John 5:1–18

The Pool of Bethesda

William Hogarth

Christ at the Pool of Bethesda, 1735–36, Oil on canvas, 416 x 618 cm, St Bartholomew’s Hospital Museum and Archive; Presented by the artist, 1737, SBHX7/7.1, Courtesy Barts Health NHS Trust Archives and Museums

Healing in the Hospital

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

The Pool of Bethesda is one of two biblical paintings that William Hogarth painted for London’s St Bartholomew’s Hospital (known as ‘Bart’s’) in the 1730s and which remain in the hospital’s collection (the other is The Good Samaritan, 1736–37).

Jesus’s healing miracles have long been subjects of works of art made for hospitals. Such artworks place the work of the hospital in a tradition of caring for the sick that follows the example of Christ.

Here, Hogarth depicts the sick at the pool of Bethesda suffering a variety of medical afflictions. There is a popular tradition that Hogarth modelled the figures on hospital patients. Although this idea is not verifiable, it speaks to the relevance of this subject to its location. Patients attending Bart’s might recognize their own conditions in the painting.

In Hogarth’s day, miracles were being called into question by critics such as Thomas Woolston, who published a series of six discourses on the miracles of Jesus in the late 1720s. As Ronald Paulson has argued in his comprehensive study of the artist, Hogarth himself seems to have understood the biblical miracles as allegory (Paulson 1992: 89–91). Whether viewers believed the biblical narrative to be fact or allegory, this image of healing could offer hope to the hospital patients that they might be ‘made whole’ (v.11)—something which may be no less true today.

At the start of the narrative, the sick man tells Jesus that he has no one to help him into the pool when the waters periodically become healing for the first person to enter the pool. Hogarth depicts the injustice of the fact that not all patients have access to the healing waters: in the background, a mother with a sick baby is being pushed away by the servants of a wealthy woman.

Today, Bart’s Hospital is run by the National Health Service, the universal healthcare system in the United Kingdom. Hogarth’s picture can say new things in this new context: all of the sick can receive treatment here, just as Jesus’s ministry was inclusive of individuals from all walks of life.

References

Paulson, Ronald. 1992. Hogarth, Vol. 2: High Art and Low, 1732–1750 (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press)

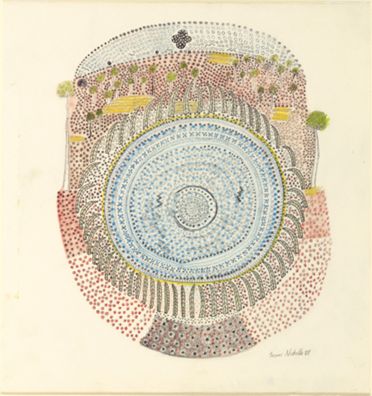

Trevor Nickolls

Drawing from the Bethesda series (Pool), 1987, Drawings, drawing in colour pencil and black fibre-tipped pen, 35.1 x 33.3 cm, The National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Purchased 1988, NGA 88.384, © Copyright Agency; Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2019; Photo: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra / Bridgeman Images

Dreamtime Healing

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

Trevor Nickolls (1949–2012) created his Bethesda series after suffering a car accident that damaged an eye, his arms, legs, and face. The artist produced a number of works in response to the accident, which were a form of catharsis, and meditation on the vulnerability of the body.

Nickolls was an Aboriginal Australian who grew up in Adelaide. His work reflects a variety of influences, including Aboriginal spirituality, the urban environment, and the Bible, as is the case in the Bethesda series. While Nickolls was not working from a Christian perspective, the story of the pool of Bethesda as a place of healing inspired the name of this group of drawings.

The five Bethesda drawings in the National Gallery of Australia depict a variety of subjects: landscape, trees, seated man, landscape with man playing didgeridoo, and pool. Pool has the most explicit connection to the biblical narrative.

A major theme in Nickolls’s oeuvre is ‘Dreamtime to Machinetime’. This is the artist’s phrase, devised to express the cultural transition that Aboriginal people have made from indigenous ways of life to urban environments. The Bethesda series seem to epitomize a Dreamtime of Nickolls’s own creation, depicting a land without urbanization.

In Aboriginal spirituality, every thing in the world is interconnected. People, animals, plants, land, and sky are all part of a larger reality, created by the Ancestors in Dreamtime. In the face of his brutal encounter with a machine, Nickolls seems to have sought healing in creating his own Dreamtime.

As a source of hydration and cleansing, as well as a place of tranquillity, a pool can be a symbol of healing that transcends individual religious traditions. The biblical Bethesda was a place where the unnamed man was ‘made whole’ through an encounter with Jesus (vv.11, 14, 15). Nickolls’s Bethesda is a Dreamtime place where he too sought to be made whole. As viewers, we can also seek wholeness through contemplating Nickolls’s Bethesda.

References

O’Ferrall, Michael (ed.). 1990. 1990 Venice Biennale, Australia: Rover Thomas–Trevor Nickolls (Perth: Art Gallery of Western Australia)

Emma Stebbins

Bethesda Fountain (The Angel of the Waters), 1868, Bronze, 8ft tall, Central Park, New York; Patti McConville / Alamy Stock Photo

Healing in the City

Commentary by Naomi Billingsley

The Angel of the Waters fountain sits in Bethesda Terrace in Manhattan’s Central Park. Designed by Emma Stebbins, it was built to celebrate the Croton Aqueduct, completed in 1842.

The limited fresh water on Manhattan Island was inadequate for the growing population. Worse still, the local water supply had become polluted and spread disease. The Croton Aqueduct brought safe water to New York City, and had a dramatic effect on public health.

Stebbins’s Angel of the Waters alludes to John 5:4—probably a later addition to the biblical text, and one which explains that the sick visited Bethesda because ‘an angel of the Lord went down at certain seasons into the pool, and stirred up the water; whoever stepped in first after the stirring of the water was made well from whatever disease that person had’. Stebbins’s Angel therefore invokes the idea of the angel of Bethesda as an agent of healing in order to celebrate the health benefits of clean water for the city.

The aqueduct is no longer in use, but the Bethesda fountain can continue to represent Central Park as a place of respite, and a green lung in the high-rise city that surrounds it. It is a public space in New York City, just as the pool of Bethesda was in Jerusalem. It speaks to Jesus’s ministry as indiscriminate in the way it reached out to all types and conditions of people.

The fountain, Bethesda Terrace where it sits, and Central Park around it, can be viewed as a modern incarnation of the sacred, public space of Bethesda; a place where Jesus’s ministry again can be enacted. This symbolism has been taken up in popular culture. As a public place for Jesus’s ministry, it appears in the film Godspell! (1973) as the site where John the Baptist baptizes disciples. As a place of healing, it is the setting for the final scene in Tony Kushner’s play about the 1980s AIDS epidemic Angels in America (1993).

Jesus’s healing of the infirm man in John 5 is described several times as making the man whole (vv.11, 14, 15); perhaps, under the gaze of Stebbins’s angel, the New Yorker or visitor can find wholeness in Central Park.

William Hogarth :

Christ at the Pool of Bethesda, 1735–36 , Oil on canvas

Trevor Nickolls :

Drawing from the Bethesda series (Pool), 1987 , Drawings, drawing in colour pencil and black fibre-tipped pen

Emma Stebbins :

Bethesda Fountain (The Angel of the Waters), 1868 , Bronze

Places of Healing

Comparative commentary by Naomi Billingsley

William Hogarth, Emma Stebbins, and Trevor Nickolls all engaged with John’s narrative of the man being healed at Bethesda in response to the specific contexts of healing in which their own work was situated. Hogarth was painting for a hospital, and he depicted the sick at the pool in the manner of hospital patients. Stebbins was designing a fountain to celebrate an aqueduct that brought clean water to New York City and improved public health. Nickolls was working in response to his own recuperation from an accident. In all three artworks, Bethesda represents a place of healing. An actual place becomes a spiritual place in the imaginations of those who then once again actualize it in real and specific locations.

In John’s account, the pool of Bethesda was a place where the sick went to be cured. This point is emphasized in a probable later addition to the text that was included in some translations of the New Testament:

For an angel of the Lord went down at certain seasons into the pool, and stirred up the water; whoever stepped in first after the stirring of the water was made well from whatever disease that person had. (John 5:4)

The verse is usually footnoted in modern translations, but the angel stirring up the waters has a strong reception history in art, and includes the works by Hogarth and Stebbins discussed here.

This narrative is about more than a man being restored to health, however. As is highlighted by Hogarth’s depiction of the mother of a sick baby being pushed aside by the servants of a wealthy woman, access to the pool in Jerusalem may have been limited by various forms of social capital. John hints at such restrictions in the words of the sick man who tells Jesus that he has no one to help him into the pool when the waters are stirred up (v.7).

Stebbins’s Angel watches over Bethesda Terrace in Central Park, a public space that is open to all. But for much of its history, Central Park was a place only for the white elite, and part of the space on which it was built in the nineteenth century was Seneca Village, which was home to black and Irish communities. Their homes and communities were destroyed by the park. This was a place where, as at the pool in Jerusalem, some were excluded.

In this narrative, Jesus challenges the status quo. He heals the man whom society has marginalized, and he does so on the Sabbath, which leads to his own persecution (v.16). Hogarth’s depiction of injustice at Bethesda, and the histories of Central Park in which Stebbins’s Angel is situated, resonate with this aspect of John’s narrative. They can remind the viewer that Jesus was an activist, and can encourage us to emulate Jesus’s example of challenging injustice. How can we, like Jesus, heal sicknesses in our societies, whether medical, spiritual, or political?

Nickolls’s Bethesda series is more introspective and can therefore speak to John’s narrative in a different way. The drawings were produced while Nickolls was recovering from a car accident. They are a response to the artist’s physical recuperation, but are also a cathartic meditation upon—and were part of—Nickolls’s process of recovery as a whole. A violent accident leaves more than physical scars.

When Jesus and the man that he healed at Bethesda later meet in the Jerusalem Temple, Jesus says to him, ‘See, you have been made well! Do not sin any more, so that nothing worse happens to you’ (v.14). The implication is that the man was morally as well as physically unwell. The association between moral and physical health here and in other episodes in Jesus’s ministry may no longer be accepted, and we can read that identification as allegory. Nevertheless, this aspect of the narrative highlights that there are different kinds of illness, and for this reason Jesus’s example can stand for different kinds of healing.

As expressions of his psychological recovery from his accident, the works in Nickolls’s Bethesda series are about more than physical healing. Jesus’s parting words to his patient also assert that the man must play a role in ensuring his own continued health. We might see a parallel too in Nickolls’s support of his own recuperation through his art. He imagines his own restorative world in his Dreamtime landscapes.

In these three artworks, Bethesda variously stands for a place of medical treatment, for clean water and public space, and for recovery from trauma through the practice of art. They therefore speak to different types of healing. The works and their contexts can also challenge viewers to emulate Jesus’s work at Bethesda by creating their own places of healing.

Commentaries by Naomi Billingsley