. He looks directly at one of the guards and gestures as if commanding him to remove a child from his mother’s arms. At the right, a crowd of other women holding their children close to them include one mother turning away as if to flee with her child. She may have been intended to be identified as Elizabeth with the infant John the Baptist.

This image differs from most other renderings of the story in its omission of the violent act of child-murder. The soldier who reaches to take the child from its mother’s arms glances back at Herod as if anxious to hear the order rescinded. The mothers grasping their children to their bosoms appear not to understand what is about to happen. Only one turns away.

References

Kötzsche-Breitenbruck, Lieselotte. 1968–69. ‘Zur Ikonographie des bethelemitischen Kindermordes in der frühchristlichen Kunst’, Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum, 11–12: 104–15

Unknown Byzantine artist [Rome or Milan]

Relief panel with scenes from the life of Christ (Massacre of the Innocents; Baptism of Christ; Marriage at Cana), First third of 5th century CE, Ivory, 20 x 8.1 x 0.8 cm, Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Bode-Museum, Berlin; Inv. no. 2719, bpk Bildagentur /Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Bode-Museum, Berlin / Art Resource, NY

‘As you did it to one of the least’

Commentary by Robin Jensen

One of the oldest surviving depictions of the Massacre of the Innocents (Matthew 2:16–18) appears at the top of this early fifth-century carved ivory relief panel. The panel was one of a hinged pair (diptych) whose other half now resides in Paris’s Musée du Louvre.

The Berlin panel is divided into three sections. Below the massacre scene are images of Christ’s baptism by John and the Cana miracle in which Jesus transforms water to wine (John 2:1–11). The Louvre panel also has three sections, but in this half of the diptych it is episodes of Christ healing that are portrayed: the woman with the issue of blood, the paralytic, and the Gerasene demoniac.

In the Massacre, the unknown artist has depicted King Herod at the right—slightly larger than life. He is enthroned in a high-backed chair with his feet resting upon a footstool. Herod’s gesture indicates that the violent act we witness is by his order. At the centre, an unarmed Roman soldier grasps a naked baby by the leg and swings it over his head in order to hurl the child to the ground. Another child lies dead at Herod’s feet. Behind the soldier, two distraught mothers express their horror and grief; one raises her hands in lament.

The work is exquisitely executed. The violent scene seems almost to be redeemed by the beauty of the figures’ modelling and the artist’s skilful composition. Yet, the choice of this particular scene here may puzzle those who expect to see the more commonly depicted and uplifting images of Christ’s Nativity or the Adoration of the Magi in place of this distressing episode.

In fact, scenes of violence and torture are highly unusual in early Christian art. Extant representations even of Christ’s crucifixion are extremely rare before the sixth century.

However, the baby about to be slaughtered looks much like the childlike, nude Jesus being baptized in the scene just below and the similarity may be intentional. Perhaps the artist intended the image to allude to Christ’s execution—an event in which another King Herod is complicit. This little child is perhaps the first Christian martyr. His death will soon be followed by John the Baptist’s and then, of course, by Christ’s.

References

Effenberger, Arne and Severin, Hans-Georg. 1992. Das Museum für spätantike und byzantinische Kunst (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) #49, 135–36

Nicolas Poussin

The Massacre of the Innocents, c.1628–29, Oil on canvas, 147 x 171 cm, Le musée Condé, Chantilly, France; PE 305, Photo: Michel Urtado © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Tragedy and Nobility

Commentary by Robin Jensen

The date of this painting by Nicolas Poussin is disputed, but most historians allow that it dates to the years between 1632 and 1637 and was probably inspired by the publication of Poussin’s friend Giovanni Battista Marino’s epic-length poem, La Strage degli Innocenti (The Slaughter of the Innocents), published posthumously in 1632.

Marino’s poem is regarded as an outstanding example of how a horrific scene may be described in exquisite verse. Poussin similarly renders this ghastly event with almost classicizing beauty. Here Herod is absent and the setting appears to be the courtyard of a classical temple with a pyramid rising behind it.

The highly-reduced composition consists of only a few figures, with the three main characters depicted in a dramatic triangular arrangement. A bare-chested soldier with his foot upon a baby’s throat is raising his sword to slaughter him. With his left hand he grasps the hair of the desperate mother, who is pleading for her child’s life and trying to shield him with her own body. The soldier’s face and chest are shadowed. Instead the light strikes the mother’s face and outstretched arm along with the baby’s body. The woman’s open left hand reprises the flailing hands of the wailing baby. Another grief-stricken woman runs off to the right. Her face upturned, she appears to be shrieking in terror. In the background are three other female figures; one looks over her shoulder at the scene, one hides her eyes, the third may be making an escape.

Despite the suggestion of distant landscape, the action takes place in a shallow space, making the viewer observe it up close and as if seen from slightly below. And although the composition expresses a kind of sculptural stillness, as if frozen in time, the artist has also managed to express frenzied movement. The terrifying act and the pathos of the two women, delineated in lush colours and skilled rendering, achieve the combination attributed to the poet Marino: a juxtaposition of the horrific with the beautiful; tragedy and nobility.

References

Cropper, Elizabeth and Charles Dempsey. 1996. Nicolas Poussin: Friendship and the Love of Painting (Princeton: Princeton University Press), pp. 253–78

Unknown artist :

Massacre of the Innocents, mosaic on the triumphal arch of the nave, 5th century , Mosaic

Unknown Byzantine artist [Rome or Milan] :

Relief panel with scenes from the life of Christ (Massacre of the Innocents; Baptism of Christ; Marriage at Cana), First third of 5th century CE , Ivory

Nicolas Poussin :

The Massacre of the Innocents, c.1628–29 , Oil on canvas

An Unequal Struggle

Comparative commentary by Robin Jensen

The Massacre of the Innocents, an episode found in Matthew’s infancy narrative (2:16–18), became a frequent subject for Christian preachers, poets, and artists around the late fourth century and into the modern period. The story also appealed to artists through the centuries.

It features a despotic ruler, Herod the Great, who—fearing that his rule may be threatened—orders the slaughter of all children born in Bethlehem in the prior two years. Thus, the tale centres on the evil acts of a paranoid ruler and the anguished parents whose innocent children are sacrificed to his wicked obsession. It is also thematically connected to the exodus story of the Passover (Exodus 12–14), and prompts the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt (Matthew 2:13–15).

Although Matthew’s Gospel is the only New Testament source for the episode, it appears also in the apocryphal Protevangelium of James (22), which adds that when Elizabeth heard that Herod was seeking to kill the children, she fled with her son John and found shelter in a miraculously opened mountain crag. This detail may have been incorporated into the fifth-century mosaic panel in Rome’s Santa Maria Maggiore and perhaps also in Nicolas Poussin’s seventeenth-century painting.

Comparing the literary treatment of the Massacre alongside its visual depictions accords an analysis of the differences between verbal and visual renderings of a famous story. One of the earliest textual treatments comes from the work of the Christian poet Prudentius (c.348–413 CE) born in the Roman province of Tarraconensis (now Northern Spain). In a hymn dedicated to the Feast of the Epiphany, the poet recounts the story of the Holy Innocents and describes Herod ordering his sword-wielding soldiers to steep cradles in blood and stain mothers’ breasts with the blood of their children.

A second early text, a sermon of Basil of Seleucia (c.450 CE), was widely known throughout antiquity and into the early modern era. Here the preacher imagines himself as a spectator of the event. Focusing his attention on the guards’ violence and the mothers’ terror, he frames the tale as a battle between frantic women and vicious men. Herod is cast as an evil commander who urges his soldiers to terrible acts. Weeping mothers search out the scattered and broken bodies of their infants, kissing them and mixing tears and milky breasts with blood and brains.

Other literary treatments of the story include a sixth-century kontakion of Romanos the Melodos, an eighth-century homily by John of Euboea, and the famous seventeenth-century poem by Giovanni Battista Marino, La Strage degli Innocenti (The Slaughter of the Innocents). Historians generally agree all these different literary works influenced the visual representation of the story of the Massacre, although details sometimes do not align. For example, in the Berlin ivory, the soldier throws the child down on the ground, rather than using a sword, as in Prudentius’s poem. This detail, however, appears in the later work of Marino, who describes an infant being swung around and hurled against a wall before being struck by the blade. By contrast, Basil’s sermon describes Herod’s throne as golden and gem-studded, a detail that appears on the Santa Maria Maggiore mosaic. This raises the long-standing question of whether the influence of texts and images on each other is always one way.

Later artistic renderings than the ivory and the mosaic in this exhibition include a detail in the Syriac Rabbula (or Rabula) Gospels (c.586 CE), an eleventh-century icon at the Monastery of St Catherine in Sinai, and part of the fourteenth-century mosaics at Constantinople’s Chora Monastery (Kariye Camii). The Chora image includes the scene of Elizabeth’s escape with the infant John, as the Santa Maria Maggiore mosaic seems also to do.

As evident by the striking differences between the Berlin ivory and the Santa Maria Maggiore mosaic (which appeared around the same time), artists imaginatively elaborated the brief story in the Gospel in order to create a fully realized composition. Whether they chose either to emphasize the horror of the story or to downplay it may be due to the context or setting of the work or the artist’s intent. This is particularly true of Poussin’s composition. While Poussin was almost certainly influenced by Marino’s poem, he did not feel obliged to follow it slavishly. Nevertheless, his painting exemplified Marino’s aim to present a horrific scene with superb beauty.

Notwithstanding the variety in visual interpretations of this episode, Herod has remained constant as a paradigm of the paranoid despot. Meanwhile his massacred children are commemorated as the Holy Innocents and the first martyrs for the faith. In the words of Augustine of Hippo, ‘when the lion of heaven was born, the little fox of the earth was troubled … A divine infant came, and infants went to God’ (Sermon 375).

References

Cropper, Elizabeth. 1991. ‘The Petrifying Art: Marino's Poetry and Caravaggio’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, 26: 193–212

———. and Charles Dempsey. 1996. Nicolas Poussin: Friendship and the Love of Painting (Princeton: Princeton University Press), pp. 253–78

Fogliadini, Emanuela. 2019. ‘The Massacre of Innocents: Representing the Biblical Suffering in the Mosaics of Chora’, Ikon: Journal of Iconographic Studies, 12: 19-28

Maguire, Henry. 1996. Art and Eloquence in Byzantium (Princeton: Princeton University Press) pp. 25–34, 118–21

Rotelle, John E. (ed.), Edmund Hill (trans.). 1995. The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century, III/10, Sermons 341-400 (New York City Press: New York), pp. 328–29

![Relief panel with scenes from the life of Christ (Massacre of the Innocents; Baptism of Christ; Marriage at Cana) by Unknown Byzantine artist [Rome or Milan]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0516_Unknown+Byzantine+artist_Relief+panel+with+scenes+from+the+life+of+Christ_ART557036_cropped.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Robin Jensen