Ephesians 5:3–20

Children of the Light

Caspar David Friedrich

Caroline on the Stairs (Woman Ascending to the Light), c.1825, Oil on canvas, 73.5 x 51.5 cm, Pommersches Landesmuseum, Germany; Pommersches Landesmuseum, Germany / Bridgeman Images

What Kind of Light is This?

Commentary by Johann Hinrich Claussen

Caspar David Friedrich created this small painting in 1825. It is called Woman Climbing up to the Light and shows his wife Caroline going up the steep stairs in their house—seemingly an everyday scene. But there is a provocation in this motif. These stairs are a deeply undistinguished part of the house: narrow, cold, dark, ugly—not worthy of being painted. And yet there is a sense of magic, of mystical enchantment in this painting. A secret force, it seems, elevates the woman from the dark and depressing depths to a higher and brighter level. The light is clear and warm—but apparently without a source. There is no lamp, torch, window, or open door to be seen. It is a light from nowhere. Or is it an inner light that only the painter—or the woman—can ‘see’? She does not look up to the light, but her bearing is unusually upright and easy. There can be just one explanation: she is ‘in’ the light.

The first Christians lived in a paradox. They had received God’s redeeming grace and yet continued to lead a modest or even miserable life. Ephesians 5 stresses the newness of Christian existence: ‘You were darkness, but now you are light in the Lord’ (v.8). What kind of a light is this? It must be an inner force that transforms an existence that outwardly may not change all that much. In this sense, Friedrich’s painting can be seen as a modern commentary on this ‘inner light’. It gives an idea of what it means to live in the light, to be light in the Lord, overcoming the barriers between dark and light, down and up, depression and hope, death and life, the immanent and the transcendent.

References

Hofmann, Werner. 2000. Caspar David Friedrich (New York: Thames and Hudson)

Georges de La Tour

The Newborn Child, c.1645, Oil on canvas, 76.7 x 92.5 cm, Musee des Beaux-Arts, Rennes, France; Photo: Louis Deschamps © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

A Choreography of Light

Commentary by Johann Hinrich Claussen

A newborn child can only flourish in a loving relationship. And it gives a whole new life to those that care for it. Therefore, Georges de La Tour shows the newborn Jesus Christ in intimate connection with his mother, and accompanied by a second woman, perhaps a midwife. Everything that matters is here.

Everything else is faded out in darkness: there is no Joseph, no stable, animals, shepherds, or kings. Only these three persons are to be seen in their intense connection. This intimacy is stressed by a special choreography of light. There is just one source of light, that makes the three visible, but itself can barely be seen. The second woman holds it with one hand and protects (and covers) it with the other one.

So one may ask, who actually illuminates whom? Does the candle shed light on the child or is it the child who gives light to the women? This is more than an aesthetic trick. Rather, a symbolic truth is revealed here: the light of faith is fulfilled in a reciprocal illumination. It is as though the child illuminates the two women, whose affection gives him light in return. Here is a spiritual occurrence which—though a quiet moment of peace and love, outwardly silent—is yet at the same time inwardly charged with the most powerful of dynamics.

This mystical moment carries with it also an ethical motif: it underlines the importance of affection, attention, concentration, purity, and silence. In the light of this painting, Ephesians 5 can be read differently: not as a rigorous catalogue of ethical demands, but as a sermon on the fundamental and complex Christian symbol of light, and on the consequences it may have for one’s own life.

References

MacGregor, Neil, with Erika Langmuir. 2000. Seeing Salvation: Images of Christ in Art (London: BBC)

Elisabeth Coester

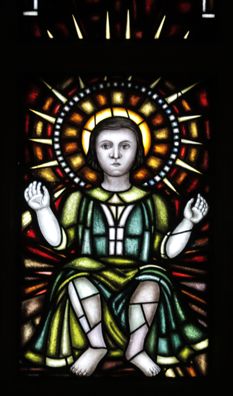

Young Christ, 1939, Stained glass, Whole window approx. 22 x 8 m, St Nikolai, Hamburg; Photo: © Hinrich Franck, courtesy of St Nikolai, Hamburg

In Evil Days

Commentary by Johann Hinrich Claussen

This is a small segment of a huge stained-glass window (22 x 8 metres) created in 1939 by Elisabeth Coester for the church of St Nikolai in Hamburg. It is one of only a few works by her that have survived.

Coester became famous for the gigantic stained-glass walls (800 square meters!) she formed in 1928 for the avant-garde ‘Steel Church’ in Essen and a similar work for St Nikolai in Dortmund a year later. These two masterpieces of modern church architecture were destroyed or severely damaged during the Second World War.

Today Coester is almost forgotten, for several reasons: she was a modern artist who worked mainly for the Protestant church; she died early at just 41 (in 1941); her work consisted mostly of stained glass and was doomed in the war; and—last but not least—she was a woman.

In her window for St Nikolai, she combines traditional motifs with a modern aesthetic and a courageous message. Christ is not, as was common in German churches during the Nazi regime, portrayed as a heroic man or a powerful ruler, but a defenceless child. Centuries of Western images—from later medieval through to Renaissance times and beyond—have depicted this child as a newborn, naked infant sitting on his mother's lap. But here, he is preciously dressed, sitting upright, presenting himself as a paradoxical Lord of Peace. He—and not an emperor in Rome, or anywhere else—rules the world, and not with armies, but with his light.

In the large glass tableau which is its context, this high-up segment is one of the brightest, thus illustrating the words from Ephesians 5: ‘Christ will shine on you’ (v.14; own translation). It reveals the religious core of the Christian talk of ‘children of light’. It is more than a mere catalogue of virtues and rules, but the appearance of a new image of man—in Christ.

This image of Christ does indeed originate in ‘evil days’ (v.16), created for one of the few liberal churches which in contrast to large parts of German Protestantism kept a distance from the Nazi dictatorship, proclaiming an anti-imperial faith.

References

Senn, Gerhard. 2005. Künstler zwischen den Zeiten, Elisabeth Coester (Eitorf: Wissenschaftsverlag für Glasmalerei)

Caspar David Friedrich :

Caroline on the Stairs (Woman Ascending to the Light), c.1825 , Oil on canvas

Georges de La Tour :

The Newborn Child, c.1645 , Oil on canvas

Elisabeth Coester :

Young Christ, 1939 , Stained glass

Living in the Light

Comparative commentary by Johann Hinrich Claussen

It is not easy to picture the addressees of the letter to the Ephesians. Who were they and what were the characteristics of their community? The letter (or sermon) paints an overwhelming picture. This group of early Christians is nothing less than an eschatological ‘household of God’ (Ephesians 2:19); ‘a holy temple of the Lord’ (Ephesians 2:21) right here on earth—whether in the ancient Greek city of Ephesus or some other comparable place in the Graeco-Roman world. Their mundane reality, though, probably looked more humble—more like an African-American storefront church than an established mainline one. The Christians in Ephesus were a tiny minority that called its new members from the fringes of society: outcasts and pariahs.

The letter to the Ephesians tries to reconcile this striking discrepancy with the help of a central symbol of early Christianity: the light. It marks the new existence Christians enter when they start to believe in the risen Jesus Christ. They leave the night of death, despair, and sin; they come into the day of life, hope, and righteousness. Resurrection for them is thus not a remote incident in the history of salvation—or just a miracle that only happened to Jesus of Nazareth. On the contrary, it has become the inner nature of their existence. As believers, they themselves have become ‘light in the Lord’ (Ephesians 5:8). In this they follow their saviour who called himself ‘the light of the world’ (John 12:46). This light shines into the world, but the world cannot comprehend it (see John 1:5). So, the first Christians were living in two realities—the pagan world of the Roman Empire where they were strangers and the inner world of the church to which they belonged as citizens. The essential thing was their inner transformation. This became manifest for them particularly in moments of prophetic ecstasy, glossolalia, rapture, and other forms of pious enthusiasm.

But are there not also other ways to live in the light of faith: more quiet and inward; less dramatic? That is what makes George de la Tour’s image of the newborn child and Caspar David Friedrich’s painting of his wife as she is climbing up the stairs of their house so appealing: faith as an integral part of one’s inner and one’s everyday life—an essential characteristic of personality, and a dynamic that shapes the deepest interpersonal bonds.

It is noticeable that the letter to the Ephesians doesn’t lose itself in the contemplation of spectacular spiritual illuminations but stresses the ethical implications of ‘the light’. Christian enthusiasm has nothing to do with intoxication or shameful behaviour but shines in a way that is good. This goodness can be seen in the acts Christians do (5:9). The beauty can be heard in the songs Christians sing (5:19–20). So being ‘light in the Lord’ is at the same time spiritual, ethical, and aesthetic. Receiving this grace has serious consequences. The symbol of salvation thus becomes a moral maxim: ‘Walk as children of light!’ (5:8).

What follows may seem like a catalogue of laws and prohibitions but it is in service of a symbolic orientation: if you want to live as a Christian then ask yourself whether your thoughts, feelings, words, and actions are transparent and can stand the light of day. So, the Christian test of conscience is a specific form of enlightenment: expose the works of darkness; lead a visible life that does not have to be afraid of being shamed (5:11–14). In the context of the Ephesians congregation that meant to lead a life of sexual responsibility or conjugal faithfulness, and not to take part in any form of idolatry and pagan cult (e.g. 5:3–5, 17–18).

Becoming a Christian thus marks the start of a new life—as a child of light. In de la Tour’s painting, the two grown women become such ‘children of light’ as they are inspired by the purity of a newborn child, standing in his light.

Anyone who tries to live like this follows Jesus Christ, who as ‘light of the world’ came among us as a child. This following, this faith, is the source of a shining, transparent, and honourable mode of life.

And it has consequences that go far beyond the personal arena. If this ‘child of light’, as depicted in Elisabeth Coester’s stained-glass window, stands in opposition to the tyrants of this world, then Christians who follow him have the same duty to resist oppression, injustice, and violence.

References

Weizsäcker, Carl. 1894. The Apostolic Age of the Christian Church, 2 vols, trans. by James Millar (London: Williams and Norgate)

Commentaries by Johann Hinrich Claussen