John 10:22–42

Imaging the Trinity

Unknown English artist

The Trinity, from a Book of Hours, c.1501–10, Tempera on vellum, 330 x 240 mm, The British Library, London; Royal 2 B XV, fol. 10v, © The British Library Board

‘The Father and I Are One’

Commentary by Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen

In the context of being accused of blasphemy (on the grounds that he, a human being, had claimed to be God’s son) Jesus talks in John 10:22–42 about the nature of his relationship with God.

Although the word ‘Trinity’ does not occur in the Bible, significant New Testament references to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (cf. Matthew 28:18–20; 2 Corinthians 13:14, as well as this passage from John) gave rise to a Trinitarian notion of the divine—God is one, undivided and immutable in substance and yet lives and acts in the three persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Once the Christian faith had become the accepted religion of the Roman Empire under Constantine in the early fourth century, and Christian art and architecture began to flourish, visual artists began to grapple in earnest with this complex dogma.

This English sixteenth-century illumination is one of the most unusual, imaginative, and striking from the wide range of Trinitarian images in the history of Christian art. While the triandric motif (three male figures of identical appearance) was to develop as a type of Trinitarian iconography around the twelfth century, this composition is unique in its superimposition of the sun, its rays both covering and emanating from the Trinity, and pervading the whole page. While Father and Son look almost identical, so as to underscore their oneness and unity, the Holy Spirit’s body is rendered in white as a youthful figure, not uncommon in Trinitarian iconography—a pictorial attempt, it seems, to render the non-corporeal, pure, dynamic, ever-alive nature of the Spirit.

The divine light both is and springs from God and shines into the world with multiple tiny angels in red, like flames, and in white, like doves—references to the Holy Spirit and to divine love. The symbols of the four Evangelists are included in each corner. The illumination thus alludes to the one God, the creator God, to God as light of the world, to divine, kingly omnipotence (the crown), as well as to the proclamation of the good news (Evangelists) and thus indirectly to the divinely-inspired church on earth.

References

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=8712&CollID=16&NStart=20215 [accessed 14 July 2018]

Thiessen, Gesa Elsbeth. 2009. ‘Images of the Trinity in Visual Art’, in Trinity and Salvation: Theological, Spiritual and Aesthetic Perspectives, ed. by Declan Marmion and Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen (Oxford: Peter Lang), pp. 119–40

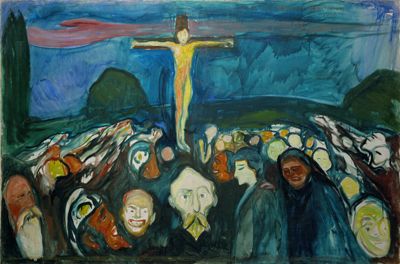

Edvard Munch

Golgotha, 1900, Oil on canvas, 80 x 120 cm, Munchmuseet, Oslo; © The Munch Museum / The Munch-Ellingsen Group / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY HIP / Art Resource, NY

A Heavenly Hand

Commentary by Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen

‘The works that I do in my Father’s name, they bear witness to me’, says Jesus in this passage (John 10:25; cf. 5:36).

There is a small element in Edvard Munch’s Golgotha that one might easily miss, and which may imply a Trinitarian dimension; the shape of an upturned hand seems to be suggested in the red cloud above Christ’s head. A hand emerging from the clouds is one of the oldest Christian symbols of God the Father. One could argue therefore that the image implies, as John 10:22–44 tells us, that the saving work of Christ the Son is at the same time of, with, and through the Father.

The absence of the Holy Spirit in this image is notable but, in fact, need not surprise. Even at the zenith of Trinitarian imagery in the Renaissance and Baroque, the Spirit is occasionally absent or barely visible as a tiny dove, hovering between the Father and the Son. Interestingly, this occasional neglect of the Holy Spirit in art is somewhat reflective of the history of Christian theology which has tended to focus more on Christ and the Father than on the Holy Spirit.

The Trinity is rarely depicted in modern art. However, this work by Munch—through its rendering of Christ on the Cross and the red cloud as an apparent allusion to the hand of God—offers an understated, subtle Trinitarian image of Christ who, in unison with his Father, does his Father’s works.

Unknown artist, Cusco School

Trifacial Trinity (Trinidad trifacial), c.1750–70, Oil on canvas, 182 x 124 cm, Museo de Arte de Lima, Peru; Memorial Memory Donation, V-2.0-0035, Album / Alamy Stock Photo

Teaching the Trinity

Commentary by Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen

‘…believe the works, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me and I am in the Father (John 10:38).

From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries the Cuzco School, an artistic movement in Peru, flourished. Its primary aim was to bring the Roman Catholic faith to the Inca. European Christian iconography was now inculturated into the ‘new world’.

Highly didactic, symbolic, and schematic, this image was intended to teach the basic truths about the Trinity. While some trinitarian images have proved capable of instilling a sense of mystery, depth, awe, and contemplation in the onlooker, this frontal image is somewhat flat and heavily laden with symbolism. Three identical interlinking faces are depicted on the Trinity’s head, behind which a haloed triangle reinforces the three-in-oneness, which then again is echoed in the large Scutum Fidei (or ‘Trinity Shield’), a thirteenth-century statement about the Trinity that has never been equalled for its brevity. The Trinity is framed by heavenly clouds and by the four Evangelists, thus connecting the Trinity with the biblical authority of the Gospels. The papal tiara at the bottom centre makes the link with the ‘true’—the Roman Catholic—Church through the centuries.

How ironic to include the papal tiara in the trifacial iconography which had, in fact, received papal condemnation, first by Urban VIII (1568–1644, pope from 1623) in the seventeenth century, and, over one hundred years later, by Benedict XIV (1675–1758, pope from 1740)! Images of this type were condemned not so much on dogmatic but on aesthetic–biological grounds as ‘monstrous’, offensive aberrations of nature.

The Cuzco painters, thousands of miles away from Rome, seem to have been little troubled by such worries. Aesthetic–artistic excellence and papal pronouncements were eclipsed by didactic–theological aspirations. Images such as these seem certainly to have fulfilled their intended purpose in teaching the ‘pagan’ Inca the Christian Trinitarian faith, just as they had previously succeeded in doing in medieval Europe.

Indeed, perhaps precisely by contradicting and going beyond what is ‘normal’ and natural, the rendition of the Trinity as a hybrid figure may have succeeded in conveying something of the transcendent otherness and mystery of the divine.

References

Brown, David. 2002. ‘The Trinity in Art’, in The Trinity: An Interdisciplinary Symposium on the Trinity, ed. by Stephen T. Davis, Daniel Kendall, and Gerald O’Collins (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 329–56

Thiessen, Gesa Elsbeth. 2018. ‘Not So Unorthodox: A Reevaluation of Tricephalous Images of the Trinity’, Theological Studies, 79.2: 399–426

Unknown English artist :

The Trinity, from a Book of Hours, c.1501–10 , Tempera on vellum

Edvard Munch :

Golgotha, 1900 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist, Cusco School :

Trifacial Trinity (Trinidad trifacial), c.1750–70 , Oil on canvas

‘The Father is in Me and I Am in the Father’

Comparative commentary by Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen

John 10:22–42 is one of the texts that early Christian theologians regarded as central when trying to understand how Christ related to the one God of Israel. This and other passages, including those elaborating on the role of the Holy Spirit (Matthew 28:18–20; John 3:5–6; 14:26), contributed to the emerging dogma of the Trinity in the fourth century. It is a doctrine that has occupied not only theologians but also artists ever since.

If the challenge of how to think about God as both one and three posed immense problems to theological reasoning, how much more difficult would this prove to be for artists, most of whom did not have the same theological training, faced with trying to image the mystery in painting and sculpture.

The three works in this exhibition span over four hundred years and three countries. One was completed in England in the epoch of the Renaissance and the Reformation. Another was executed as a Christian teaching-aid in mid-eighteenth-century Peru in just the period when—thousands of miles away in the ‘old world’ of post-Enlightenment Europe—the new critique of religion was making itself felt. The final image under discussion was completed in 1900 when what is now usually referred to as modern art was first establishing itself through the developments of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. It displays a more personal–subjective relation to its theme.

It has frequently been remarked that the nineteenth century was a time in which religious subjects were relegated to the margins of art. It was the age of Karl Marx, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Sigmund Freud, a time in which most leading artists manifested progressively less interest in Christian themes—despite notable exceptions such as the Pre-Raphaelites, the ‘Nazarenes’, and the Symbolists. Much religious art was now made by second- or third-rate artists who lacked imagination and the artistic brilliance required to create outstanding works of art with religious subject matter.

The eighteenth-century painting from Cuzco may help us to understand some of the reasons for this decline. With its strong didactic emphasis this, and other such works of the time, lack subtlety and spiritual depth.

The manuscript illumination from c.1510 and Edvard Munch’s work from 1900, on the other hand, convey something of divine mystery, artistic–theological imagination and feeling. The Book of Hours, an aid to devotional prayer, reveals the Trinity as embracing the whole universe by analogy with the way that the sun, a pre-Christian and Christian symbol of the divine, pervades all being with the divine light. Yet, at the same time this Trinity conveys the sense of divine transcendence and mystery in being mostly hidden by the superimposed sun. One might speculate that the image was painted by an imaginative illuminator—or commissioned by an imaginative patron—who was not afraid to be inventive, possibly even original, in trying simultaneously to capture both the inner relations of the Trinity as perichoretic (or mutually coinherent) and the ‘economic’ dimensions of the Trinity’s relation with creation.

The Cuzco work aimed to teach the Christian faith; the Book of Hours—made for Thomas Butler, 7th earl of Ormond (d. 1515) or possibly for another member of his family—was intended for personal meditation. Munch, four hundred years later—in an increasingly post-theocentric age, and having rejected his morbid Pietist Lutheran upbringing—operates in a rather changed context. His work, unlike the other two, is not intended to be used for religiously-didactic or explicitly devotional purposes. Without the external stimulus of a commission (from the Church or a wealthy Christian patron), Munch painted Golgotha on his own initiative, and from personal desire. The fact that he chose the archetypal Christian iconography of the Crucifixion and presented himself as the Christ figure makes evident that despite his rejection of the stifling Pietism he had experienced as a youth, he had apparently not lost his faith. On 8 June 1934 he wrote in his notebook:

I bow down before something which, if you want, one might call God—the teaching of Christ seems to me the finest there is, and Christ himself is very close to Godlike—if one can use that expression. (Bøe 1989: 29)

In its very personal rendition of the Crucifixion the work may be interpreted as a personal statement of belief, independent of the Church. Yet with its subtle hinting at the relations within the Godhead, it acknowledges, as John 10:22–44 does, something of the Christological–Trinitarian faith of Christianity.

References

Anderson, Jonathan A., and William A. Dyrness. 2016. Modern Art and the Life of a Culture: The Religious Impulses of Modernism (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Press)

Bøe, Alf. 1989. Edvard Munch (Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa)

Commentaries by Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen