John 1:1–13

The Word

Unknown French artist (Tours)

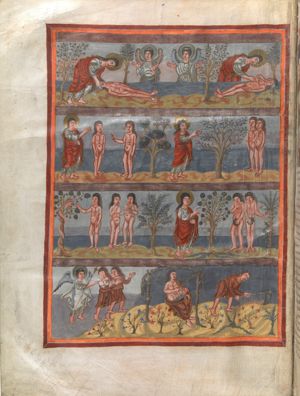

The Genesis Cycle, from the Moutier-Grandval Bible , c.830–40, Illuminated Manuscript, The British Library, London; Add MS 10546, fol. 5v, © The British Library Board (Add 10546, f.5v)

In the Beginning was the Word

Commentary by Jacopo Gnisci

The opening of the Gospel of John tells us that Christ is the ‘Word’ (logos) of God, and is God himself, and that he existed before the world was formed (1:1–2).

This Gospel deeply influenced the development of the Church’s Christology and is rich in biblical citations. For example, its first words echo the first verse of the first book of the Bible as a whole: ‘In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth’ (Genesis 1:1).

This connection reinforces the point that Christ has always existed in the Father, just as the Father exists in Christ. This interpretation was an obvious one to Early Church Fathers such as Jerome (d.420 CE—see his Hebrew Questions on Genesis; Hayward 1995: 30), who translated the Bible into Latin.

Early Christian and medieval artists drew on such interpretations of John’s Gospel for portraying God in the Old Testament. In treatments of Genesis, for example, the Creator is represented as Christ to underscore the fact that He existed prior to his Incarnation (Kessler 1971). This can be seen in a sequence of miniatures that served as a frontispiece to the book of Genesis in the Moutier-Grandval Bible: a large ninth-century pandect—that is to say, a manuscript that contains the entire Christian Bible.

The Genesis cycle starts in the upper left corner with the Creation of Adam (Genesis 2:7) and ends with the Expulsion of Adam and Eve, who must now respectively suffer the pains of labouring on the land and of childbearing (3:16–24). These illuminations show a youthful Christ with long hair—rather than an older man with white hair and beard, typical of representations of God the Father—engaging with humanity’s first parents.

In deciding to represent the divine Artifex in this manner, the artist must have had the third verse of the Gospel of John in mind: ‘through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made’ (1:3), as well as those passages where Jesus states that ‘anyone who has seen me has seen the Father’ (14:9), and ‘I am in the Father, and the Father is in me’ (14:11).

By adding a representation of Christ at the beginning of the first book of the Christian Bible, medieval artists thus stressed Christ’s divine and eternal natures as well as the connection between the Old and New Testaments.

References

Hayward, C.T.R (trans.). 1995. Saint Jerome’s Hebrew Questions on Genesis (Oxford: Clarendon Press)

Kessler, Herbert L. 1971. ‘Hic Homo Formatur: The Genesis Frontispieces of the Carolingian Bibles’, The Art Bulletin 53.2: 143–60

Unknown Byzantine artist

Byzantine Icon of Christ, 11th–13th century, Miniature mosaic, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence; inv. No. 3, Scala / Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY

And the Word was God

Commentary by Jacopo Gnisci

The opening verse of the Gospel of John refers to Jesus as the ‘Word’, from the Greek logos, a title also used in the book of Revelation (19:13). In this verse, John says that the ‘Word was with God’ (1:1) to assert that Jesus—as one person of the Trinity—is not to be confused with the Father while yet also being indivisible from him.

In a biblical context, ‘Word’ can have various meanings. It can be used to refer to Christ himself or to a command or speech given by God. In Genesis, for example, God’s speech brings the world into existence (1:3–26); in Exodus God speaks in ‘words’ to give Moses his Commandments (20:1); and in the First Epistle to the Thessalonians Paul asserts that ‘when you received the Word of God, which you heard from us, you accepted it not as a human word, but as it actually is, the Word of God, which is indeed at work in you who believe’ (2:13).

Byzantine artists drew inspiration from the Bible, and especially the Gospel of John, to present sophisticated representations of what logos might encompass. This is showcased by this mosaic icon which was once in the collection of Lorenzo the Magnificent (Bacci 2008). The icon, which features a portrait of Jesus against a gold background, alludes to the Word of God in three ways: the tips of the middle and ring fingers of Christ’s right hand touch the tip of his thumb, in a gesture that symbolizes the voice of God (Trumble 2010: 54); his left hand holds an open Gospel book that stands for God’s written command; and, finally, Christ himself is proof that ‘the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us’ (John 1:14).

Each of these three elements stands in a metonymic relationship to the other components of the icon and to the Trinity as a whole. The gold tesserae of the icon reflect the light to draw in observers and remind them that Jesus as ‘the true light that gives light to everyone was coming into the world’ (John 1:9), while the cross in Christ’s halo foreshadows his Crucifixion which occurred because ‘the world did not recognize him’ (1:10).

References

Bacci, Michele. 2008. ‘Micromosaic with Christ Pantokrator’, in Byzantium, 330–1453, ed. by Robin Cormack and Maria Vassiliki (London: Royal Academy of Arts)

Trumble, Angus. 2010. The Finger: A Handbook (Victoria: Melbourne University Press)

Unknown Coptic artist

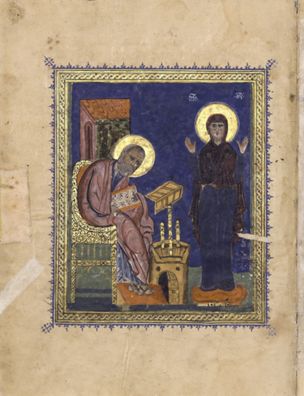

St John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary, from a Copto-Arabic Gospel, c.1204–05, Illuminated Manuscript, Vatican Library, Vatican City; Vat. Copt. 9, fol. 388v, © 2021 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana

He was in the World

Commentary by Jacopo Gnisci

The Gospel of John paints a somewhat different portrait of Jesus from the Synoptic Gospels—one that has distinctive and emphatic ways of highlighting his divinity. Jesus, the Gospel tells us in very direct terms, ‘was God’, and ‘was with God in the beginning’ (1:1–2).

Nevertheless, the prologue of John’s Gospel makes it clear that Christ is also a God who ‘was made flesh and made his dwelling among us’ (1:14). This Christ is inseparably divine and human.

Early Christian thinkers read John with great care to understand the relationship between Christ’s human and divine natures. Among these theologians was Cyril (Patriarch of Alexandria, in Egypt, 412–44). In his Commentary on John, Cyril demonstrated that the Son is equal to the Father in his divine nature and attacked those who argued otherwise. Meanwhile, in his treatises and letters, Cyril also frequently asserted Christ’s humanity by drawing on John 1:14.

Because Cyril believed that the Word was ‘born’ in flesh (John 1:14; 6:51–56), he also argued that his mother should be addressed with honorific titles such as ‘God-bearer’ (Theotokos) and ‘Mother of God’ (Meter Theou).

Cyril’s writings, which continue to be read and appreciated by Coptic Orthodox Christians in Egypt, may have inspired the painter of the Copto-Arabic Gospel book shown here. The manuscript was written at the Monastery of Saint Anthony at the Red Sea by a certain George in 1204–05 (Leroy 1974: 148–53). Each of the Four Gospels is introduced by a portrait of its author according to a tradition of book illuminations that dates back to late antiquity. John the Evangelist is dressed in a blue tunic and seated to the left of the scene. He holds a book which represents his Gospel and is inscribed with the first verse of John 1 to proclaim Christ’s divine nature.

But who is the figure with open arms to his right? The caption above her head identifies her as the Virgin Mary by addressing her with the same title used by Cyril of Alexandria: ‘Mother of God’. She is here to pray on behalf of the reader but also to prove that, through her, the Word was incarnated in Jesus Christ.

Combined, the figures of John and Mary announce Jesus Christ as perfect God (2 Corinthians 4:4) and perfect human (1 Corinthians 15:22).

References

Cyril of Alexandria. 2013. Commentary on John, vol. 1, ed. by Joel C. Elowsky, trans. by David R. Maxwell (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press)

Leroy, Jules. 1974. Les manuscrits coptes et coptes-arabes illustrés, Institut Français d’Archéologie de Beyrouth, Bibliothèque Archéologique et Historique 96 (Paris: Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner)

Russell, Norman. 2002. Cyril of Alexandria (London: Routledge)

Unknown French artist (Tours) :

The Genesis Cycle, from the Moutier-Grandval Bible , c.830–40 , Illuminated Manuscript

Unknown Byzantine artist :

Byzantine Icon of Christ, 11th–13th century , Miniature mosaic

Unknown Coptic artist :

St John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary, from a Copto-Arabic Gospel, c.1204–05 , Illuminated Manuscript

In Him was Life, and that Life was the Light of all

Comparative commentary by Jacopo Gnisci

The prologue to the Gospel of John features some of the most profound verses in the whole Christian Bible. In addition to considering the nature of Christ, it offers an overview of human history and describes our relationship with God.

Specifically, John tells us that Christ was the one through whom all things were created (1:3)—as illustrated by the Creation of Adam in the Genesis cycle of the Moutier-Grandval Bible—and that he brings life and light to all humanity (1:4)—which can be taken as a statement about his Incarnation and Resurrection.

Christ brings light to humankind because he himself is ‘the true light that gives light to everyone’ and because he ‘was coming into the world’ (1:9). To convey this message, the artist of the Bargello icon used gold tesserae and inscribed the book held by Christ with verses from the eighth chapter of John: ‘I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life’ (8:12). The book itself glimmers with the ‘light of the gospel that displays the glory of Christ, who is the image of God’ (2 Corinthians 4:4). The words on the book are in the first person and in the present tense to engage and reassure the viewer that God is eternally present. At the same time, the codex is open as an anticipation of his Second Coming (Matthew 24:34; Mark 13:30; Luke 21:32; Revelation 20:12). This is because, to use the words of Paul the Apostle, he ‘has now been disclosed and through the prophetic writings has been made known to all nations, according to the command of the eternal God, to bring about the obedience of faith’ (Romans 16:26).

Verses 10 and 11 of John 1 foreshadow the Passion—that is to say, Christ’s suffering and death on the cross which, for Christians, were necessary to save humanity from subjection to death. Within this scheme of salvation Christ must become ‘the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world’ (1:29). In a similar fashion, the orans posture of the Virgin Mary in the Copto-Arabic manuscript from the Monastery of Saint Anthony foreshadows the outstretched hands of her son who died on the cross to give us ‘the right to become Children of God’ (1:12).

The Gospel of John offers an elevated perspective on Jesus Christ, and, throughout the centuries, Christians of different denominations have turned to it to contemplate the mystery of God’s design and to understand the salvific implications of the Incarnation. The differences between the artworks considered in this exhibition show that its prologue is open to multiple readings. In fact, the three images considered in the individual commentaries were produced by artists working respectively for the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Coptic Orthodox Churches. These are churches that have been divided over theological issues, but they are united by their interest in this Gospel, and the desire to engage visually with its message.

For 'we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father' (John 1:14).

Commentaries by Jacopo Gnisci