Leviticus 15–18

Scaping Sin

Tracey Emin

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (The Tent), 1995; destroyed 2004, Appliqued tent, mattress, and light, Formerly owned by Charles Saatchi; destroyed in Momart warehouse fire, 2004; All rights reserved DACS / Artimage, London and ARS, NY 2018. Image courtesy White Cube

A Tent of Meetings

Commentary by Sheona Beaumont

Tracey Emin’s tent rose to public prominence at the height of the Young British Artists movement in the mid-1990s, being included in the Royal Academy’s 1997 Sensation exhibition. Featuring the names of family members, lovers, and friends (and two numbers to represent two foetuses) sewn in patchwork in the lining of the tent, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With was received with a mixture of ridicule and disgust.

Leviticus 15’s stipulations for bodily cleanness concern situations of intimacy between men and women. Emin’s tent examines the realness and messiness of close living. Both the biblical text and the artwork have generated polarized responses centred wholly on sex. Yet in fact both are also concerned with bodily functions and relationships that are non-sexual. Emin explores companionship with another when pregnant or simply asleep; the text attends to genital discharge in general, not just in sex, making the quest for a pure relationship before God its key concern (and opposing the cult of fertility prevalent in Israel’s neighbouring cultures).

In both text and artwork, the value of intimacy is preserved, together with its detail. Leviticus 15’s washing of body, clothes, and furniture after contamination, the point-by-point counting of days and hours, and the sacrificial presentation at ‘the door to the tent of meeting’ (vv.14, 29) hold a fabric of reconciliation in view—among people and between people and God. In much the same way, Emin’s material lettering, stitching, and the tent-form itself, convey a circumscribed wholeness, and suggest an attempt at reconciliation with her past, in a space with resonances of sanctity.

Our initial moral instincts might want to contrast biblical proscription (Bird 2015: 151) with artistic exhibitionism. Divine commands seem like arbitrary and inhuman impositions; Emin’s feminism nothing but their defiant ‘correction’. And of course, the Mosaic Law’s radical new standard of relationship—holiness—between the Israelites and their God contrasts with Emin’s human reach for a human bridge across gender, age, and non-sexual/sexual categories. But this would miss the remarkable intimation of the divine that is discernible in both. Together, they might lead us to renewed consideration of the theological horizon of human living itself.

References

Bird, Phyllis A. 2015. ‘The Bible in Christian Ethical Deliberation Concerning Homosexuality: Old Testament Contributions’, in Faith, Feminism, and the Forum of Scripture: Essays on Biblical Theology and Hermeneutics (Eugene: Cascade Books), pp. 127–62

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin

Leviticus, part of Divine Violence, 2013, King James Bible, Hahnemühle print, brass pins, 101 x 112 x 5 cm, Collection of the artist; Edition of 3, © Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin; Courtesy of the artists and Goodman Gallery

An Unclean Concentrate

Commentary by Sheona Beaumont

The voice of God dominates Leviticus. It is a voice of great clarity but one which can seem concerned largely with negation. Its preoccupations with the ‘unclean’ (Hebrew: tame) are found in their most concentrated form in chapters 15–18.

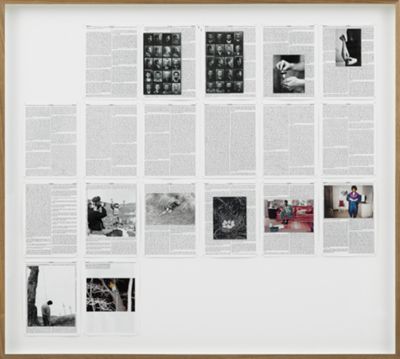

Adam Broomberg’s and Oliver Chanarin’s work Holy Bible (2013) incorporates over 500 photographs selected from the Archive of Modern Conflict across a complete Bible, superimposing the images on every double-page spread—except the pages on which Leviticus 15–18 appears. At this point in the text visual images disappear dramatically and, instead, the word ‘unclean’ is underlined in red whenever it occurs.

The striking effect can be seen in this photograph, in which a framed display of the artists’ Leviticus pages becomes suddenly denuded of images in the second row.

The artists have said that they approached the Archive in the spirit of a word–image collaboration, inspired by Bertolt Brecht’s own photograph-plastered Bible. For Broomberg and Chanarin, the expansive reach and witness of photographs of life in its extremes, particularly in suffering and war, was a suitable fit for the Bible’s mode of telling us everything, particularly in Old Testament accounts of conflict and violence. Yet in this section of Leviticus, the almost myopic intensity of focus on individual human uncleanness (as opposed to larger issues like genocide) seems to act as a kind of perceptual cul-de-sac for the artists. They can’t find photographs for it; it seems unvisualizable for them.

If these chapters give an in/out impression of divine judgement evoking a visceral and personal rejection by God (the defiled are ‘cut off’ in Leviticus 17:4, 9 or ‘vomited out’ in Leviticus 18:25) then this may cause us to miss a paradox. For the text also signals God’s desire to draw near to humanity, by making humanity fit for divine contact. God’s words of judgement harbour the possibility of their own inversion. Broomberg’s and Chanarin’s work may do something comparable. When the photographs return with Leviticus 19, it is verse 2’s ‘I am holy’ which is underlined, opposite a photograph of a combat-dressed child, arms raised in a position of surrender.

Humanity’s uncleanness and defiance may find itself both judged and summoned by a holiness that seeks the world’s return in innocence: the child under the battle-dress.

James Tissot

Agnus-Dei: The Scapegoat (Agnus-Dei. Le bouc émissaire), 1886–94, Opaque watercolour over graphite on grey wove paper, 256 x 171 mm, Brooklyn Museum; Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.265, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA / Bridgeman Images

A Painful Transference

Commentary by Sheona Beaumont

Unlike William Holman Hunt’s more famous painting of the forlorn scapegoat, his contemporary, James Tissot, painted Agnus-Dei: The Scapegoat (1886–94) as a scene of high drama. Starting with Leviticus 16’s description of the scapegoat upon whose head the sins of the community are transferred, Tissot focusses on the dynamism of this living sacrifice. We see a populated, animated landscape showing the moment when the scapegoat is driven into the wilderness (Leviticus 16:21–22), enhancing the scene with a descriptive realism that is not there in the text.

Tissot was a French impressionist painter whose turn to realism was accompanied by a turn to biblical subjects. Visiting the Holy Land in 1886–87 and 1889, he made careful studies which contributed to a series of 365 watercolours illustrating the life of Christ, now in the Brooklyn Museum.

Undoubtedly, we are meant to feel the physicality of place in this scene: the aridity of the land and the hurtling rocks plunging vertically downward honour the Levitical law’s first context. But we also seem encouraged by the work to feel an intertextual resonance with the New Testament, and John 1:29’s ‘Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world’. Indeed, Tissot’s figure and his pinched face is the Jesus of his earlier paintings, not only carrying a lamb, but also propelled forward in front of the scarlet-threaded head of the fleeing goat.

Neither the reconciling blood of the animals sacrificed back in the camp’s sanctuary, nor the priestly communion in the Most Holy Place of that same sanctuary, are present in the composition. In this Christian typological transformation of the ritual, Tissot is making sure we see the singularity of Jesus’s atoning figure alone.

The ‘Lamb of God’ here is rendered without ambiguity. There is instead an uncomplicated affirmation of the sacrificial efficacy of God’s actions in Jesus. The Hebrew text, by contrast, pointedly includes Aaron (Leviticus 16:1, after the death of his two sons in 10:1–2). Might this suggest a more painful transference—less a moment in which past sin is neatly jettisoned than a ritual before God in which humanity faces and wrestles with itself?

Tracey Emin :

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (The Tent), 1995; destroyed 2004 , Appliqued tent, mattress, and light

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin :

Leviticus, part of Divine Violence, 2013 , King James Bible, Hahnemühle print, brass pins

James Tissot :

Agnus-Dei: The Scapegoat (Agnus-Dei. Le bouc émissaire), 1886–94 , Opaque watercolour over graphite on grey wove paper

Hingeing on Holiness

Comparative commentary by Sheona Beaumont

In some respects, Leviticus seems to stand apart from other parts of the biblical text: a long list of laws and prohibitions, ‘an unappetising vein of gristle in the midst of the Pentateuch’ (Damrosch 1989: 68). A legacy of centuries of often baffled interpretation has legitimized the labelling of ‘uncleanness’ laws in particular as primitive and irrational, explicable in terms of a socio-disciplinary ethic, perhaps even a pseudo-medical one.

Here, the artworks under consideration help us to reframe our modern reactions to the style and substance of Leviticus 15–18 by attending to aspects of the laws’ theological significance: their sophisticated conceptualisation of uncleanness and the stitching of humanity’s sacred corporeality to God.

In Leviticus 15, we come to the end of a section of purity laws (chapters 11–15) pertaining to animals, skin diseases, and latterly, genital discharges (male and female). Chapter 16 follows with the priestly instructions for the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur, later described in Leviticus 23) and the treatment of the scapegoat (Azazel). Chapters 17 and 18 begin what is Leviticus’s second half, the Holiness Code, a body of ordinances that seems likely to have been separately inserted. It is loosely directed to the people as a whole, and is more disparate in style than the first part of the book (widely identified as the ‘priestly’ or ‘P’ source). In this case, the subjects pertain to the sanctity of an animal’s blood (Leviticus 17) and of family relations (Leviticus 18).

Something of a hinge in the book, Leviticus 15–18 forms a section which constitutes, in Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s Holy Bible (2013), a visual lacuna in a Bible otherwise covered in photographs. In their work, the word ‘unclean’ receives the prominence it has in these chapters: a concentrated 98% of the total number of occurrences of the term in Leviticus as a whole.

A hinge, a lacuna, and a concentrate: Leviticus 15–18 has these qualities. In what has something of a resonance with the opening chapters of Genesis, the post-Edenic relationship with God is being defined not through narrative but through an account of God’s ordinance whose highest concern is union and atonement. The marking of two goats in Leviticus 16 clearly differentiates between either a centred or a decentred life, either a state of being with YHWH at the centre of the Israelite camp or removed from YHWH in the chaotic wilderness. Indeed, while God speaks to Moses from the tent of meeting (Leviticus 1:1), the people do not move from the base of Sinai, and the priests confirm the concepts of purity and holiness (vertical relation to God) over and above the strata of ritual custom (horizontal relation to the world).

When the horizontal comes into play, this vertiginous state of vertical relation to God becomes also precipitous: a tension that is dynamically captured in James Tissot’s painting Agnus-Dei: The Scapegoat (1886–94) where we are in danger of flying rocks. We see a hinge, both in the above/below peopling of the landscape, and in the directionality of the main figure of Jesus who serves to introduce an Old Testament/New Testament typology into Tissot’s view. In its vertical axis, the painting is like Leviticus 16’s conceptual and ideal centre at the heart of the Israelites’ focus on God. In its horizontal movement, it hurtles towards potential death.

A closer inspection of that to which chapter 16 is hinged reveals one of the most misunderstood aspects of Israelite moral standards. Even though so much is about purification and defilement laws between God’s people, ‘there is absolutely no sign of social demarcation maintained by pollution rules’, and this is strikingly different from other Near-Eastern cultures (Douglas 1995: 240). The kind of interpretative eclipse here, whereby the ancient text is not read with proper attention to its concern with cultic purity, is mirrored in the way that Tracey Emin’s Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (1995) is also interpreted. A sensationalist rhetoric commonly denies her careful and inclusive accounting of human reciprocity. Hers is as principled a declaration of non-hierarchical personhood as that which rings out from Leviticus 19:18’s ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself’, yet it also unavoidably relates to the physical register of sex and bodily function in chapter 15.

In chapter 18’s even more stringent terms, the proscriptions surrounding bestial and homosexual behaviour warrant an even more sensitive contextualisation of what was a differentiation from other cultures’ ritual practices. Here, it is Broomberg and Chanarin’s image of a child ‘giving up’ on the path of violence that dissolves the intensity of the ‘unclean concentrate’. It evokes purity of worship, and radical newness of relationship—just those things that so underpin the laws of Leviticus 15–18.

References

Damrosch, David. 1989. ‘Leviticus’, in The Literary Guide to the Bible, ed. by Robert Alter and Frank Kermode (London: Fontana Press), pp. 66–77

Douglas, Mary. 1995. ‘Poetic Structure in Leviticus’, in Pomegranates and Golden Bells: Studies in Biblical, Jewish, and Near Eastern Ritual, Law, and Literature in Honor of Jacob Milgrom, ed. by David P. Wright, David Noel Freedman, and Avi Hurvitz (Pennsylvania: Eisenbrauns), pp. 239–56

Watts, James W. 2007. Ritual and Rhetoric in Leviticus: From Sacrifice to Scripture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Whitekettle, Richard. 1996. ‘Levitical Thought and the Female Reproductive Cycle: Wombs, Wellsprings, and the Primeval World’, Vetus Testamentum, 46.3: 376–91

![Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 [The Tent] by Tracey Emin](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0216_TraceyEmin_EveryoneIHaveEverSlept+With_AI.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Sheona Beaumont