Hosea 4

Time for a Change

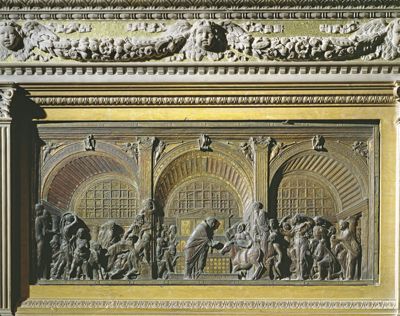

Donatello

The Ass of Rimini Kneeling before the Host, Main altar, 1447–50, Bronze, 57 x 123 cm, Basilica of Saint Anthony, Padua; Bridgeman Images

A Stubborn Heifer

Commentary by Joost Joustra

Like a stubborn heifer, Israel is stubborn; can the Lord now feed them, like a lamb in a broad pasture? (Hosea 4:16)

Modelled in bronze relief by Donatello, St Anthony of Padua’s miracle could be read as a response to the prophetic question posed in Hosea 4. The townspeople of Rimini here stand in for the Israelites, and a mule performs the part of the heifer.

Anthony presented the beast of burden with the Blessed Sacrament, after the animal’s heretical Cathar owner had denounced Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. The mule, having been starved for three days straight, was presented with a choice between his meal and the Host. In front of what seems to be an altar, the result of Anthony’s experiment takes centre stage, highlighted by Donatello’s tripartite classicizing architecture. The animal not only prefers the Host’s spiritual sustenance to his feed; it even kneels in reverence. Ultimately, its owner would follow suit and become one of Anthony’s most pious followers.

The bronze relief was probably positioned on the back of the High Altar in Padua’s most important church: the Basilica dedicated to St Anthony. It was placed next to a locked tabernacle that would have contained the actual Host, the tabernacle in turn flanked on the other side by a relief of St Anthony’s Miracle of the New-Born Babe. By their placement, the two scenes had their meaning amplified through eucharistic connotations (Johnson 1999: 653–54).

‘Can the Lord now feed them?’. The answer to Hosea’s rhetorical (?) question is a ‘yes’ in Donatello’s relief. We see the mule, so reputedly stubborn—as, by extension, is his owner—turning from a heifer into a ‘lamb in a broad pasture’ (v.16).

References:

Johnson, Geraldine A. 1999. ‘Approaching the Altar: Donatello’s Sculpture in the Santo’, Renaissance Quarterly, 52.3: 653–54

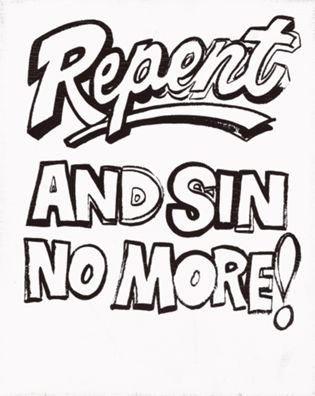

Andy Warhol

Repent and Sin No More! (Positive), 1985–86, Synthetic polymer and silkscreen ink on canvas, Private Collection; © 2011 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo © Christie's Images / Bridgeman Images

The More They Increased

Commentary by Joost Joustra

Besides celebrating Andy Warhol as the quintessential artist of his time and place—the artist who held the most revealing mirror up to his generation—I’d like to recall a side of his character that he hid from all but his closest friends: his spiritual side. (Richardson 1992: 140)

With these words, the art historian John Richardson revealed Warhol’s hitherto ‘hidden’ Catholicism, in his eulogy addressed to the crowds that had gathered for the artist’s memorial service at St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York in 1987. He made this perhaps surprising remark not long after Warhol had made Repent and Sin No More!.

Warhol’s inherently verbal work reads as a warning, as does Hosea 4’s address to the Israelites: the classic prophetic call ‘Hear the word of the Lord, O people of Israel’ (v.1) is followed some sentences later by ‘the more they increased, the more they sinned against me’ (v.7). The people of Israel heard, but did not listen.

Notions of re-use and increase are fundamental to Warhol’s oeuvre. Reproduction and repetition are the artist’s trademark. For Repent and Sin No More!, the appropriated image took shape in two versions, a ‘positive’ and a ‘negative’, inverting the sober black-and-white of lettering and background. Their monochromatic make-up puts these works in a longstanding Christian tradition. In medieval and early-modern Europe for instance, black, white, and greys were used in the visual culture of Lent as a means for marking this period of penitence (Sliwka 2017: 27).

Repent and Sin No More! may in this sense pick up on the penitential associations of monochromatic art, in a reproducible medium and with the formal qualities that Warhol employed ever since he designed advertisements early in his career. Like Hosea’s Israelites, of whom he complains that the more they increased the less they listened, Warhol’s work in essence explores the same concept by using a mass reproduced text/image aimed at a rapidly increasing American population, an audience that was possibly equally inattentive.

The positive and negative versions of Warhol’s work furthermore emphasize that his audience has a choice, one leading towards light, the other to darkness. Perhaps the ‘mirror’ held up to his generation, to which Richardson’s eulogy referred, was most confrontational in Warhol’s last works, especially Repent and Sin No More!.

References:

Richardson, John. 1992. ‘Eulogy for Andy Warhol’, in Andy Warhol: Heaven and Hell Are Just One Breath Away! Late Paintings and Related Works, 1984–1986 (New York: Rizzoli), p. 140

Sliwka, Jennifer. 2017. ‘Painting the Sacred’, in Monochrome: Painting in Black a White by Lelia Packer and Jennifer Sliwka (London: National Gallery), p. 27

Pieter Aertsen

A Meat Stall with the Holy Family Giving Alms (The Butcher's Shop), 1551, Oil on panel, 115.6 x 168.9 cm, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Purchased with funds from Wendell and Linda Murphy and various donors, by exchange, 93.2, Bridgeman Images

They Shall Eat, But Not Be Satisfied

Commentary by Joost Joustra

If this indeed is A Butcher’s Shop or a Meat Stall, one wonders why two fishes (herring?) are displayed on a pewter dish among this cornucopia of meat. However, looking closely, a great variety of different foodstuffs appears. Among the beef, pork, and poultry, there are kippers too, and pretzels, pies, and dairy products, bathing in painterly light. Hosea’s ‘beasts of the field’, ‘birds of the air’, and ‘even the fish’, are here shown as having been ‘taken away’ by man (Hosea 4:3).

Then, the viewer is drawn to what could be called a background, but one that counterintuitively contains human action. On the right, a man is filling an earthenware jug with water from a well, surrounded by scattered oyster shells. Beyond, a second hung carcass acts as a curtain to an interior scene, with men and women around a table in front of a fireplace, appearing to have a sinfully good time. In the left background, a scene that is familiar: an older man guiding a woman on a donkey carrying a small child. This must be the ‘flight into Egypt’ of Joseph, Mary, and the infant Jesus.

Only then does one realize that the Holy Family is painted right above the fishes. The fishes, in fact, are crossed, and look like a crucifix. They are a clue to the fact that—beyond the narrative in the left background—Pieter Aertsen’s horror vacui ‘still life’ contains many explicit and implicit Christian references.

It balances virtue and vice. In the flight into Egypt scene Mary is handing out alms—or one could call it ‘spiritual food’ (Craig 1982: 6). Meanwhile, its counterpoint on the right appears in fact to be a brothel scene, invoking temptations of the flesh; flesh that is quite literally offered to the Butcher Shop’s ‘visitor’. The passage from Hosea seems to sum up this part of the composition well: ‘They shall eat, but not be satisfied; they shall play the harlot, but not multiply’ (4:10).

Aertsen’s plentiful painting seems to ask for introspection. Maybe, as well as temptation, there is redemption in the flesh as well—the very flesh that is fleeing to Egypt in the painting’s background?

References

Craig, Kenneth M. 1982. ‘Pieter Aertsen and the “Meat Stall”’, Oud Holland, 96.1: 6

Donatello :

The Ass of Rimini Kneeling before the Host, Main altar, 1447–50 , Bronze

Andy Warhol :

Repent and Sin No More! (Positive), 1985–86 , Synthetic polymer and silkscreen ink on canvas

Pieter Aertsen :

A Meat Stall with the Holy Family Giving Alms (The Butcher's Shop), 1551 , Oil on panel

Can the LORD Now Feed Them?

Comparative commentary by Joost Joustra

God’s accusation against the people of Israel in Hosea 4 reads as somewhat disjointed and repetitive at times, but the prophetic message is clear. In a series of oracles, YHWH denounces the Israelites’ worship of false gods, comparing their actions to adultery. Their behaviour is sinful, ‘swearing, lying, killing, stealing, and committing adultery’ (v.2), and God threatens them with punishment.

Yet, there is a glimmer of hope in this text: ‘Like a stubborn heifer, Israel is stubborn; can the Lord now feed them, like a lamb in a broad pasture?’ (v.16). These phrases seem crucial among the accusatory words that dominate Hosea 4, and point ahead to the pronounced possibility of repentance in Hosea 14: ‘Say to him: “Forgive all our sins and receive us graciously…”’ (v.14).

This glimmer of hope can also be found in the three works by Pieter Aertsen, Donatello, and Andy Warhol. Not immediately noticeable to the viewer, the ‘flight into Egypt’ painted in muted tones in the far background of Aertsen’s Butcher Shop—a desperate moment in the Holy Family’s life fleeing from Herod’s terror—also offers hope: ‘And so was fulfilled what the Lord had said through the prophet: “Out of Egypt I called my son”’ (Matthew 2:15). In fact, Matthew was echoing God’s Word from Hosea 11:1, ‘When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son’. In the midst of anguish, and in the background of a feast of flesh, Aertsen paints the fleeing Mary handing out food to a barefoot beggar. This tiny but meaningful detail is likely to be a eucharistic reference. As in Hosea, such details remind Aertsen's viewers that they ultimately have to look past earthly, fleshly temptations, to what is harder to see.

Andy Warhol’s appropriated message from an advert, on the other hand, appears entirely unambiguous at first glance. Repent and Sin No More!, together with the related Heaven and Hell are Just One Breath Away! from the same series, are late works made up of words instead of images. Their clarity is increased by the black-and-white contrast and their immediacy by their placard-like appearance. God’s words in Hosea’s prophecy address the people of Israel similarly: ‘The more they increased, the more they sinned against me; I will change their glory into shame’ (v.7). Just as Heaven and Hell are Just One Breath Away! gives the people a choice, so does Repent and Sin No More!. Human agency can lead to repentance, as the episode from St Anthony’s life depicted by Donatello in Padua also shows. Hosea’s faithless audience is condensed into a single heretic in medieval Rimini, the mule’s Cathar owner ultimately convinced by orthodox Christianity. The Miracle of the Mule leads to a dramatic moment of conversion for the Cathar—‘they shall be ashamed because of their altars’ (v.19)—while in Donatello’s narrative the Christian altar of the consecrated Host takes centre stage behind St Anthony.

Sinners are Hosea’s protagonists and addressees, just as they are to different extents in the works by Donatello, Aertsen, and Warhol. And ultimately, as becomes clear through the prophetic arc across Hosea’s fourteen chapters, these sinners can be saved.

Hosea’s ‘They shall eat, but not be satisfied’ (v.10) finds a counterpoint in Aertsen’s painting and Donatello’s relief sculpture, where the connotations of sustenance of the body by eating, and sustenance of the spirit through the Eucharist, are played out beautifully.

Warhol’s work is altogether more direct, but it too has affinities with Hosea. Both seek to amplify their cries. Warhol cleverly uses reproduction, repetition, and black and white, to give impact to his slogan. God in Hosea 4 reinforces his announcement to the Israelites through repeating what is essential: sinners will come to ruin. Warhol’s work echoes Hosea’s warning, continuing a prophetic tradition at an unexpected time and place. As John Richardson concluded in his eulogy for Warhol: ‘Andy’s use of a Pop concept to energize sacred subjects constitutes a major breakthrough in religious art’ (Richardson 1992: 141). Richardson was right for Warhol but could have equally been talking about Pieter Aertsen and Donatello, who (without Pop) ‘energized’ their sacred subjects through their artistic inventions.

References

Richardson, John. 1992. ‘Eulogy for Andy Warhol’, in Andy Warhol: Heaven and Hell Are Just One Breath Away! Late Paintings and Related Works, 1984–1986 (New York: Rizzoli), p. 140

Commentaries by Joost Joustra