Mark 12:38–44; Luke 20:45–21:4

Widow’s Mite

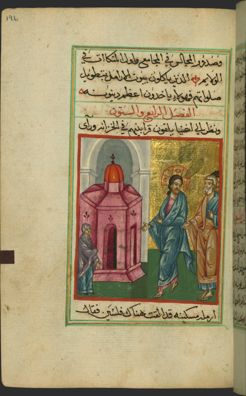

Ilyas Basim Khuri Bazzi Rahib

The Widow’s Offering, from an Arabic manuscript of the Gospels, c.1684, Ink and pigments on laid paper, 160 x 110 mm, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; W.592.196A, The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

An Offering So Small

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

This illumination belongs to an Arabic manuscript of the four Gospels. The text is written in naskhī, a form of Islamic calligraphy that is still used today to copy the Qur‘an. The manuscript was produced in Egypt under Ottoman rule, when Coptic Christians—members of one of the oldest continuous forms of Christianity in the world—had become a significant minority in a majority-Muslim country.

The dominant figure in the illumination is not the widow but Jesus, captured in the act of commending the woman’s generosity to two of his disciples. The disciple with the grey beard is likely to be Peter; the one peeking out from behind Peter may be the evangelist Mark, who is typically brown-haired and bearded in Byzantine art. The widow is tiny; it’s easy to miss her at first, off to the left side, dwarfed both by the church and by Jesus.

In depicting these disparities in size the illuminator was using a common artistic technique designed to magnify the importance of Christ and the Church, but the effect is to emphasize the widow’s vulnerability: just as she has so little to give in purely financial terms, she herself is so little.

The illumination reimagines the widow’s offering in the context of Christianity: the widow gives not to the Temple, but to the Church. In front of the large grey arch in the background is a small pink eight-sided building, probably a baptistery of the sort that were often positioned just outside cathedrals. Many baptisteries were eight-sided to symbolize the day of the resurrection as an ‘eighth day’—the first day of a new week, or seven days plus one—the dawn of the new creation.

The illumination thus considers the widow’s offering in a larger scriptural narrative. Here the focus is not on her generosity, but on baptism, salvation, and the arriving eschaton (God’s new age).

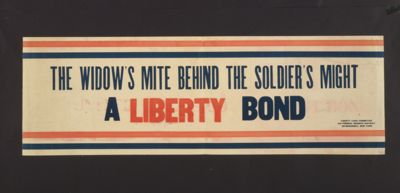

Unknown American artist

The Widow's Mite Behind the Soldier's Might—A Liberty Bond, 1917, Lithograph, 250 x 750 mm, Library of Congress, Washington DC; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, LC-USZC4-8355

A Tale of Two Treasuries

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

This war poster plays on the familiarity of the phrase ‘the widow’s mite’. The word ‘mite’ is the English translation of the widow’s offering in the King James Version, which in 1917 was still the dominant translation used in the English-speaking world.

Shortly after entering the First World War in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson endeavoured to ‘sell the war to a sceptical American public’ (Noble, Swaney, Weiss 2017: 9), in part through the Division of Pictorial Publicity (DPP). The DPP recruited ‘many of the nation’s best artists’—more than 300 of them—'to create posters for every facet of the war effort’, including posters urging Americans to buy Liberty Bonds, which were issued to support the Allied forces during WWI (ibid: 10). The DPP printed millions of posters designed to convince Americans that it was their patriotic duty to buy the bonds.

One poster designed by artist Frederick Strothmann declared, ‘Beat back the Hun with Liberty Bonds’, and featured a grim German soldier holding a sword dripping with blood (Kang & Rockoff 2015: 51). In another poster by artist C. R. Macauley, the Statue of Liberty points sternly at the viewer alongside the words, ‘YOU buy a Liberty Bond lest I perish’. The selling of Liberty Bonds eventually raised seventeen billion dollars for the United States war effort.

This particular poster uses the story of the widow’s offering to evoke the noble act of giving sacrificially to a good cause—not to the Temple, as in the Gospel accounts, but to the United States Treasury. The poster emphasizes that even the smallest contribution (symbolized by the ‘mite’) added to the might of the Allied soldiers. Strong, straight lines in red, white, and blue evoke the American flag. No possibility is entertained here that these contributions might end up being ‘devoured’ (Mark 12:40) in the service of a devouring war, rather than used for some better good.

References

Kang, Sung Won, and Hugh Rockoff. 2015. ‘Capitalizing Patriotism: The Liberty Loans of World War I’, Financial History Review, 22.1: 45–78

Noble, Aaron, Keith Swaney, and Vicki Weiss. 2017. A Spirit of Sacrifice: New York State in the First World War (Albany: Excelsior Editions)

James Tissot

The Widow's Mite (Le denier de la veuve), 1886–94, Opaque watercolour over graphite on gray wove paper, 183 x 281 mm, Brooklyn Museum; Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.211, Bridgeman Images

All She Had Left to Give

Commentary by Rebekah Eklund

James Tissot (1836–1902) sought to reproduce as faithfully as possible ‘the physical appearance of Palestine and its people’ (Chu 2010). After Tissot converted to Christianity, he travelled to Egypt, Syria, and Palestine to visit the sites of Christ’s life. This painting is part of his famous Life of Christ series, which reimagined scenes from the Gospels. The series was so popular with American audiences that selections from the series ‘remained on almost continuous display for more than thirty years’ in the Brooklyn Museum in New York (Parks 2010: 91).

In this Gospel scene, a wealthy man (at the centre of the painting, though in the background) drops his gift into the Temple’s box. The widow who has just donated her last two pennies commands the foreground of the scene; she seems almost on the verge of stepping into the viewer’s space. But her gaze is directed downwards, avoiding all eye contact, as she hurries away. Almost nobody is looking at the rich man. Most of the onlookers, including Jesus and two of his disciples at the left of the painting, watch the woman as she departs. Jesus gestures toward her with approval, commending her generosity.

Only one disciple (at the far left, in the white cap) seems instead to be staring at the rich man. Perhaps this is Judas, who is accused of stealing from the disciples’ common purse (John 12:6) and who betrays Jesus for thirty pieces of silver (Matthew 26:15).

The two more hostile-looking men at the right of the painting are perhaps scribes—teachers of the law who were associated with the Temple. Just before the scene depicted here by Tissot, Jesus condemns the scribes, saying, ‘They devour widows’ houses’ (Mark 12:40). Tissot has, unusually, depicted the widow as a young woman with a small child, highlighting her vulnerability: both are dependent on the kindness of men such as these.

References

Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate. 2010. ‘James Tissot: “The Life of Christ”: Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, New York’, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, 9.1

Parks, John A. 2010. ‘The Watercolor Bible: Tissot’s “Life of Christ”’, American Artist: Watercolor, 16.62: 88–95

Ilyas Basim Khuri Bazzi Rahib :

The Widow’s Offering, from an Arabic manuscript of the Gospels, c.1684 , Ink and pigments on laid paper

Unknown American artist :

The Widow's Mite Behind the Soldier's Might—A Liberty Bond, 1917 , Lithograph

James Tissot :

The Widow's Mite (Le denier de la veuve), 1886–94 , Opaque watercolour over graphite on gray wove paper

Obligations to Give

Comparative commentary by Rebekah Eklund

In the Gospels of Mark and Luke, the story of the widow who gives her two small copper coins to the Temple’s treasury comes immediately after Jesus’s warning about the scribes who ‘devour widows’ houses’ (Mark 12:40; Luke 20:47). This arrangement is not accidental. The scribes were closely associated with the Temple; their living came directly out of that very treasury. When the disciples watched the widow giving ‘everything she had, all she had to live on’ (Mark 12:44), Jesus’s warning was still ringing in their ears; surely they must have wondered whether this was one of the widows whose house had been devoured by the very Temple to which she humbly gave.

This is a story with an edge. It is not only about the beauty of sacrificial generosity, but a condemnation of the system that left the widow with so little to give.

Of the three artworks in this exhibition, Tissot’s watercolour is the only one to capture this sharp edge. The wealthy man, in his long robe, could represent both the ‘many rich people [who] put in large sums’ (Mark 12:41) and ‘the scribes, who like to walk around in long robes’ (v.38). The woman looks especially vulnerable in Tissot’s painting—her eyes cast down, her arm firmly cradling her son as she hurries away. Even her baby has his eyes downcast, his face partially hidden from the viewer. Tissot has painted her not as an elderly widow but a young woman with a small child to support, a particularly vulnerable position in a patriarchal society.

The woman is the primary focus in Tissot’s painting, whereas in the Arabic manuscript the dominant figure is Christ. The tiny size of the woman in the illumination in the seventeenth-century manuscript Anājīl renders her vulnerable in a different way. Like the widow in Tissot’s painting, she is off-centre—so much so that she is easy to miss at first, even though the Gospel narrative is ostensibly about her. Her tiny size may originally owe itself to artistic conventions that used scale to emphasize the comparative importance of Christ and the saints. Yet, viewed today, her smallness seems to further de-centre her; this is a story not about her but about Christ’s approval of her generous offering. The object of her generosity is not the Temple, as in the Gospel accounts, but the Church, represented by the octagonal pink baptistery. The illumination contains no hint of Jesus’s criticism of those who devour the houses of widows. No scribes or wealthy men appear in the illumination, further muting the context of condemnation. This widow represents every Christian who gives generously to the Church.

In the Liberty Bond poster, the object of generosity is neither Temple nor Church but the United States government and its treasury. The ‘widow’ is every American citizen who gives even a small amount to the war effort. The Liberty Bonds were part of Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo’s policy of ‘capitalizing patriotism’ (Kang & Rockoff 2015: 45). A well-known story of a widow’s costly generosity to a religious institution is transmuted boldly into an exhortation to give to a government’s war effort.

For first-century Jews (as in Tissot’s rendering) and later Christians (as in the Arabic manuscript’s illumination), giving to God—and to the poor—was a sacred obligation, one mandated in Scripture. (The Muslim neighbours of the Coptic Christians who produced the Arabic manuscript would have affirmed this emphasis on holy almsgiving.) The Liberty Bond poster smoothly elides the Church’s tithes with the government’s treasury: a striking example of civil religion, in which the state stands in for a religious entity.

Collectively, the three artworks demonstrate the flexibility of the widow’s story; she can represent anyone who gives humbly and sacrificially to a perceived greater good. In the case of the war poster, the greater good was an ambiguous one: even the American public needed convincing. In Mark’s account, the widow’s gesture is profoundly multi-layered: while Jesus admires her generous act, his earlier criticism of those who devour the livelihoods of widows requires us to wonder why she had so little left to give. A central obligation of Temple and Church, as well as of civil society, is to use their resources to care for those who are vulnerable, like the widow. These artworks, and the widow’s story, invite us to consider that obligation.

References

Kang, Sung Won, and Hugh Rockoff. 2015. ‘Capitalizing Patriotism: The Liberty Loans of World War I’, Financial History Review, 22.1: 45–78

Commentaries by Rebekah Eklund