Matthew 17:24–27

The Tribute Money

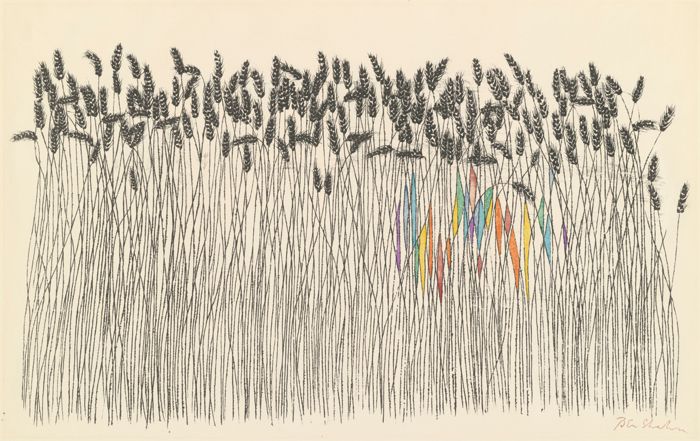

George Hayter

Saint Peter Paying the Tribute with a Piece of Silver Found in a Fish, 1817, Oil on canvas, 117 x 170 cm, Private Collection ?; © Sotheby’s, London

Hijacking Scripture

Commentary by Geoffrey Nuttall

George Hayter’s retelling of the episode of the Tribute Money relies less on the reading of Scripture as on the circumstances of its own commission.

The English artist was in Rome when he painted this work, in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, and in the entourage of his patron, John Russell, the sixth Duke of Bedford. Hayter adopts the style and palette of Roman seventeenth-century painting, and in the golden cloaked apostle pointing at the fish he cleverly references Christ’s gesture in Caravaggio’s famous painting of the Calling of Matthew, in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi. The figure might indeed be Matthew, once a tax collector at Capernaum, his cloak the colour of money, and his interest in the transaction stirring memories of his past.

The fresh-faced youth about to collect the tribute money is a disguised portrait of the 25-year-old artist. He is smartly kitted out as a Roman legionary, though the Byronic quiff protruding from under his helmet in a most unsoldierly fashion betrays his real identity.

The dramatic focus of the painting, despite its title, lies not with Peter and the tax collector, but with the brown-bearded disciple with receding hair. His forehead pushes against, as his gaze cuts across, the ridged vertical of the tax collector’s spear, his attention riveted on the bright silver shekel Peter tilts towards him like a tiny mirror. Christ meanwhile plays no part in the narrative, but looks away, abstracted in contemplation of the apostle whose finger presses into the gills of the dead fish.

The painting was commissioned as a gift for the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, president of the Roman artists’ guild, the Accademia di San Luca, as a tribute for Hayter’s admission to this revered institution. At the same time, the Duke of Bedford was in the process of acquiring Canova’s Three Graces, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The painting might, therefore, be seen as the painterly 'shekel' Hayter and the duke paid as their due to one of the early nineteenth century’s artistic ‘kings of the earth’: Canova. But might Christ’s detachment also be read as censure, of the worldly artist and his wealthy patron trying to buy their way in heaven with a painted coin?

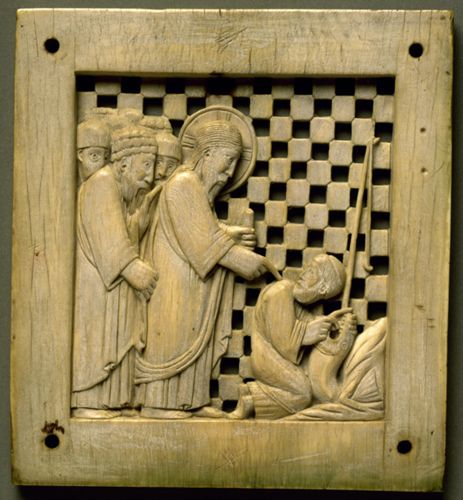

Unknown German or North Italian Artist

The Tribute Money, c.962–68, Ivory, 29 x 118 x 8 mm, National Museums Liverpool; M8062, © National Museums Liverpool / Bridgeman Images

Kings of the Earth

Commentary by Geoffrey Nuttall

Against a ‘checkerboard’ background, the figure of Christ dominates this small yet monumental ivory tablet, his disciples huddled behind him, mesmerized by the miracle unfolding before them. One clutches at Christ’s cloak, his other hand on the Saviour’s back, accentuating the heavy diagonal running down through Christ’s arm to the finger that presses firmly on Peter’s shoulder.

Christ, in imperious profile, looks down at the kneeling Peter, who responds to his touch of cold command by turning his head through an anatomically impossible 180 degrees. This inspired device within a compressed visual field enriches the tablet’s narrative power, portraying Peter simultaneously in the act of receiving Christ’s instruction, ‘go to the sea and cast a hook and take the first fish that comes up’ (Matthew 17:27), and its fulfilment, the finding of the shekel in the fish’s mouth.

The sinuous upward thrust of the fish, continued through the rod that caught it, creates a sharp vertical along the right hand edge of the tablet that brings the viewer’s attention back to the face of Christ, in a movement that perpetually reasserts his authority over the crouching Peter.

Commissioned as a gift from Otto I to his own ‘Temple’, the cathedral at Magdeburg, the tablet was probably part of an altar frontal made up of scenes from the Life and Miracles of Christ, a number of which have survived. The inclusion of the Tribute Money alongside more familiar miracles suggests that it had special meaning for its patron, the Holy Roman Emperor, perhaps as an assertion of his right as one of the ‘kings of the earth’ (v.25) anointed by God, to take tribute from his subjects, a right sanctioned by Christ in the shekel he commanded Peter to pay.

References

Lasko, Peter. 1979. Ars Sacra: 800–1200 (New Haven: Yale University Press), pp. 88–90

Little, Charles T. 1986. ‘From Milan to Magdeburg: The Place of the Magdeburg Ivories in Ottonian Art’, in Atti del 10 congresso internazionale di studi sull'alto medioevo, Milano 26–30 settembre 1983 (Spoleto: Centro Italiano di Studi sull'Alto Medioevo), pp. 441–51

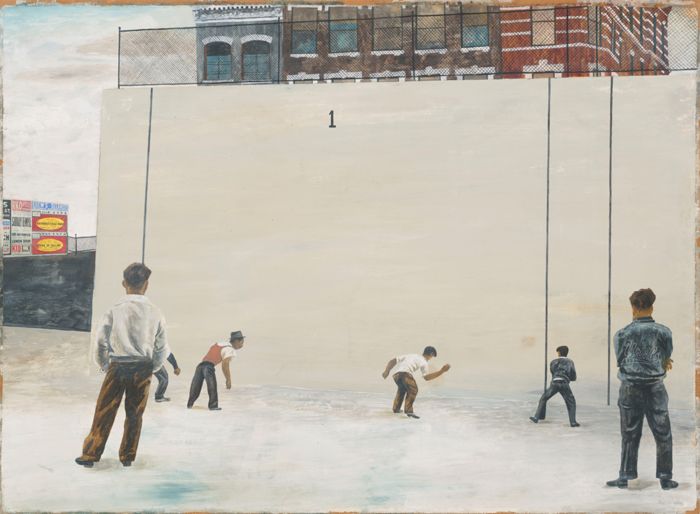

Masaccio

The Tribute Money, 1426–27, Fresco, The Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence; Scala / Art Resource, NY

Space and Time

Commentary by Geoffrey Nuttall

In this brilliant example of single point perspective, Masaccio uses the buildings of Capernaum to create orthogonals, the invisible lines that lead the eye to the vanishing point of the composition. They converge on the face of Christ, the figure dressed in blue and pink, who thus becomes the visual fulcrum of the painting.

Seen from behind, in dialogue with Peter, the tax collector stands before Christ at the extreme front edge of the picture space, his short tunic and naked legs indicating his low social status, in stark contrast to Christ and Peter’s patrician-like robes.

The strong directional light falling from right to left illuminates Christ’s face, casts shadows that lend sculptural form to the disciples ranged around him, and gives a sense of atmospheric recession to the landscape behind. Across the central axis of the fresco, Christ points magisterially to Peter, who echoes the gesture, pointing to his future self at the seashore taking the coin from the fish’s mouth. In the final episode, Peter appears for a third time in the right foreground, wearing the papal colours of blue and yellow signifying his role as the founder of the Church on earth, as he places the shekel for the Temple tax in the hand of the tax collector.

By creating the illusion of three dimensional space on a two dimensional surface, articulating form through the modulated fall of light, and using perspective and gesture to sequence the viewer’s reading of the picture, Masaccio gives a complete account of the Gospel narrative, from the arrival at Capernaum and the tax collector’s question to Peter, ‘Does not your teacher pay the tax?’ (v.24) to its conclusion in the payment of the tribute. And through these same devices the psychological drama of the miracle—Christ’s command that Peter must pay the tax—is acted out with arresting naturalism.

References

Ahl, Diana Cole. 2002. ‘Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel’, in The Cambridge Companion to Masaccio, ed. by Diana Cole Ahl (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 138–57

Strehlke, Carl Brandon. 2007. ‘The Brancacci style and the Carmine style’, in The Brancacci Chapel: Form, Function, and Setting, Acts of an International Conference, Florence, ed. by Nicholas A. Eckstein (Florence: Leo Olschki), pp. 87–114

George Hayter :

Saint Peter Paying the Tribute with a Piece of Silver Found in a Fish, 1817 , Oil on canvas

Unknown German or North Italian Artist :

The Tribute Money, c.962–68 , Ivory

Masaccio :

The Tribute Money, 1426–27 , Fresco

Catching Meaning

Comparative commentary by Geoffrey Nuttall

The meaning of this short passage from Matthew’s Gospel remains a subject of debate. Its context is the tax of a half shekel levied on each person entering Capernaum, as a contribution towards the upkeep of the Temple in Jerusalem. It begins with the encounter between the tax collectors and Peter, who at the outset accepts that Christ will pay it. Peter then goes to Christ, who responds by asking his opinion on whether the sons or the subjects of earthly rulers should pay toll and tribute to their king, to which Peter replies that only the subjects need do so. Christ agrees, saying that the sons of the kings are ‘free’, and it is implicit in his response that He, as the son of God, is also ‘free’ of the obligation to pay the tax.

These exchanges are told in the first three verses of the passage (vv.24–26), which concludes in the fourth (v.27), where Christ, despite not needing to pay the tax, nevertheless will pay it in order to avoid causing offence, presumably to the authorities in Capernaum, or to the Temple in Jerusalem, or both.

Unlike Christ’s other miracles, there is, to put it colloquially, a ‘so what?’ quality to the miracle of the Tribute Money, and Christ’s willingness to compromise for the sake of not giving offence is disquieting. To explain this, commentators from St Thomas Aquinas (Newman 1841: 616–20) to Bishop Hugh Montefiore (2009) have constructed elaborate arguments, rooted in the character of Peter, the relationship between church and state, and the social and legal conventions of first-century Judaea, though none has received universal acceptance.

The passage’s elusive meaning, however, does make it a pliable subject for the relatively few patrons who have used it as a metaphor for their own experience, as exemplified in George Hayter’s idiosyncratic reading. But the main reason it has proved to be one of the less popular of Christ’s miracles in the visual arts is almost certainly the challenge that the passage’s total lack of dramatic or emotional content presents to the artist. The text comprises a sequence of questions and answers that conclude with Christ telling Peter to take the shekel from the fish’s mouth. The action, taking place somewhere in Capernaum and in Peter’s house, is static and involves only Peter, the tax collectors, and Christ.

Hayter, unconcerned with theological debate, focuses on the dramatic conclusion of the story rather than a learned interpretation of the text. This is the moment when Peter, still clutching the dead fish, delivers the coin to the tax collector. Hayter also enlivens the scene by including Christ, Matthew, and another disciple, not present in the biblical account.

The anonymous carver of the Magdeburg tablet also introduces witnesses, not present in the text. However, he links Christ’s command, in verse 27, with its consequence, the finding of the fish, through the simple artifice of having Peter face Christ to receive his instruction, whilst his body executes it.

Masaccio keeps faith with biblical narrative, but still invests the composition with extraordinary emotional intensity, enacted within a convincing three-dimensional space. He brings the tension of the encounter between Peter and the tax collector to life, fusing this scene with the meeting of Christ and Peter that followed. He animates their dialogue through expression, gesture, and colour, and heightens the sense of drama by introducing an audience of carefully individualized and critically attentive disciples. Though silent, the words spoken by the tax collector, by Peter, and by Christ are ‘heard’ at the edges of the fresco, in the finding and the payment of the shekel, as Peter reappears multiple times in the time and space Masaccio’s genius has created.

References

McEleney, Neil J. 1976. ‘Who Paid the Temple Tax? A Lesson in the Avoidance of Scandal’, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 38: 178–92

Montefiore, Hugh. 2009. ‘Jesus and the Temple Tax’, New Testament Studies, 11.1: 60–71

Newman, John Henry. 1841. Catena Aurea: Commentary on the Four Gospels Collected out of the Works of St Thomas Aquinas, vol. 1, St Matthew, part 2 (John Henry Parker, Oxford and J. G. F. and J. Rivington, London)

Ottenheijm, Eric. 2014. ‘“So the Sons are Free”: The Temple tax in the Matthean Community’, in The Actuality of Sacrifice, Past and Present, ed. by Alberdina Houtman et al. (Leiden: Brill), pp. 71–88

Commentaries by Geoffrey Nuttall