1 Corinthians 13

Reflective Love

Unknown Roman artist

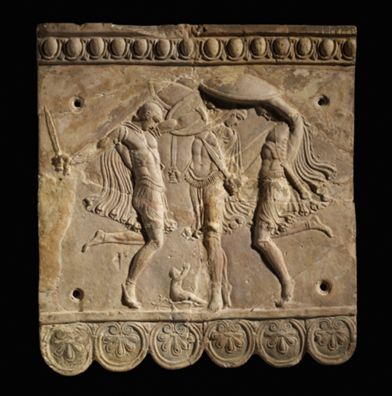

Terracotta Campana Relief of Three Curetes with Swords and Shields, Protecting the Infant Zeus, 50 BCE–100 CE, Terracotta, 51.4 x 46.35 cm, The British Museum, London; Purchased from Sir George Donaldson in 1891, 1891,0626.1, ©️ The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Cymbals and Self-enclosure

Commentary by Alison Milbank

This beautiful argument for the importance of active love as ‘a more excellent way’ (1 Corinthians 12:31) is part of an extended discussion about how Christians are to live in unity and use the charismatic gifts the Spirit has brought for the common good.

Paul, who has himself the gift of tongues (14:18), begins by comparing his ability for angelic speech to what might seem its opposite: a ‘noisy gong or a clanging cymbal’ (v.1). These instruments are far from the joyful cymbals of Jewish worship in the Psalms but shockingly evoke the cymbala of the ecstatic mystery cults of Cybele, all too familiar to Paul’s Corinthian audience. Rhea/Cybele’s guards originally clashed their brass weapons—and, taken literally, Paul’s words indicate ‘sounding brass’ (v.1, KJV)—to conceal the cries of the infant Zeus from being heard by his murderous father, Cronos, and the goddess’s initiates imitated this clamour in their rituals. References to ‘mysteries’ and moving mountains may refer to this story. This is sound intended to confuse and it embodies what Paul finds amiss about the charismatic gifts: they do not give themselves in the act of communication but rather enjoy their own self-expression.

A Roman terracotta relief illustrates the scene at Mount Ida with Rhea’s guards absorbed in their protective dance, their heads bowed, feet carefully aligned. Despite the sense of movement in the rippling cloaks against their muscular bodies, there is something hermetic and enclosed about their self-involvement, which is how Paul envisages his sounding brass, shorn of its relation to other instruments.

Nick Turpin

Through a Glass Darkly (On the Night Bus), 2014–17, Photograph; ©️ Nick Turpin

Love as a Mode of Knowledge

Commentary by Alison Milbank

The middle section of this chapter climaxes in a sense of fullness and inclusion, with the fourfold repetition of ‘all things’ matched by a fourth use of agapē in verse 8, where we learn that love never ends—literally, does not fall apart. This is contrasted to our own partial, transient human charismatic gifts and knowledge, which will not be needed in the eschatological future.

The practical centre of the chapter then modulates to the enigmatic and mysterious as it looks forward to a fuller understanding through love, which has an eternal value.

Nick Turpin’s photograph of a child looking through the blurred glass of the bus window embodies our present existential lack of knowledge. It is part of a sequence, ‘Through a glass darkly’, which plays on the pun possible in the King James translation of verse 12, between transparent windowpane and opaque-looking glass.

We glimpse the young girl through a medium of misted glass as if we were passengers on another passing vehicle, but intimately, catching her thinking. Holding a mobile telephone, she is distanced from us as she attends to another person and situation. Her gaze, however, is unfocused, as if she looked inward to regard a mirror of reflection.

The Greek for ‘in a mirror dimly’ is ‘in a riddle’ (ainigma). Like that mysterious child on the bus, we are all enigmas to ourselves and other people. Paradoxically it is the eyes of love which acknowledge the mysterious depths in the other; to realise that we are all children in our limited understanding of the world is the beginning of wisdom. To be aware of partial vision is to open that long vista of meaning that makes a clear halo round the girl’s head, as though gesturing to that loving circling of the divine persons, in which she, like us, is fully known.

Pieter Bruegel I

One of the Seven Virtues: Caritas (Charity), 1559, Pen and brown ink, indented, framing lines with the pen in brown ink on paper, 224 x 293 mm, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam; formerly Franz Koenigs collection, N 18 (PK), HIP / Art Resource, NY

Enacting Love

Commentary by Alison Milbank

In 1 Corinthians 13:4–8, Paul lays out what love should be, which is embodied vividly in a drawing by Pieter Bruegel the Elder for a series of engravings on the virtues. It is composed of scenes depicting the seven acts of mercy originating in the parable of the sheep and the goats from Matthew 25; here they are all directed by the central figure of Love or Charity/Caritas.

The child who conventionally clings to personified Charity at the centre of the composition, here pulls at her skirts to urge her to action. This parallels the structure of the Greek, for where RSV/NRSV uses a noun and adjective for clauses such as ‘love is patient’, they should more properly be rendered by active verbs and adverbs, so that ‘love waits patiently’.

As is typical of Bruegel’s busy scenes of peasant life, all is a whirl of activity, and each person engaged in charitable activity is eager to give—this is no patronising act of distant benevolence but ordinary people helping each other. Shirts are pulled over the heads and shoulders of the naked; loaves are proffered urgently in both hands by those feeding the hungry, their eyes directed at the needy. Two respectable citizens shake hands with the shamed criminals in the stocks. This is a hopeful scene of people communicating a sense of loving kindness.

Charity has a pelican on her head, an image of Christ’s self-giving as the pelican was popularly believed to feed her young from her own breast. It reminds us that verses 4–7 in which love ‘bears all things … endures all things’ refers above all to Christ. The Greek word for ‘love’ or ‘charity’ is agapē, used throughout the New Testament for God’s gratuitous outflowing of love, which Paul here offers as a way for humans to follow by participation.

Unknown Roman artist :

Terracotta Campana Relief of Three Curetes with Swords and Shields, Protecting the Infant Zeus, 50 BCE–100 CE , Terracotta

Nick Turpin :

Through a Glass Darkly (On the Night Bus), 2014–17 , Photograph

Pieter Bruegel I :

One of the Seven Virtues: Caritas (Charity), 1559 , Pen and brown ink, indented, framing lines with the pen in brown ink on paper

Ascending and Descending Love

Comparative commentary by Alison Milbank

Bronze objects begin and end this chapter, appropriately since Corinthian smiths were known for their manufacture of shields and cymbals as well as bronze mirrors, which imitated their concave shape.

Without the interpretive key of love, however, their duality remains locked in, unable to communicate. Even Christian prophetic powers and faith to remove mountains are of no avail without the third term, love, which orients them beyond the self and its capacities.

The play of duality and the triad is woven into the intricate movement of this chapter from beginning to end, with opposites like transience and stability, and the duality of self and other that opens the dyad to triadic divine fullness: to faith, hope, and love. The dancing guards in the Roman relief form a selfless triad and the toe of the central dancer reaches out beyond the frame. Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s figures are similarly learning to live beyond the self through love and they do this by imitating Christ, represented in the drawing by Charity. Next to her is another woman with a child urging her to action, veiled and old, in comparison to Charity’s youth and unveiled, flowing locks. As a pair they illustrate tellingly Paul’s point about the difference that Charity makes to our actions. It is not so much that the veiled woman is judged but that she is called to be transformed. Charity offers the key to effective action in the heart she offers, showing that we are invited to participate in the loving action of God.

Paul writes in 2 Corinthians 3:18: ‘all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another’ (NRSV). We are called to unveil and be directly involved like Charity, even though we as yet see God’s glory only reflected. That reflection, however, here is conveyed by the perfect mirror, Christ himself. Imitation calls us to be loving as Christ is, and to ourselves become reflections of the divine love. At the front of the Bruegel drawing is a pile of clothing ready to be put on because Christians are to dress themselves in Christ, as Paul writes in Galatians 3:27. For we are the recipients of charity as well as those who dispense it.

Thomas Aquinas, in response to this chapter of 1 Corinthians, made love the form or shaping purpose of the other virtues. Like faith and hope it is a gift infused into the soul by the Holy Spirit, directing our actions and our loves to their true goal in God, if we will accept the gift. To be human is to be like the young girl in Nick Turpin’s photograph, with a gaze beyond the confines of the self and the mirror of this world. This chapter juxtaposes the serene stability of God’s overflowing agapē with human desire to connect with it, which being in time and imperfect, is erotic: needy and striving. Benedict XVI described these two modes as ‘ascending and descending’ love.

In the Bruegel drawing the contrast is conveyed by the loving attention and downward gaze of Charity and the upward neediness of the child pulling at her skirts as well as the desperate gestures of the hungry. Yet, the man to Charity’s right offering bread shares her agapeic regard in a broad smile of welcome. He is stable within the press of people, showing that humanity can share in God’s descending love and communicate it in action.

The dance of Zeus/Jupiter’s guardians might seem worlds away from this Pauline theology. It too, however, is an act of communication, of protection and love. The divine child reaches out his arms with the utter neediness of the infant, sheltered by the carapace of the agapeic self-giving of his protectors: eros and agape, ascending desiring and descending selfless love, so that they too convey something of a love that never ends.

Commentaries by Alison Milbank