Matthew 14:6–11; Mark 6:21–28

Salome’s Dance

Unknown English artist

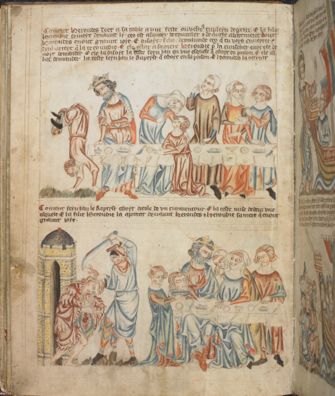

Salome's dance; the death of St John the Baptist, from the 'Holkham Bible Picture Book', c.1327–35, Illumination on parchment, 285 x 210 mm, The British Library, London; Additional 47682 fol. 21v, © The British Library Board (Add MS 47682, fol. 21v)

Balanced Body, Unbalanced Soul?

Commentary by Michaela Zöschg

This is one of over 230 illuminations depicting episodes from the Old and New Testaments. The illuminations are assembled in a manuscript known as the Holkham Bible Picture Book, and were probably made for a wealthy patron in fourteenth-century England.

The illumination shows Herod’s birthday celebrations at a richly laden banquet table, with the king and his wife Herodias feasting among a group of courtiers in fashionable fourteenth-century dress.

To the left of the table, Herodias’s young daughter performs her dance for Herod. As in the Scriptures, she remains nameless in the short text accompanying the image. She is depicted balancing on her hands, arching her back, and throwing her feet backwards into mid-air as if to perform a somersault. Such acrobatic entertainment would have been familiar to a medieval audience from the performances of jugglers, acrobats, and dancers at real-life festivities.

Dance had an ambivalent status in medieval Europe. While the Christian church conceived of the harmonious movements of angels and righteous souls in Paradise as an expression of mystical joy in the presence of God, dance on earth—especially when demonstrating exaggeration of movement—was often interpreted as a sign of a socially and morally reprehensible character, as a sign of an unstable soul, and even as a sign of madness. Medieval artists therefore often depicted Herodias’s daughter performing the elaborate contortions of a juggler to convey the ambiguity of her dance and character—both thought to have contributed to John the Baptist’s death.

In the Holkham Bible, the girl’s ambiguous role is further enhanced by juxtaposing the moment of her dance with the moment she receives Herodias’s instruction to ask for John the Baptist’s head as her reward. Using the narrative device of simultaneity, the painter shows the girl kneeling in front of the banquet table, where she obediently receives her mother’s orders, and is thus transformed into a murderous weapon.

References

Baert, Barbara. 2013–14. ‘“The Daughter Came in and Danced’: Revisiting Salome’s Dance in Medieval and Early Modern Iconology’, Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen s.n.: 152–92

Klapisch-Zuber, Christiane and Susan Emanuel. 2017. ‘Salome’s Dance’, Clio: Women, Gender, History, 46: 186–97

Hans Horions

Salome Dancing for Herod, c.1634–72, Oil on canvas, 176 x 133 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; SK-A-804, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Piercing Gazes

Commentary by Michaela Zöschg

The Roman–Jewish Historian Flavius Josephus was the first to give a name to Herodias’s daughter. In his Antiquities of the Jews, written in the year 93 or 94 CE, he introduces the girl as Salome—a name which over the following centuries would be attached to many different, often contradictory, but always imagined personae.

Hans Horions, a rather elusive seventeenth-century artist who worked in the Dutch city of Utrecht, painted his Salome in an austere Calvinist climate. The Dutch Reformed Church at the time fiercely opposed dancing. For instance, in a ‘Sermon against Dancing’ (Predicatie tegen ‘t dansen), published in 1643, the story of Salome and Herod is used to illustrate the fatal effects of dance. Its author, Joannes Naeranus, argues that it was the young woman’s seductive dance that led the king to commit an act of evil against his own free will.

In Horions’s painting, Herod and his birthday party appear to be spellbound by Salome’s performance. They gaze at her transfixed, ready to give her whatever she will ask for. Herodias, bathed in the same bright cool light as her daughter, is visually cast as Salome’s counterpart at the right of the painting. Her eyes seem to follow the dancer’s every move, like those of a puppet master directing her marionette’s strings, the large gleaming platter on the buffet behind her heralding the consequence of her actions: a killing.

The dancer herself, depicted in line with earlier Renaissance tradition as an idealized beauty and artistic muse, advances her sandal-clad foot, her high slit dress exposing a bare leg. This Salome is engaged in an active act of looking of her own. She gazes out of the painting, directly addressing the spectator, turning him or her into a witness, or perhaps even an accomplice.

References

Brooks, Lynn Matluck. 1988. ‘Court, Church, and Province: Dancing in the Netherlands, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries’, Dance Research Journal, 20: 19–27

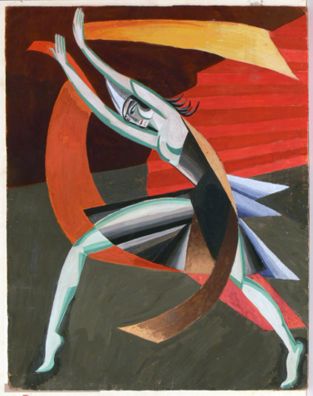

Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Exster

Costume Design for Oscar Wilde’s Salome, 1917, Pencil, tempera, gouache, whitening, silver, bronze and varnish on cardboard, 66.5 x 52.6 cm, A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum, Moscow; КП 62579, © A. A. Bakhrushin State Central Theatre Museum, Moscow

Kaleidoscopic Whirlwind

Commentary by Michaela Zöschg

As the nineteenth century turned to the twentieth, artistic interest in the figure of Salome reached new heights. An unusually large number of painters, sculptors, and writers turned towards the biblical dancer with renewed interest, and transformed the girl whom the Bible described as a mere instrument of Herodias’s wrath into an active agent of female desire, casting her as the prototype of the ‘femme fatale’.

Oscar Wilde’s play Salome, first performed in Paris in 1896, was one of the key works that established Salome’s fame as cultural icon of fin-de-siècle Europe. In Wilde’s drama, Herodias and her vengeance retreat to the background of the story, while Salome’s twisted desire for the prophet Jokanaan (John the Baptist) comes to the fore. Aware of her own sensuality and sexual power, she is driven by her obsession to kiss the prophet, which in the end, will cause not only his, but also her own demise.

Wilde’s drama was particularly enthusiastically received in Russia, where his femme fatale underwent yet another transformation in the context of the emerging Soviet state. Here, she was re-interpreted as an androgynous and Amazon-like character, and transformed into an emblem not only for a new artistic avant-garde indebted to Futurism, Cubism, and Constructivism, but also for a new, energetic, and determined woman born out of the Revolution.

Aleksandra Ekster’s designs for Aleksandr Tairov’s 1917 production of Wilde’s Salome at the Kamerny Theatre in Moscow are perhaps the most radical embodiments of these ideas. In her costume design for Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils, shown here, Ekster strips the dancer of all connotations of sensuality and eroticism. Instead, Salome’s passions and destructive desires are transformed into an energetic kaleidoscope of movement and colour, her body merging with the stage behind.

References

Misler, Nicoletta. 2011. ‘Seven Steps, Seven Veils: Salomé in Russia’, Experiment, 17: 155–84

Unknown English artist :

Salome's dance; the death of St John the Baptist, from the 'Holkham Bible Picture Book', c.1327–35 , Illumination on parchment

Hans Horions :

Salome Dancing for Herod, c.1634–72 , Oil on canvas

Aleksandra Aleksandrovna Exster :

Costume Design for Oscar Wilde’s Salome, 1917 , Pencil, tempera, gouache, whitening, silver, bronze and varnish on cardboard

Salome Re-imagined, Re-invented, Re-Constructed

Comparative commentary by Michaela Zöschg

In the Scriptures, the dance of Herodias’s daughter is a comparatively minor detail in a much larger story about desire and hatred. The main characters are John the Baptist on the side of righteousness, and Herodias, whom he had outed as adulteress and lawbreaker, on the side of evil. The nameless dancing girl, who would later gain fame as Salome, and to a lesser degree perhaps Herod as well, occupy the ambiguous empty space in between these two extremes.

The figure of the dancing girl in the Bible story provided a blank sheet onto which artists at different times, and in different places, projected their ideas about women. Over the centuries, the dancer therefore assumed many guises, connected both to fears and to desires surrounding male notions of womanhood. Acrobatic dancer, seductive nymph, self-assertive muse, violent revenger, and dangerous femme fatale are only a few among them. The artworks chosen for this exhibition show how Salome was imagined in Europe at three specific points in time, and explore three of her many bodies and faces.

The fourteenth-century illuminator of the Holkham Bible pairs Salome’s dance with Herodias’s instruction to ask for John the Baptist’s head on a platter, and emphasizes an interpretation of the young girl as a child without much agency of her own. Here, she is the obedient and passive tool of Herodias’s desire for vengeance. Salome’s contorted malleable limbs as she dances manifest her equally malleable soul, which leads in turn to the ambiguity of her actions.

Following the Renaissance tradition of depicting Salome as the epitome of idealized femininity and the essence of the artistic muse, Hans Horions’s seventeenth-century Salome appears, by contrast, as a self-assertive individual who performs her dance with confidence. Ignoring the male gazes piercing her body from all sides, she directly addresses the audience outside the picture frame, thereby inviting them to become complicit in her doubtful actions. She has already begun to manifest the alluring powers of the femme fatale into whom she would be transformed in the nineteenth century. Horions’s Salome is shown as her mother Herodias’s equal, taking an active share in the sin of the prophet’s murder.

Constructivist artist and stage designer Aleksandra Ekster could look back on a decades-long tradition of Salome images that drew on her sensuality and dark power as femme fatale. In post-revolutionary Russia, she developed an innovative stage setting and costume designs which presents Oscar Wilde’s Salome, a fin-de-siècle icon, as dissolved in colour and movement. In a sense, the fractured figure in Ekster’s sketch provides the perfect expression for a character as multifaceted and elusive as Herodias’s dancing daughter.

All three Salomes—medieval, early modern, and modern—tell us different yet connected stories, not only about the ambiguity of what different societies attach to the concept of ‘woman’, but also to the concept of ‘dance’. On the one hand dance is perceived as an expression of celebration and joy, but it is also associated with excess and danger. As such, the dancing daughter is the perfect projection screen for our fears and desires, and the perfect reminder of the complexity of what it means to be human.

References

Neginsky, Rosina. 2013. Salome: The Image of a Woman Who Never Was; Salome: Nymph, Seducer, Destroyer (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing)

Commentaries by Michaela Zöschg