Ephesians 2

Alive Together With Christ

Works of art by Beryl Dean, Eleanor Antin, The Stanhope Educational Institute Embroiderers and Unknown Spanish artist [Asturias]

Unknown Spanish artist [Asturias]

Processional Cross, c.1150–75, Silver, partially gilt on wood core, carved gems, jewels, 59.1 x 48.3 x 8.7 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917, 17.190.1406, www.metmuseum.org

Raised Up With Christ

Commentary by Ayla Lepine

This twelfth-century cross was originally used to lead processions at the beginning and end of the Eucharist. Its glittering metalwork and embedded jewels convey the idea that death will be transformed into a more glorious life. It also demonstrates the wealth and power of the medieval kingdom of Asturias in northern Spain where it was made.

Its True Cross relic still remains, magnified and protected by a translucent slice of rock crystal positioned above Jesus’s head, operating both as halo and as transfigured crown of thorns. The three-dimensionality of the body of Jesus, the head and shoulders of which strain outwards, contrasts with the relatively flat relief of the figures of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St John the beloved disciple on the cross’s arms.

A Latin inscription on the reverse reads: ‘In honour of the Holy Saviour: Sanccia [Sancha] Guidisalvi had me made’. Medievalists have pointed out that the feminine ending of Sanccia indicates that either the donor or the goldsmith was a woman.

The design of the cross combines antique iconography with medieval Christian elements. The gems surrounding the image of the crucifixion include an intaglio from antiquity representing Victory. This Graeco-Roman goddess has been repurposed within the splendour of the cross. Now she helps to glorify the hope of resurrection that flows from the horror of crucifixion, bearing witness to it as the Roman centurion does when he utters ‘Truly this was the Son of God’ (Mattthew 27:54).

Ephesians 2 speaks of two inclusions achieved in the Body of Christ. Those who were once ‘dead through trespasses and sins’ (v.1)—and who lived in ‘the passions of the flesh’ (v.3)—are now saved ‘by the gift of God’ (v.8). And those who were ‘strangers’ to Israel’s ‘covenants of promise’ (v.12) are now ‘members of the household of God’ (v.19).

As ‘one new humanity’, Christ’s Body defines a sacred community which has no ‘outside’ and no outsiders. All are one in a new promise that does not deny or override diversity but incorporates it into a transformatively inclusive whole.

Beryl Dean with the Stanhope Educational Institute Embroiderers

The Jubilee Cope, 1976–77, White flannel with gold, silver, copper, and silk, St Paul's Cathedral, London; © Beryl Dean Education Trust; Photo: © St. Pauls Cathedral

A Whole Structure Joined Together

Commentary by Ayla Lepine

For Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee in 1977, the British textile artist Beryl Dean designed a cope, mitre, and stole for St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Her choice of imagery was inspired by the Diocese of London’s parish churches. Thirty-six people in the Ecclesiastical Embroidery class at the Stanhope Adult Education Institute worked on sections of the embroidery simultaneously. Dean devised the design with this simultaneity in mind. Her aim was that it would be both efficient and collaborative.

Medieval and modern, neoclassical and Gothic, every tower and spire was stitched and labelled with its dedication and location onto the body of the cope, interweaving text and image in a cluster of portraits of these diverse yet unified places of worship. Its aesthetic not only reflected the features of each building, but made material reference to the Jubilee itself, as (along with fawn) its dominant colours were white and silver, with details embroidered in gold.

When complete, the cope transformed the body of the wearer, the Bishop of London, into a microcosmic representation of the Body of Christ in the city—and, by extension, across the nation, and throughout the Anglican Communion. Flesh, through grace, was clothed with the Body of Christ.

The cope, mitre, and stole together ‘house’ and enfold the bishop, connecting her anew to the people and places in which she serves and leads, as a symbol and source of unity. It is a unity both physical and temporal. Though created to mark a particular event of historic significance, these vestments make connections through time as they continue to be used. Every time the cope is worn for a key festival in the Church’s life, it evokes the Body of Christ which is yesterday, today, and forever. It forms a historical layer around the wearer and throughout the congregation, connecting past, present, and eschatological future.

In geographical terms, too, it is a focal point. Churches that, scattered throughout the city, ‘were far off’, have in this one garment been ‘brought near’ (Ephesians 2:13) in this image of a city in which all spaces are consecrated to God. It celebrates the reach and the coverage of a parish system which binds city and nation into ‘one body’. As each strand of the cope is woven together physically, so each location is shown to be bound together spiritually as ‘a dwelling place of God’ (v.22).

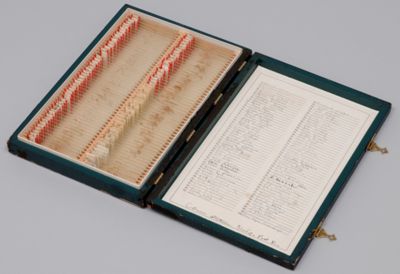

Eleanor Antin

Blood of a Poet Box , 1965–68, Wood box containing one hundred glass slides of blood specimens, 29.2 x 19.7 x 3.8 cm, Tate; T14882, © Eleanor Antin; Photo: © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Citizens with the Saints

Commentary by Ayla Lepine

Eleanor Antin’s mid-twentieth-century artwork Blood of a Poet Box is a found object repurposed as a quasi-reliquary, blending the cultural vocabulary of conceptual art, the archive, the medical specimen, and the Church.

The green box contains one hundred glass slides. Each slide contains a blood sample that Antin drew out with a sewing needle from a poet in the New York City scene of which she was a part. It is the blood of her friends.

She defined ‘poet’ loosely, and she included artists, performers, and dancers among those who bled for her. She gathered the blood at art events including readings and performances in which the artists were centre stage.

It has elements of a specimen collection, taxonomized and labelled. Yet the medical quality of the work sits uncannily alongside the home-made improvisational aesthetic, which is particularly marked in the list of signatures from the poets, alongside her own signature as the work’s creator. The distinctive differences between the poets are rendered as variations in handwriting and not just in blood type.

This box is thus more than a specimen collection. It can also be compared to a portable reliquary, in which the poets of the city are enshrined. Unlike traditional relics, though, this material was gathered when its donors were alive. Rather than signalling martyrdom, their blood indicates ongoing vitality, and the sites where art is produced: deep within the marrow, the heart, the mind—the places where blood courses and flows.

Diane Wakoski, one of the poets included in Blood of a Poet Box, wrote of Antin’s collecting of relics in a 1965 poem responding to the work.

Collecting is more than just an attraction to objects. Antin explored her own identity in and through her relationships with the artists she knew, in the words of Wakoski’s poem: ‘weaving’ and ‘attaching’ them. By creating an archive as a ‘group portrait’, her box filled with blood samples was also a ‘self portrait’.

And in her collection of these samples, she rendered her artistic circle saint-like. ‘Brought near’ (Ephesians 2:13) by blood as well as in spirit, proclaiming their truth boldly, being ‘made for good works’ (v.10), they are displayed as ‘alive together’ (v.5).

References

Wakoski, Diane. 1973 [1965]. ‘A Long Poem for Eleanor Who Collects the Blood of Poets’, in Dancing on the Grave of a Son of a Bitch (Los Angeles Black Sparrow Press), pp. 119–20, available https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/in-focus/blood-poet-box/a-long-poem [accessed 20 August 2019]

Unknown Spanish artist [Asturias] :

Processional Cross, c.1150–75 , Silver, partially gilt on wood core, carved gems, jewels

Beryl Dean with the Stanhope Educational Institute Embroiderers :

The Jubilee Cope, 1976–77 , White flannel with gold, silver, copper, and silk

Eleanor Antin :

Blood of a Poet Box , 1965–68 , Wood box containing one hundred glass slides of blood specimens

Built Together Spiritually

Comparative commentary by Ayla Lepine

The first cluster of verses in Ephesians 2 (vv.1–10) consider the promised and urgently needed transformation of life from a path of transgression towards a path led by Christ.

The transition is no less than a resurrection of the self in anticipation of the promised eschatological resurrection offered through Christ. From death to life, every aspect of a person is renewed through Christ. Through Christ we are called to build each other up in love as the Body of Christ.

Verses 11–22 take this imagery and develop it into a further crescendo of encouragement: the one and the many are united in Christ into a body reconciled through the cross, and into a temple of which Christ is the cornerstone. This emphasis on unity and inclusion is a uniquely strong one in Ephesians.

All of the artworks in this exhibition are in some way collaborative, and feature women artists lending their skills to visions of unity. The twelfth-century Spanish processional cross in this exhibition was probably commissioned by a woman. The two modern artworks—a cope for celebratory moments in the Church year at St Paul’s Cathedral, and a conceptual work of art that offers a minimalist Modernist habitat for drops of artists’ blood—were made by women. Cope and cross were made for liturgical use, where the unity of the Christian body is visibly performed. Meanwhile Eleanor Antin’s box is theologically rich in its echoes of the Church’s history of devotion to relics.

Ephesians 2’s argument about the many who are united in Christ is reflected in the mixed media of these artworks, too: the gems, the threads, and the blood all originate in radically different places, times, and bodies and are drawn together into a whole. Each artwork, in its distinctive way, accomplishes an act of inclusion.

Ephesians 2’s prioritisation of transformation and unity, and its rich imagery of bodies and sacred spaces, lends itself well to connections with these diverse works of art. The cross incorporates classical intaglios alongside medieval Christian imagery and positions a reliquary directly above Christ’s head. The cope represents all the churches in the Diocese of London, brought together into ‘one body’, worn by the bishop as a symbol of unity, stitched by women who worked separately on each church ‘portrait’ with its own inscription, all to Beryl Dean’s design. Blood of a Poet Box is a ‘group portrait’ Antin produced using an old sewing kit’s needles to extract blood samples from her chosen poets. Like the cope—and the cross too—it provides a setting in which diverse fragments can be gathered together—‘congregating’ in the ‘one body’ of a sacred community. In this way, the box does not merely contain the life essence of 100 poets (represented by their blood and a list of names), but fashions a more striking and yet stable ‘dwelling’ for these artists’ bodily substance.

Naming is a further key aspect of the three artworks. The cross is marked by the name of the woman who either made or commissioned it. The cope is marked by the names of the churches, themselves emblems of the Body of Christ surrounding the body of the bishop when the cope is worn. Antin’s box contains meticulously named blood samples. Each name marks a distinct identity, but also a building block in a greater whole.

The purpose of the processional cross (to lead towards the altar and direct the ministers and congregation to the sign of Christ at key points in the liturgy), the cope (to clothe the bishop as epicentre of unity during particular holy days of celebration) and the box (to house the ‘saints’ of a modern artistic community as a united body), connects with the core idea the passage in Ephesians, which overall is focused on encouragement and the priority of unity over tribalism or division.

The resonance between these three items is exciting to pursue; the span of time between the twelfth century and the twentieth, and the span across continents, stretches well beyond a single mode of visual communication. Both the representational and abstract contexts complicate classic categories of sacred and secular within art history. Moreover, as a trio of artworks by or commissioned by women, each emphasizes the collaborative and diversely gendered nature of making, gathering, devotion, and worship.

![Processional Cross by Unknown Spanish artist [Asturias]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0379_Unknown+Spanish+artist_Asturias_Processional+Crosscropped.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Ayla Lepine