1 Kings 3–4

The Wisdom of Solomon

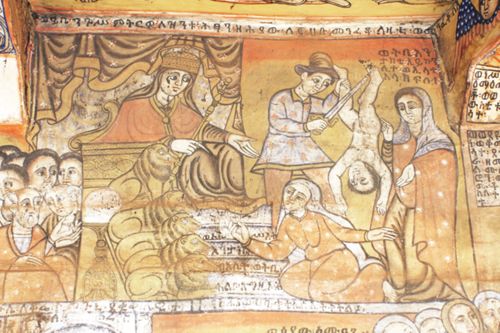

Unknown Ethiopian artist

The Judgement of Solomon, Late 19th century, Mural, Church of Dabra Marqos, Goggam, Ethiopia; Photo © Michael Gervers, 2008

An Ethiopian Perspective

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

Ethiopia’s fourteenth-century national epic, the Kebra Nagast (‘The Glory of the Kings’) which expands and enhances the biblical story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, detailing how their son Menelik I became the first king of Ethiopia, is a key text in the Ethiopian Church. Not surprising, then, that, through the centuries, episodes from Solomon’s life have become an important and regular feature in the Church’s rich iconography.

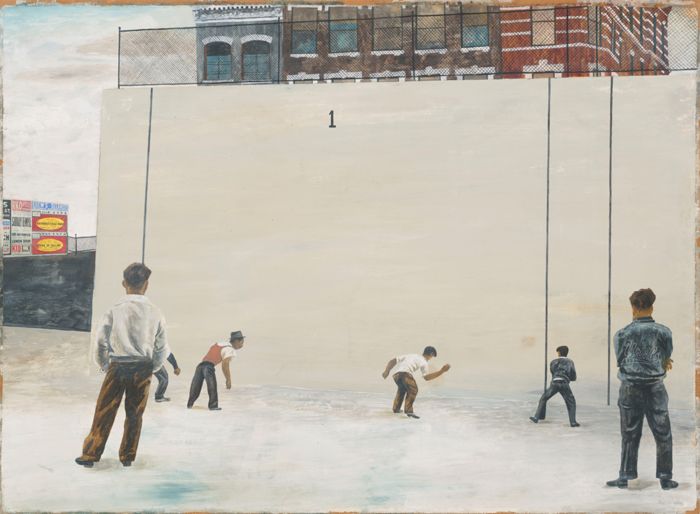

The Church of Dabra Marqos, Goggam, has two large murals depicting first, Solomon’s sacrifice and dream at Gibeon (1 Kings 3:4–15), and second, the test of his wisdom (vv.16–28), which we see here. The composition is structured according to three groupings. In the centre, a young Solomon, sceptre in hand, sits on his throne, the approach to which is guarded by lions that defend the king (after 1 Kings 10:19). To the left, alarmed bystanders crowd together, making their own assessment of what they see. But it is the scene on the right that attracts the attention of everyone—the bystanders, Solomon, and even the lions. There, the larger-than-life child is about to be cut in two by the king’s servant with the approval of the false mother while the true mother pleads with the king.

This arrangement of figures offers quite a distinctive approach when compared with Western iconography. First, given the size of the child, it is clear that the servant cannot carry out his task—it can only be accomplished if the false mother helps hold the child for him, something her hand gestures seem to suggest she is prepared to do. The true mother is the only person who faces away from the child, perhaps suggesting her selflessness and altruism as she offers to part with her son to save his life. Most noteworthy of all, is the compassion of the youthful king as he bends forward with arms outstretched.

Even though the subject of the mural is perfectly recognizable to a biblically-literate viewer, the accompanying inscriptions in Amharic describe the story and, in particular, cite the dialogue of the two women almost verbatim. The artist is unknown but the context suggests that this work was intended to encourage the church’s congregation, here depicted as bystanders, to reflect on the wisdom of a king who, many centuries before, had been appropriated with much love and affection into Ethiopian culture and tradition.

References

Witakowski, Witold and Ewa Balicka-Witakowska. 2013. ‘Solomon in Ethiopian Tradition’, in The Figure of Solomon in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Tradition: King, Sage, and Architect, ed. by J. Verheyden (Leiden: Brill), pp. 219–40

Nicolas Poussin

The Judgement of Solomon, 1649, Oil on canvas, 101 x 150 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris; Collection of Louis XIV (acquired in 1685), Inv. 7277, Photo: Stéphane Maréchalle, © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Justice or Compassion?

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

The drama, suspense, and anguish that lie at the heart of the biblical description of the first test of Solomon’s wisdom as he judges between the competing claims of two mothers (1 Kings 4:16–28) have proved irresistible to artists. Nicolas Poussin focusses the viewer’s attention on a shocking and very cruel moment in the story—immediately after Solomon’s first verdict that the living child be cut in two (v.25) but before his second verdict that he should be given to his real mother (v.27).

Apart from the false mother and the king’s adviser to Solomon’s left, whose expressions indicate that they agree with his verdict, all the other bystanders show varying degrees of rejection and horror. Poussin uses hand gestures to register shock and disapproval, most noticeably in the raised hands of the true mother and of the bystander mother in blue on the far right. Even the awkward angle of the soldier’s arm as he draws his sword to kill the child indicates his reluctance.

Solomon sits above the entire fray, cold, detached, and expressionless, his unbiased judgement underlined by the remarkable symmetry of the entire setting.

Poussin also includes an allusion to Solomon’s second verdict—that the child be given to his rightful mother—by the position of the two children. He places the dead child in the arms of the false mother (in contrast to iconographical convention which normally places him between the two women) while the living child looks ready to fall into his real mother’s open arms, once the harsh first judgement has been rescinded.

The story concludes that ‘all Israel stood in awe of the king’ (v.28) because of the wisdom of his judgement. But, in focussing on this precise moment in the story, Poussin asks us to reflect (like the bystanders in his painting) on how Solomon’s initial judgement appears indifferent, harsh, and inhuman, even though on the surface it seems impartial and fair, and how the real hero of the story is not, in fact, the wise king but rather the mother who, through her compassion and selflessness, has saved the child. The story—as expressed through Poussin’s painting—is not only about justice but also about mercy.

References

Bätschmann, Oskar. 1990. Nicholas Poussin: Dialectics of Painting (London Reakton), pp. 80–81

Cooke, Peter. 2016. Painting and Narrative in France from Poussin to Gauguin (Abingdon: Routledge), pp. 194–95

Plett, Heinrich F. 2004. Rhetoric and Renaissance Culture (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 334–46

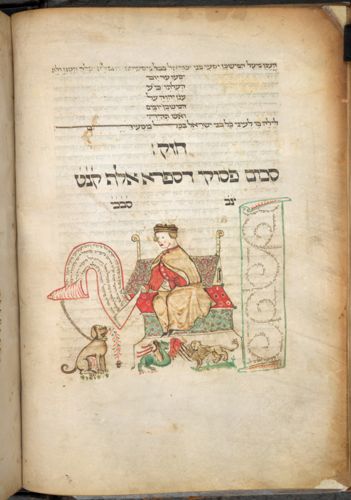

Unknown German artist

A Scholar (King Solomon ?), from the Coburg Pentateuch, c.1390–96, Illuminated manuscript, 180/175 x 135 mm, The British Library, London; Add MS 19776, fol. 54v, © The British Library Board (Add MS 19776, fol. 54v)

Sage and Naturalist

Commentary by Martin O’Kane

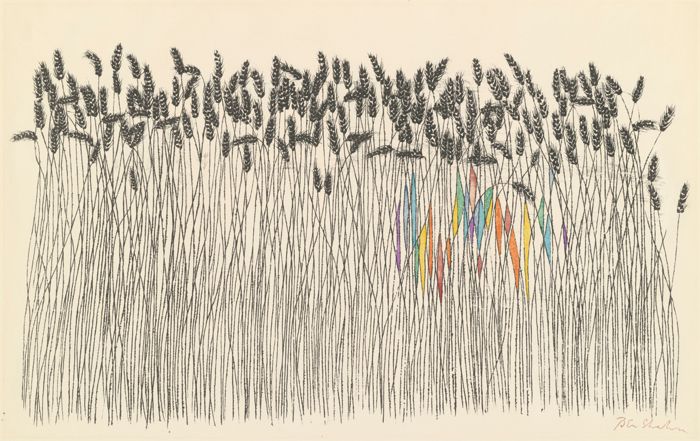

That Solomon had two named secretaries and a recorder among his very highest officials (1 Kings 4:3), that he composed numerous proverbs and songs (4:32), and is credited with the authorship of several biblical books (Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes) has been much celebrated, particularly in Jewish culture. Furthermore, his encyclopaedic knowledge of the natural world—trees, animals, birds, reptiles, and fish (1 Kings 4:33)—spawned many imaginative legends both in Jewish and Islamic folklore.

An exquisite miniature—one of only three—in the Coburg Pentateuch combines these two distinctive aspects of Solomon’s character (although he is not named, it is generally agreed that the figure’s attributes identify him as none other than Solomon). In this manuscript—which also includes sophisticated grammatical treatises on Hebrew punctuation—the figure of Solomon is flanked by two large scrolls inscribed in Hebrew which represent the books of Exodus and Leviticus. His elaborate throne is decorated in floral motifs, with animals at his feet (a lion and what seems to be a griffin).

The king examines one of these learned texts—held in his right hand and conveniently secured at the other end to the collar of his dog—which consists of a compilation and juxtaposition of biblical verses containing the Hebrew word Ohel, ‘the tent of meeting’ (created for Moses’s encounters with God) with which the book of Exodus is much concerned (Exodus 28–39). The scroll on the left contains a compilation of verses containing the Hebrew word Vayiqra (‘and he called’) which opens Leviticus and is the name given to the entire book in Jewish tradition (Leviticus 1:1).

That Solomon should appear among the most sacred of Jewish scriptures and engage with them in such a learned manner reflects the tradition, emanating from 1 Kings 4, that Solomon applied his wisdom to literary pursuits and, in particular, to the dissemination of the Torah: according to the midrash (Exodus Rabbah 15.20) he is reputed to have built synagogues and centres of learning in which the Torah was studied by himself, by a multitude of scholars, and even by young children.

That the miniaturist should combine this aspect with the tradition of Solomon’s engagement with, and control over, the natural world, highlights the detailed attention given to these attributes of the biblical Solomon in Jewish and Islamic tradition—attributes that remained much less developed in Christian culture and iconography.

References

Narkiss, Bezalel. 1969. Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts (New York: Macmillan), p. 114

Unknown Ethiopian artist :

The Judgement of Solomon, Late 19th century , Mural

Nicolas Poussin :

The Judgement of Solomon, 1649 , Oil on canvas

Unknown German artist :

A Scholar (King Solomon ?), from the Coburg Pentateuch, c.1390–96 , Illuminated manuscript

Solomon in Shared Tradition

Comparative commentary by Martin O’Kane

1 Kings 3–4 sings the praises of Solomon’s unsurpassed wisdom: how he acquired it supernaturally in a dream (3:5–14); how it enable him to act judiciously in the rather bizarre case of the two mothers (3:16–27); how it bestowed on him outstanding literary skills (4:3, 32), and equipped him with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the natural world, including animals and fish (4:33).

Commentators have been less fulsome in their praise of the king. Several Jewish exegetes, such as fifteenth-century commentator Isaac Abarbanel, argue that Solomon’s request for a sword to induce the real mother to step forward through compassion shows no extraordinary brilliance or foresight on the part of the king. Equally, some deemed Solomon’s literary achievements (4:32) to be quite modest, given his much-vaunted creative talents. Indeed, the medieval commentator David Kimchi (1160–1235) suggested that we no longer have Solomon’s complete oeuvre because much of it must have been lost during the period of the exile, only the finest of his compositions managing to survive.

Artists, too, were sensitive to some unsettling aspects of the narrative, and this is especially so in representations of Solomon’s judgement in the case of the two women. It is a subject that has become one of the most painted in the entire repertoire of European art. In The Judgement of Solomon, Nicolas Poussin focusses our thoughts on a very precise single moment in the story when Solomon passes his first judgement, that the child be cut in two (1 Kings 3:24–25), the moment of highest tension. For Poussin, Solomon’s harsh judgement may be totally impartial (perhaps conveyed by the painting’s very precise symmetry) but, at the same time, he wants us to reflect on how cruel and inhuman Solomon’s very suggestion is: is it a judgement devoid of any mercy? The range of emotions clearly felt by the bystanders who behold the unfolding scene prompts the viewer to question the king’s first verdict. When the second judgement is uttered—that the child be given to its true mother—it is the quality of the woman’s compassion (an aspect overshadowed in the narrative which is interested only in promoting Solomon’s judicial skills) that clearly wins the day for Poussin.

The representation in the Goggam mural was intended for the worshipping congregation of a small church in Ethiopia. Until the death of Haile Selassie in 1975, it was the belief that all emperors of Ethiopia were direct descendants of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Not surprising, then, that the young Solomon in the mural is depicted as a compassionate ruler, while the captions and the exchanges between the two women (written in Amharic), together with the familiar attire of the characters, all suggest to the viewer that the first proof of Solomon’s supernatural wisdom actually occurred within their own country and among their own people (represented by the group of bystanders in the mural). The mural, therefore, not only encouraged its intended viewers to look afresh at a well-known biblical story but it also appealed to, and confirmed, their sense of national identity.

The Coberg Pentateuch illumination reflects the importance given to Solomon in Jewish midrashic literature as a prototype of the Talmudic sage—one who is able to analyze and justify the reasons for the commandments of the Torah. But it has wider significance, too, in that it illustrates the shared cultural (and visual) traditions concerning Solomon in Judaism and Islam. A Jewish tradition, recorded by Rashi (Commentary on 1 Kings 3.15), describes how, after Solomon awoke from his dream (1 Kings 3:15) he would hear a bird chirp or a dog bark and he would understand its language, while the Qur’an (Surah An-Naml 27:15–16) claims that after Solomon received supernatural wisdom, he was taught the language of the birds. In Jewish and Islamic art, Solomon is frequently depicted, surrounded by animals, birds, spirits, and demons, illustrating his remarkable wisdom that allowed him to converse with all aspects of the natural world (O’Kane 2017).

The Coberg miniature reflects this shared iconographical tradition in the way it includes different species—mythical and real, flora and fauna (note the detail of the dog bringing along a plant for Solomon’s inspection). While Christian commentators generally interpret the accounts of Solomon’s wisdom simply as prefiguring the wisdom of Christ in the New Testament (summed up in the advice given in Matthew 6:33), Jewish and Islamic perspectives—both textual and visual—can offer us alternative perspectives on the character of Solomon, making him a more personable and engaging figure, as this remarkable illumination demonstrates.

References

O’Kane, Martin. 2017. ‘Painting King Solomon in Islamic and Orientalist Tradition’, Bible in the Arts, pp. 1–20 <https://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Bibelkunst/BiKu_2017_06_OKane_Solomom_Islamic_Tradition.pdf> [accessed 1 June 2021]

Commentaries by Martin O’Kane