Genesis 32:22–32

Jacob Wrestling the Angel

Jacob Epstein

Jacob and the Angel, 1940–41, Alabaster, Unconfirmed: 214 x 110 x 92 cm, 2500 kg, Tate; Purchased with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund, and the Henry Moore Foundation 1996, T07139, © The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein, Photo: © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

The Tensions of Encounter

Commentary by Natalie Carnes

Jacob Epstein’s sculpture Jacob and the Angel admits no easy interpretation of the biblical episode narrated in Genesis 32. Instead it provokes the viewer to look again, as each glance unsettles the conclusions of the last.

If the scriptural narrative of Jacob wrestling with the angel presents the reader with a series of tensions—Jacob prevails (32:25, 27) but the angel strikes the final blow (vv.31–2); the angel wounds Jacob (v.32) and the angel blesses Jacob (v.29); the angel is called both a man (vv.24–5) and the one by whom Jacob sees God face to face (v.30)—Epstein does not resolve those tensions so much as invite the beholder to contemplate them visually.

One of the heaviest objects in Tate’s collections at 2500kg, Epstein’s statue renders the figures of Jacob and the angel with wide proportions that visually emphasize their ponderousness. At the same time, the alabaster stone of which they’re made is almost translucent in places, capturing light in a way that gives the figures something of a weightless quality. Are the figures weighty or light? Material or immaterial? Earthly or heavenly?

And what are these subjects doing?

From some perspectives, their encounter appears erotic, as if the angel grips Jacob in an amorous embrace. Perhaps Jacob is reciprocating by pressing his body into the angel’s. Or perhaps the encounter is less reciprocal, less symmetrical. For, from other perspectives, the angel appears to hold Jacob up with his arms and bend his legs to support his weight as Jacob hangs limply, impotently. The angel’s heels rise from the ground, as if he is lifting Jacob up, whose heels also elevate slightly. Look again; is the angel bearing Jacob up or squeezing the last breath from him? Is this an embrace unto life or death?

The asymmetry of their agency in this perspective contrasts with the symmetry of their composition. By size and weight, Jacob and the angel are equals, and yet that equality, like all the tensions structuring this encounter, underscores their more fundamental inequality: that Jacob was never a match for this angel.

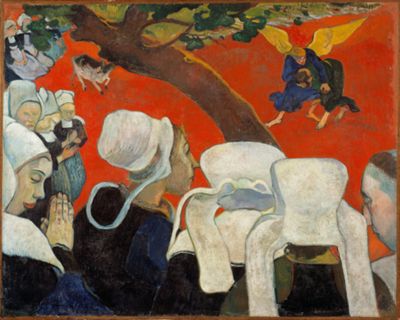

Paul Gauguin

Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel), 1888, Oil on canvas, 72.20 x 91 cm, National Galleries Scotland; Purchased 1925, NG 1643, Photo: © National Galleries of Scotland, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

The One Who Won’t Let Go

Commentary by Natalie Carnes

The ‘vision’ of Paul Gauguin’s painting is not literal, but spiritual. In a letter to Vincent van Gogh (September 1888), Gauguin points to the disproportionate smallness of the cow and the wrestlers in relation to the spectators. Such disproportionality signals, he explains, that the scene is taking place in the women's imaginations. And the women do not need physical organs to see a struggle in the imagination. In their encounter with the place named Peniel/Penuel (from the Hebrew panim, face and el, God)—so-called because there Jacob saw God face to face—the eyes of all would-be spectators are closed or obscured from us.

There is one notable exception. One woman, in what is almost the centre of the canvas, leans forward and gazes raptly at the battling figures, as if absorbed in the imaginary spectacle of human–divine contest. If this struggle is imaginary, what exactly does she see? Is she some kind of Doubting Thomas, attempting to assess divinity with her own senses? What kind of struggle to see is the gazing woman engaged in? The gazing woman’s size and centrality emphasize the significance of her presence. She shifts our sense of what we are engaged in as we view this scene, making us more aware of the possibilities and the limits of our seeing. As we stare open-eyed at this scene of divine encounter, she is like us, or we are like her. The gazing woman perhaps stands in for us in the painting, figuring for us our own struggle to see.

‘What does [Jacob’s] combat matter’, a phenomenologist asks, ‘if it cannot take place this very night?’ (Chrétien 2003: 8). Through the figure of the gazing woman, Gauguin’s painting invites the viewer into Jacob’s struggle with a partner identified as both a man (Genesis 32:24, 25) and the divine (v.28, implied in v.30), an ambiguity resolved in later texts that call the figure an angel (Hosea 12:4). The victory the text commends to us is to prevail, not by defeating God or God’s messengers, but by meeting the divine face to face, with our own eyes—to refuse, like Jacob holding the angel, like the woman holding her gaze, to let go until we have received our blessing.

References

Chrétien, Jean-Louis. 2003. Hand to Hand: Listening to the Work of Art, trans. by Stephen E. Lewis (New York: Oxford University Press)

Gauguin, Paul. 1888. ‘Letter 688, to Vincent van Gogh, c.26 September 1888’, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, inv. nos. b847 a-d V/1962, available at http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let688/letter.html [accessed 25 January 2020]

Herban III, Mathew. 1977. ‘The Origin of Paul Gauguin’s Vision after the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1888)’, The Art Bulletin 59.3: 415–20

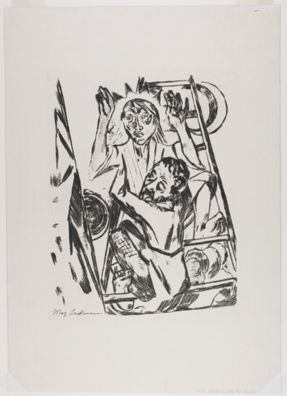

Max Beckmann

Jakob Ringt mit den Engel (Jacob Wrestles with the Angel), 1920, Drypoint on medium, slightly textured cream laid paper, 288 x 222 mm, The Portland Art Museum; The Vivian and Gordon Gilkey Graphic Arts Collection, 80.122.391, Courtesy of the Portland Art Museum

Ascending with Angels

Commentary by Natalie Carnes

Into the story of Jacob wrestling with the angel at Peniel/Penuel (face of God in Hebrew), Max Beckmann drops a second scene: Jacob’s dream of angels ascending and descending at Bethel (house of God in Hebrew). That the scenes are combined we may find intriguing, and the way they are combined, more intriguing still.

In the top third of the print, a haloed angel stares toward some distant horizon as if unbothered by the action in which it is entangled. The angel has raised its hands in a gesture of praise that also mimics a gesture of surrender, but it seems neither exultant nor anxious. Positioned in front of the ladder, the angel is still. This section of the print is, overall, uncluttered, dominated by the power radiating from the angel’s face.

The bottom two-thirds of the print are much busier. That section is dominated by Jacob’s contorted body, holding on to the angel for dear life, as if he is hoping to ascend with it. Is this the blessing Jacob seeks? It is clear, at least, that whatever blessing or glory he receives from this encounter will not be from his own strength but from his persistence in hanging on to divine life.

The angel, too, is moving in the bottom portion of the print. In contrast to his head and chest in the top third of the print, his legs seem to be behind the ladder, his bare feet gripping the rungs. Despite the appearance of stillness in the upper half, this angel is propelling himself upward.

The viewer’s eyes ascend the long line of Beckmann’s ladder up toward the top section of the print, toward the angelic face, unmoving and ringed with glory. In following this path, they imitate Jacob, as he holds on to the divine messenger in determined hope of blessing.

Jacob Epstein :

Jacob and the Angel, 1940–41 , Alabaster

Paul Gauguin :

Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel), 1888 , Oil on canvas

Max Beckmann :

Jakob Ringt mit den Engel (Jacob Wrestles with the Angel), 1920 , Drypoint on medium, slightly textured cream laid paper

Divine Striving

Comparative commentary by Natalie Carnes

The scriptural account of Jacob wrestling interrupts the story of Jacob meeting Esau after years of estrangement. Jacob sends presents to Esau by messengers on the day before their encounter (Genesis 32:3–21); he wrestles that night (vv.22–32); and he meets Esau after daybreak on the following morning (33:1–17). In this way Jacob’s wrestling partner seems to be a figuration of Esau, the brother with whom Jacob has struggled over the course of his life.

But the partner is not so simple to identify. As it begins to narrate the night-time struggle, the text says only that he wrestled with ‘a man’ (32:24–5). By the end of the encounter, Jacob claims he has seen ‘God face to face’ (v.30). Encompassing both possibilities, the wrestling partner says in the text that Jacob has ‘striven with God and with humans’ (v.28). At some point, the tradition emerged of understanding this wrestling partner as an angel (Hosea 12:4), which is how the story is most often remembered.

Scripture slips between different narrations of Jacob’s wrestling partner, as if registering some anxiety about how to identify his opponent. What could it mean, after all, to wrestle with God or God’s emissaries, particularly when the text claims that Jacob prevailed? This God who can be defeated by a human seems to lack the almightiness attributed to the God of Jewish and Christian tradition. This picture of God is certainly difficult to hold together with claims that God’s power is so great and so wholly other that our own cannot compete with it.

This problem of how to understand an all-powerful God whose emissary can yet be defeated by a human generates divergent artistic responses.

Jacob Epstein’s sculpture represents a struggle between Jacob and a winged angel, but it minimizes Jacob’s agency. However matched Epstein’s Jacob is to the angel in terms of size, he is no equal partner. Epstein’s Jacob slumps in the angel’s arms, which bear him up. His head falls back, as if in sleep or unconsciousness. Without the angel’s support, he would collapse to the ground. This Jacob is no competitor when faced with the strength of the Lord; his strength is from the Lord. From some angles, the angel may be seen to treat Jacob as an adversary, but his embrace is also tender, even erotic. The strength he gives Jacob may stem from a loving intimacy with him.

Where Epstein resolves the problem of divine wrestling by minimizing Jacob’s agency, Max Beckmann addresses it in the opposite way, by maximizing it. Beckmann’s Jacob clings to an angel whose face is ringed in glory and whose gaze focuses on some distant scene, or maybe on the viewer of the work itself, in another time and place. Beckmann’s angel does not register Jacob’s presence at all. Jacob, by contrast, clings to the angel, wrapping his body around the angel’s. His stubborn grasp on the angel recalls Scripture’s description of Jacob refusing to let go until the angel blesses him (32:26). But in this case, the angel blesses him without seeming to notice him. Clutching the angel, Jacob ascends the ladder with him, carried to God by the angel’s own power. Beckmann’s Jacob is no more a competitor with divine power than Epstein’s.

Paul Gauguin’s painting reinterprets the episode by relocating the primary action. The angel is easily defeating Jacob, but the wrestling match takes up only the top right corner of the canvas. The largest figures in the painting, those in the foreground, are the women engaging in the vision of their collective imaginations after the sermon which the painting’s title suggests they have just heard. The central woman, with her eyes wide open as she leans forward, seems to be attempting to see the scene with her eyes. Gauguin’s painting might be understood as relocating the central struggle from Jacob and the angel to the woman striving to see the divine in the world, labouring for her own Peniel, where she, like Jacob, can see God face to face. She therefore bears the struggle forward to the viewer, inviting her also to enter into her own struggle for divine sight.

The divine in all of these paintings is powerful, unthreatened by human striving. Human striving, in fact, becomes a way to lay hold of the divine, to enter into greater intimacy with the divine, to ascend to divine blessing, and to discern the divine in the world. What the human experiences as struggle, God takes as an opportunity to bestow divine presence.

References

Chrétien, Jean-Louis. 2003. Hand to Hand: Listening to the Work of Art, trans. by Stephen E. Lewis (New York: Oxford University Press)

Herban III, Mathew. 1977. ‘The Origin of Paul Gauguin's Vision after the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1888)’, The Art Bulletin 59.3: 415–20

Commentaries by Natalie Carnes