Psalm 88

The Psalter’s Darkest Hour

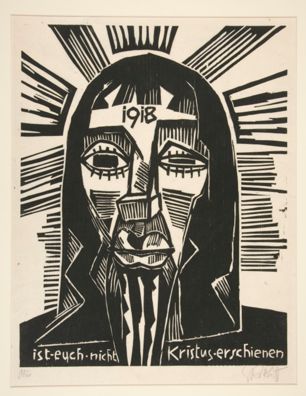

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

Kristus (Christ); Did not Christ Appear to You ('Ist euch Kristus nicht erschienen'), 1918, Woodcut, 320 x 742 mm, Yale University Art Gallery; 1941.675, Courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery

‘Did Not Christ Appear to You?’

Commentary by Jacob Phillips

The process of making a woodcut is violent. The work is formed by gouging wood with a chisel, like an axe in miniature.

When the German expressionist artist Karl Schmidt-Rottluff made this woodcut in 1918, an axe had been laid to Europe’s roots. It was a decimated forest.

Only ten years previously, a civilisation suddenly quickened by the promethean light of electricity seemed to be witnessing the breaking through of a new era. Schmidt-Rottluff was originally associated with this exploratory and playful milieu. But this same capacity for innovation then afforded new ways to inflict suffering.

His woodcuts may be seen as mirroring the indiscriminate brutality that ensued. But Schmidt-Rottluff used them to hack his way through to the beating heart of European art: its Christian iconography. (This print was part of a series of eight woodcuts on New Testament themes.) In a sense he was like the Psalmist of Psalm 88; outlining a harsh contradiction between promise and fulfilment. He recalled how once-civilized peoples had formerly seen themselves, while simultaneously lamenting how they had turned out.

Machine-gun fire leaves no room for shades of grey. Schmidt-Rottluff chose black-and-white.

Christ’s face itself seems to be wooden, as though itself a carved object. The square stub of the nose speaks of artifice; it exposes that which is humanly-formed as primitive and crude. His left eye is swollen and squinting like the black-eye of a bar-room brawler, and both eyes have roughly-cut black rectangles for their conflated irises and pupils, making it difficult to apportion any specific emotion to the face.

Something cryptic is indicated by the gouged-out date on the forehead. One might expect the letters INRI here, the quintessential scriptural locus of a contradiction between promise and fulfilment. Schmidt-Rottluff leaves a question to his contemporaries suspended in mid-air, ‘did not Christ appear to you?’. He reminds his viewers of the giddy heights of their original prospects as human creatures, while simultaneously plumbing the depths of their devastation. In this way, his work mirrors the refusal of the Psalmist to give way entirely to either hope or despair.

References

Elger, Dietmar. 2002. Expressionism: A Revolution in German Art (Köln: Taschen Verlag)

Roger Hiorns

Copper Sulphate Chartres & Copper Sulphate Notre-Dame, 1996, Card constructions with copper sulphate chemical growth, Perspex cover, 137 x 125 x 65 cm, Saatchi Gallery; © Roger Hiorns, courtesy of the artist and Corvi-Mora, London; Saatchi Gallery; Photo Courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery, London

Undoings

Commentary by Jacob Phillips

A great Gothic cathedral is not just a beautiful building, but a miniature cosmos replicating the worldview of medieval Christendom. It is as though the universe as described by Thomas Aquinas’s Summa or Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy had been realized in three-dimensions.

Modern science has now claimed the cosmos and repeatedly rewritten its narratives afresh, with little or no acknowledged help from sacred tradition. Human civilisation constructs ever taller buildings, many of them striking in their bold ingenuity, but lovers of Scripture can no longer impart a theocentric vision to the world they inhabit—or to its ongoing history—with the simplicity of that former age. Reading today’s world through the world of Scripture involves as much loss as it does gain, as much exile as homecoming.

Contemporary British artist Roger Hiorns evokes the frailty of this past by rendering two paradigmatic Gothic edifices, the Cathedrals of Chartres and Notre Dame, in thin, fragile cardboard. These great testaments to a past civilisation appear on close inspection to be delicate and transient. A sense of their inevitable disintegration seeps out in the copper sulphate growths that overpower their hosts and threaten to consume them. These crystalline ‘tumours’ speak of the blind and insurmountable force of nature in a scientific age. Yet the blue also seems luridly unnatural in this context, suggesting that modern humanity’s reverence for science can breed a jarring grandiloquence of its own—much more confounding than anything from the ‘primitive’ past.

Today’s lover of Scripture is caught between capitulating to the architectonic pressures bearing down on the text, or a retrograde denial of twenty-first century complexity. Speaking down the centuries, Psalm 88’s continued lamentations in the darkness seem to give voice to the interpenetration of loss and gain that emerges from living at the intersection of these worlds.

Psalm 88 is not easy reading. It has no comfortable resolution nor easily perceived sense of hope. The Psalm could even be read as a moment within Scripture that describes the text’s own undoing, and which thus offers a juncture peculiarly analogous with living by Scripture in the fact of our apparently inexorable, contemporary void.

Lucas Cranach the Younger [?]

Christ as the Man of Sorrows, c.1537, Oil on beech panel, 51.2 x 34.5 cm, Owned by Freie Hansestadt Bremen, Stadtgemeinde. On long-term loan to Kunstsammlungen Boettcherstraße, Bremen; DE_KBSB_B56, Photo: Courtesy of the Kunstsammlungen Boettcherstraße, Bremen

Opening the Darkness

Commentary by Jacob Phillips

Lucas Cranach the Younger’s Christ as the Man of Sorrows sits in a long tradition of devotional art focused on Christ’s afflicted body and concerned to awaken our pity. With its eerily sentient Jesus, shown in the dark interval between crucifixion and resurrection, the work fits a classically Christian interpretation of Psalm 88—arguably the Psalter’s ‘darkest hour’. It is the only psalm that does not sound a note of hope at its end.

Christ’s body is here shown as wounded and broken. Since its manufacture, this painting’s viewers have come before it to lament over some personal circumstance leaving them ‘like one forsaken among the dead’ (v.5). They might gaze into the eyes of Jesus, and feel the compassionate sorrow pouring forth from his face, assured that their entreaties will be heard: ‘incline thy ear to my cry!’ (v.2).

Yet, Christ is shown crucified, not risen. Maybe the lamentations brought before this image, like the Psalmist’s, remain unresolved. No illnesses healed. No bereavements undone. Entering into such an unassailable forsakenness is a treacherous byway of faith, but the Psalmist insists on articulating it, commenting on his own unanswered petitions: ‘Why dost thou hide thy face from me?’ (v.14).

As even this pleading is left echoing in the darkness, the Psalmist thinks the unthinkable: that there is some malevolence to God. ‘Thy dread assaults destroy me’ (v.16). But this God who seems to have approached his creature with only sorrow and pain is not rejected, and instead the lament continues. At this most frightful moment of belief, the one praying continues to decry the misfortune befalling him or her: ‘my companions are in darkness’ (v.18).

Thus, a yet more genuinely unthinkable reality emerges, of a God whose ways are the undoing of all human ways but whose face is human and whose name is love. Though this man of sorrows is crucified, he gazes intently, intimately at us. Opening the darkness of his wound to us, he seems silently to plead from within his grave.

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff :

Kristus (Christ); Did not Christ Appear to You ('Ist euch Kristus nicht erschienen'), 1918 , Woodcut

Roger Hiorns :

Copper Sulphate Chartres & Copper Sulphate Notre-Dame, 1996 , Card constructions with copper sulphate chemical growth, Perspex cover

Lucas Cranach the Younger [?] :

Christ as the Man of Sorrows, c.1537 , Oil on beech panel

Songs of Experienced Innocence

Comparative commentary by Jacob Phillips

The Book of Psalms has accompanied people's devotions for centuries, forming the basis of regular patterns of prayer and worship.

It has been argued that the full sweep of human experience in faith is somehow caught up in its 150 poetic songs (Brueggemann 2002: 8–10). The book as a whole can be approached as starting out with straightforward living in faith (Psalm 1), then entering into the experience of deep challenges to this faith, before finally (Psalm 150) ascending into a cacophony of praise (Brueggemann 2002: 12). These are not just songs of innocence and experience, but also songs of innocence regained, or better, songs of an experienced innocence.

Psalm 88 is the very nadir of this exitus and reditus; this departure and return. It does not in any way resolve its lament with promise or hope. It ends like an echoing question searching for an answer, which rebounds around the walls of a cavernous tomb. It is associated with the entombed Christ in the abyss between death and resurrection. In many Christian traditions, it is prayed at night prayer on Fridays, marking the darkness of nightfall after the crucifixion, before the dawn of the resurrection has begun to colour the horizon.

The human moments to which this Psalm speaks are of course moments of sorrow and loss. But by ending without comfort, its lament offers what might be termed a ‘finality of non-resolution’ (Janz 2004: 21–22), capturing the sheer incomprehensibility of some human sorrows. The Psalm thereby unearths something of human encounters with the God who is intrinsically beyond human understanding, the God who can act in a sovereign freedom which is not accountable to any creaturely demands for justification whatsoever.

In this exhibition, three intersecting moments of a peculiarly confounding sorrow are portrayed: individual/personal (Lucas Cranach the Younger), civilisational/historical (Karl Schmidt-Rottluff), and architectonic/cosmic (Roger Hiorns). Taking these images together, the manifold ways in which Scripture discloses itself as authoritative and meaningful in contexts vastly different from the world in which it was written can be glimpsed.

To read the Psalms, rather than pray them, may be like viewing Cranach the Younger’s painting as an art object, rather than devotionally engaging with it. Cranach sets up a divine-human encounter in the form of a very difficult dialogue (indeed, a ‘dialogue’ which has only one speaker whose petitions seem to go unanswered). The fact that the Psalmist continues to lament in the face of such desolation might be interpreted as a refusal to accept that there is not some other horizon out there somewhere, even if such a possibility is utterly impossible to envisage at that moment. There is no glimmer of resurrected glory, yet Cranach’s Christ is not only, or straightforwardly, dead.

Schmidt-Rottluff sets up a relationship between viewer and object which is very different, but communicates the same sense of confounding sorrow. Here, Christ resembles a wooden sculpture, quite literally, but his halo emits dramatic rays of light. The image contains both promise (allusions to traditional iconography) and that promise’s brutal contradiction. The date ‘1918’ speaks of the ‘finality’ of death, whose weight the Great War visited emphatically on the world’s consciousness, and yet frames it in the ‘non-resolutional’ context of a once-given promise that might yet still hold.

Hiorns’s sculpture shows how the world of art, like the world of Scripture, can provide meaning in contexts vastly different from their original ones. By its acknowledgement of how history dismantles the fixed edifices of earlier times, his work provokes reflection on the task of interpreting Scripture in a world from which Scripture is exiled. In Gothic cathedrals, images of salvation history were intricately wedded with a cosmic vision of geometric harmony. But the universe is far bigger, older, and more volatile than the Gothic architects could have imagined, and even once-mighty cathedrals might now seem dated and even insignificant attempts to harness the power of nature and to buttress human audacity, rather than offerings to the greater glory of God. Hiorns’s work suggests another grim finality—the decay of meaning as of materials. But even this finality remains unresolved as long as the horizon of the scriptural text can somehow brought to bear upon it—a task for which Psalm 88 seems uniquely equipped.

The strange tension of the Psalm may be perceived in all three of the artworks discussed here: the tension of trying to live in the midst of death, of being unable to forget promises even when they seem broken, and of homemaking in exile. In each artwork, songs of innocence can no longer be sung, but neither can they be extinguished completely by the deafening song of experience.

References

Brueggemann, Walter. 2002. The Spirituality of the Psalms (Minneapolis: Fortress Press)

Janz, Paul. 2004. God the Mind’s Desire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

![Christ as the Man of Sorrows by Lucas Cranach the Younger [?]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0229_CranachElder_Christ+as+the+Man+of+Sorrows_KB.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Jacob Phillips