Genesis 3:1–13

The Fall

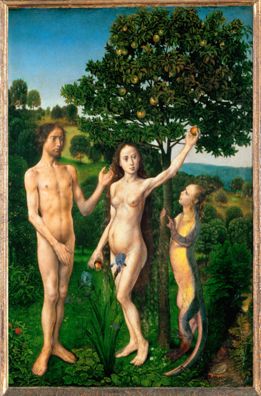

Hugo van der Goes

The Fall, Adam and Eve Tempted by the Snake, from the Diptych of the Fall and the Redemption, left wing, c.1470, Oil on oakwood, 33.8 x 23 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; inv. 945, Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

An Almost Casual Transaction

Commentary by Michael Glover

There is a curious parity—of height and even of seeming importance—amongst the three protagonists (Adam, Eve, and the serpent, depicted as a woman-cum-salamander) in this painting by a Flemish master of the sixteenth century.

The painting itself is the left-hand wing of a diptych, so this panel serves as a contribution to a larger visual conversation. It does not have to be self-sufficient in its depiction of the tragedy in the way that single works representing the whole narrative have to be. There is not the same pressure of anxiety to capture the full psychological momentousness of what is underway.

See how the composition edges away into a benign pastoral scene, for example. You could even therefore regard it as gently inclining towards the more casually anecdotal. The salamander with a woman’s face and long hair (though not as long as Eve's) is not part-hidden from view or even 'subtil' (crafty) as the King James Bible has her (3:1). She is not at all—not yet—some malign, earth-creeping, squirmily perverse thing. In fact, rearing up and made to look part human, she seems almost guilelessly curious as to the outcome. Her she-ness is of great significance, of course (though not in the text of Genesis). It points to the notion—so widely-assumed in Christian tradition—that woman was the source of all our anguish in leading Adam astray.

In common with the vast majority of other depictions, the fruit plucked from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is an apple—though it is merely described as a fruit (any fruit will do) in the Bible (vv.3, 6). Eve, face forward, reaches back fairly casually, arm fully extended so as to allow us to admire its twisting musculature as it gleams white against the dark green background. Adam, though covering his genitals, looks little more engaged. He is ready to accept what is being offered, qualmlessly. Something is happening here, but perhaps it is not too much beyond the usual run of things out here in the hilly, bosky, all-too-familiar out of doors...

Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens

The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, c.1615, Oil on panel, 74.3 x 114.7 cm, The Mauritshuis, The Hague; inv. 253, Scala / Art Resource, NY

A Last Look at Innocence

Commentary by Michael Glover

This collaborative work from relatively early in the seventeenth century shows us a moment of almost joyous loveliness and optimism before the tragedy strikes. This is paradise, lush and wooded, beneath a cheerful sky, frozen in the instant before it turns to paradise no longer.

What a creation this is!

The composition opens up a huge vista of great natural abundance, and the serpent seems to be assisting a liberal apple harvest. Yet this is a genuinely malevolent serpent—coiled round and round the bough of the tree—whose gift of apples to Eve happens almost covertly, from the fly space above this natural stage. A horse looks on, raising a hoof and flaring its nostrils in what may be warning, while a white rabbit—symbol of an innocence and purity to be forever lost?—plays at Adam’s feet.

Eve shows no alarm. Adam looks in no way apprehensive or troubled. It is the teeming, colour-splashed landscape with all its natural life—peacock, ostrich, tiger, and much else—which so preoccupies and beguiles, painted by an artist celebrated for his natural history painting.

Adam and Eve are unashamedly naked (no need for a fig leaf, not yet), and they are surrounded by many of the animals, fish, and fowls of the air that might have been found in paradise, living in a state of blessed harmony, one with another. In the left foreground, for example, is the Bird of Paradise herself, maitre d’ of the scene, a creature unseen in Europe until the sixteenth century (de Rynck 2009: 31).

One detail has an especially poignant theological resonance. Above Adam's head hangs a bunch of grapes, an allusion (it would seem) to the blood that will be shed in payment for this transgression, and of the Eucharist, when it will be drunk to remedy sin’s enduring consequences.

References

de Rynck, Patrick. 2009. Understanding Paintings: Bible Stories and Classical Myths in Art (London: National Gallery)

Titian

Adam and Eve, c.1550, Oil on canvas, 240 x 186 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; P000429, Copyright of the image Museo Nacional del Prado / Art Resource, NY

An Ominous Push-and-Pull

Commentary by Michael Glover

Titian brings touches of drama and sensuality to this scene of the serpent’s gift of the fruit. The serpent itself has been anthropomorphized to such an extent that he looks like the sort of charming, puff-cheeked putto who might adorn the upper corner of an altarpiece. He is also actively involved in his own treachery in so far as he reaches down from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and hands Eve what is here shown as an apple. The scene is dark and ominous—see how clouds seem to be gathering as if expressive of divine displeasure. The tree itself is massive, and stands centrally, with the two figures of Adam and Eve organized with a pleasing degree of visual symmetry to left and to right of it.

Titian emphasizes the fleshly appeal of Adam and Eve. The seated Adam is handsome and ruggedly built, muscular, with a tousling of black hair. Eve stands and faces us. Her naked body is splashed with light from goodness knows where in order to enable the viewer to admire and revel in it all the more. Their genital coverings are substantial and lush, and remind us more generally of fecundity.

Adam himself plays a dramatic role. In a departure from the text—which has him happily accede to the fruit—he pushes back against Eve, as if trying to prevent her from doing the baleful deed; as if mindful of its universal consequences for humankind for evermore.

And just to the left of Eve’s right heel, there is a fox peeking out—a fox, an animal both unclean and—as in the fables of Aesop—wily.

Hugo van der Goes :

The Fall, Adam and Eve Tempted by the Snake, from the Diptych of the Fall and the Redemption, left wing, c.1470 , Oil on oakwood

Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens :

The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, c.1615 , Oil on panel

Titian :

Adam and Eve, c.1550 , Oil on canvas

‘A Tree To Be Desired’

Comparative commentary by Michael Glover

[T]he woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise. (Genesis 3:6 ESV)

The difficulty facing all artists who have risen to the challenge of this pivotal moment in the biblical story has been how to put flesh on its bones. It is a chapter which largely consists of two bald and almost disembodied conversations. A voice which Christian tradition comes to associate with supreme malignity addresses a listener who was evidently seduced by the overwhelmingly juicy appeal of what she saw.

Each painting in this exhibition speaks resoundingly of its time, its historical moment, and its place of facture. The Flemish painter Hugo van der Goes shows us an Adam and Eve of a customary northern European stamp, naked but scarcely alluringly so. This is humankind with all its unidealized foibles, and relatively emotionless. Flesh is little more than a covering for bones. The human forms are little warmer or more animated than puppets. The ‘fig leaf’ that covers Eve’s private parts is of studied symbolic interest: it is an iris, symbol of purity (de Rynck 2009: 26).

Titian’s covering of our parents’ genitals is a roaring extension of the natural abundance to be found elsewhere in this painting. By contrast, Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, in their telescoping of two quite distinct historical moments—God's populating of the Garden of Eden with Eve's later temptation—have chosen to show their bodies in all their naked innocence. The imminent knowledge of that nakedness will cause them an embarrassment so acute that they feel obliged to hide it away from the world.

In the case of Titian's depiction of the pair, a new bodily sensuality has entered in, in part to do with the idealising tendencies of the Renaissance (though the painting may also act as a reminder to us that Titian lived in warmer, more southerly climes than his Netherlandish counterparts). In this and the work by Brueghel and Rubens, there is more attempt to show some emotional electricity between Adam and Eve. Each seems to care about and attend to what the other is doing.

All three paintings show us the unboundedness of local landscape rather than the boundedness of a garden whose custodian, chief worker, and vicegerent Adam is said to have been. Rubens and Brueghel allude more closely to the biblical description of the Garden of Eden, with its trees, its wildlife, and its four rivers (though only one is shown here).

The representation of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in these three paintings is a perpetual source of delight and bemusement. In the earliest painting, by van der Goes, we are shown an apple tree of a fairly customary shape and size, depicted with a high degree of accuracy. Though doughty looking, it is also relatively thin and spindly. Titian’s tree is much more solid, massy, and physically substantial (in fact, somewhat akin to Titian’s general representation of the human form), and certainly wholly unlike any other apple tree we may have chanced upon. The tree in the third painting, by Rubens and Brueghel, seems to be hedging its bets by disguising its true nature behind an abundance of foliage. What we are made aware of most of all is the fact that this tree does not limit itself to the bearing of apples. Call this one a multi-fruit-bearing miracle tree then, a one-off amongst God's creations.

In these various interpretations, the tree (like the story at whose heart it stands) is both a symbol-laden bearer of mythic meaning, and something that without evasion reflects the truth of our world.

References

de Rynck, Patrick. 2009. Understanding Paintings: Bible Stories and Classical Myths in Art (London: National Gallery)

Commentaries by Michael Glover