Ephesians 4:1–16

The Birth of the Church

Works of art by Andrey Rublyov, Michelangelo Buonarroti and Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

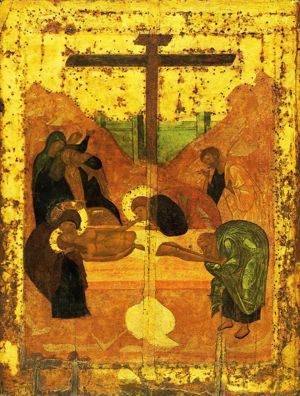

Andrey Rublyov

Deposition, 1425–27, Tempera and gold on panel, 88 x 68 cm, The Trinity Cathedral in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, Sergiev Posad, Russia; Inv. 3053, akg-images / Album

One Body, Many Members

Commentary by Paul Anel

This icon was written in 1425–27 by the Russian monk Andrey Rublyov. The scene is traditionally referred to in the East as the Epitaphios, or Lamentation over the Grave. The body of Jesus, laid flat on the tomb, is surrounded by a group of lamenting disciples, separated in the middle by the axis of the cross: to the right, Joseph of Arimathea, John the Apostle, and Nicodemus are bending over Jesus’s remains—the latter two reverently kissing them; to the left Mary, the mother, is silently holding his head and tenderly pressing her face against his, while in the background three women seem to be crying aloud in despair.

This group of seven disciples stands for the entire Church, organized, as it were, along two foundational axes: the horizontal axis of Jesus’s body, and the vertical axis of the cross. The Church is the ‘Body of Christ’ inasmuch as all its individual members orbit around the body of Jesus, and are assigned a function defined by their respective relationship to Jesus’s body parts. To Nicodemus, the hidden disciple, is assigned the most hidden part of Jesus’s body, the foot; to John, the priest, is assigned the very hand that held the bread and wine at the Last Supper; to the mother, Mary, is assigned the head, which first came out of her womb.

Besides Jesus and Mary, John is the only one whose head is surrounded by a halo, which singles out the ‘trinity’ formed by these three characters. Face to face, Jesus and Mary are represented in a loving, intimate embrace that is the beating heart of this icon. John’s gaze points exactly in that direction, as if enraptured by the mystery of their union. The Epitaphios is not about death, it is about life: the living tree of the Church stems from the ‘bond of peace’ (Ephesians 4:3) between the New Adam and the New Eve.

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Pietà for Vittoria Colonna, c.1538–44, Black chalk on paper, 28.9 cm x 18.9 cm, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston; inv. 1.2.o.16, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA, USA / Bridgeman Images

‘Blessed Are You Who Believed!’

Commentary by Paul Anel

This carefully finished drawing of the Pietà was made by an ageing Michelangelo in 1538 as a gift for Vittoria Colonna. A deeply religious spirit, this widow of an imperial general was the only woman in the artist’s exclusive circle of intimate friends. She was more than a friend to him: she was a spiritual sister on his journey upward, much like Beatrice was to Dante in The Divine Comedy. This background is not irrelevant to the drawing itself, for it is the celebration of a spiritual bond between a man, Jesus, and a woman, his mother.

The Pietà as an artistic subject spotlights the Virgin, usually alone, at the moment when she receives the lifeless body of her son, just taken down from the cross.

Here, the body of Christ is exposed in frontal view, his arms slung over his mother’s thighs and further supported by two angels. Inscribed on the vertical beam of the cross, words rise above Mary as if recording her thoughts. They are a quotation, now cropped, from Canto 29 of Dante’s Divine Comedy: Non vi si pensa quanto sangue costa (‘there they don’t think of how much blood it costs’).

What is immediately striking in this Pietà is the counterpoint between Mary’s body and her son’s: his head is bowed down, hers is raised up; his forearms are hanging, lifeless, hers are prayerfully raised to heaven; his hands are folded in, hers are wide open to give and receive. If Jesus’s body language speaks of his ongoing descent on Holy Saturday, Mary’s hopeful and ecstatic attitude seems borrowed from an Assumption.

This drawing dramatically emphasizes the contrast, and correlation, between Jesus’s death and Mary’s faith. She is represented not just as the sorrowful mother, but as the one the Early Church Fathers called the ‘New Eve’, the ‘helper fit for him’ (Genesis 2:18) who offered to his Passion the response of the ‘one faith’ and the ‘forbearance of love’.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Deposition, c.1600–04, Oil on canvas, 300 x 203 cm, Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City; inv. 40386, Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

Descent / Ascent

Commentary by Paul Anel

In this 1603 altarpiece executed for a chapel of the Oratory of St Philip Neri, Caravaggio delivers a poignant rendition of Christ’s deposition and entombment. The compact group of disciples is arranged in three rows. In the front row, the men—John and Nicodemus—are busy supporting the dead body of Jesus, slowly ushering it into the tomb. In the second row, two women offer a more spiritual participation in the event: Mary, the mother of Jesus, is bowed in prayer, her right hand outstretched over her son’s face in a gesture of acceptance and blessing, while Mary Magdalene sheds silent tears over the one who delivered her from seven demons (Luke 8:2). In the back row, Mary, wife of Cleopas, raises her arms emphatically, crying to heaven.

That Christ ‘descended into the lower [regions] of the earth’, as St Paul puts it (Ephesians 4:9), is quite literally what Caravaggio represented here. As it hangs above the altar in the church of Santa Maria in Valicella in Rome, the viewer’s gaze is exactly aligned with the surface of the earth, objectified by the thick, flat tombstone, whose angle points in our direction. Jesus’s body, whose movement is highlighted by the lowered arm and the white linen flowing like water from his side, is being hauled down by the disciples into the impenetrable darkness underneath the stone.

Alongside its narrative content, Caravaggio’s painting sheds light on the ecclesiology of St Paul. The group of disciples, with its male/female and active/contemplative components, is archetypal of the Church in its entirety. The body of Christ, bathed in light, lies at the bottom of the composition, while the group of disciples is, as it were, ‘built’ on that foundation.

Furthermore, the descending movement of the body is balanced by the ascending movement of the disciples, from the front to the second row, and from there to the last, where Mary stands, her hands outstretched towards the light.

Andrey Rublyov :

Deposition, 1425–27 , Tempera and gold on panel

Michelangelo Buonarroti :

Pietà for Vittoria Colonna, c.1538–44 , Black chalk on paper

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio :

Deposition, c.1600–04 , Oil on canvas

The Miracle of Unity

Comparative commentary by Paul Anel

All three artworks in this exhibition highlight the words of Ephesians: ‘he who descended is he who also ascended far above all the heavens’ (4:10). In Caravaggio’s Deposition, the body of Christ is being hauled down, while the pyramidal body formed by the disciples seems to rise into the light. In Michelangelo’s drawing, it is the faith of Mary that is singled out as humanity’s ‘assumption’ into heaven. In Andrey Rublyov’s icon, the birth of the Church as Body of Christ is a direct consequence of Jesus’s descent.

Descent and ascent are contemplated, therefore, not just as a chronological sequence but as contemporaneous and correlated events that respectively affect the body of Jesus in its physical (descent) and ecclesiological (ascent) forms. The ‘ascent’ (birth) of Christ’s mystical body is caused by the ‘descent’ (death) of his physical body.

The three images yield further meaning when juxtaposed with St Paul’s words about unity and multiplicity in Christ’s mystical body. Multiplicity is given by the members, ‘joined and knit together by every joint with which [Christ’s body] is supplied’ (v.16). In Caravaggio’s painting, and even more so in Rublyov’s icon, there is a clear correlation between the physical body of Jesus and the multiplicity of functions—both contemplative and active—within the Church.

If the physical body of Jesus appears to be the principle of multiplicity within the Church, what, then, is her principle of unity? To be constituted as ‘Body of Christ’, the group of the disciples needs a formal principle of unity, in the same way that the soul binds the multiplicity of members into one human body.

This question is all the more dramatic given that the group of the disciples looks rather divided (compare, for instance, John 20:1 and 20:19). The Church appears to be fragmented into a wide array of subjective reactions: sorrow, fear, despair...

Michelangelo’s Pietà drawing highlights the relationship between Mary and Jesus. Mary’s role in the Passion has traditionally been seen as unique, qualitatively different from that of the other disciples. As St John Paul II puts it, after the death of Jesus, ‘Mary alone remains to keep alive the flame of faith’ (John Paul II 1997). Michelangelo’s drawing of the Pietà is a contemplation of this mystery: the faith of Mary on Holy Saturday. Her arms are raised towards heaven in the traditional orans (‘praying’) attitude while her face expresses gratitude more than sorrow.

We are faced with a seemingly impossible and yet undeniable fact: since Christ is the object of the Christian faith, his death should logically entail the death of faith. This is true for all the disciples, with the exception of Mary, whose faith miraculously perdures throughout the hiatus of Holy Saturday.

The Pietà, according to Tradition, singles out Mary as the principle of unity of the Church. It is, as Ephesians puts it, the ‘one faith’ that makes the Church one, and the reason the faith is one (without suffering a subjective fragmentation after the death of Jesus) is that it was historically at one point in time (on Holy Saturday)—and therefore is ontologically at every point in time—the faith of one (person), namely, the faith of Mary.

In Rublyov’s icon, the disciples are entrusted with the care of Jesus’s body, while his head—locus of his spirit—rests on his mother’s womb. The icon thus traces a visual hyphen between Jesus’s body laid in the virgin tomb and his conception in the mother’s virgin womb. Mary’s motherhood received, from the crucifixion onward, a new meaning and extension: as she was the mother of his physical body, she now becomes, by grace, the mother of his mystical body.

It is not a coincidence that John, in Caravaggio’s painting, stands between Jesus and Mary. Jesus spoke to him personally when he said: ‘Behold your mother’ (John 19:27). He stands in the space between ‘New Adam’ and ‘New Eve’ as the fruit of their love. Mary’s right arm binds the group together, as if her faith, hope, and love was mysteriously communicated to John, and, through him, to the Lord.

Tradition tells us that John would later spend many years in the intimacy of the mother of Jesus in Ephesus. It makes sense, then, that it was by way of her spiritual motherhood that he would ‘grow up in every way into [Jesus]’ (v.15). The same holds true for each one of us.

References

Pope John Paul II. (1997). ‘General Audience, 21 May 1997’, available at http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/audiences/1997/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_21051997.html [accessed 01 April 2020]

Commentaries by Paul Anel