Genesis 37:13–36

Joseph Is Sold

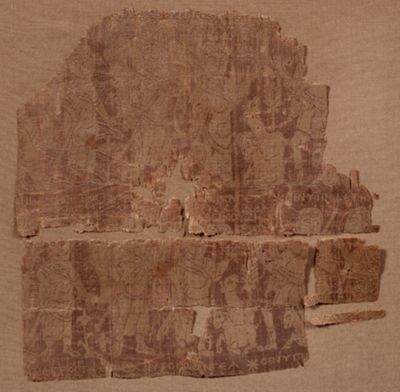

Unknown artist

Joseph sent to Sechem by Jacob, 5th or 6th century, Silk, (a) 11.4 x 17.5 cm, (b) 7.1 x 14.7 cm, (c) 4 x 4.4 cm, Trésor de la cathédrale de Sens; Inv. TC B 36, Photo: E. Berry, © Musées de Sens

A Coat of Many Colours?

Commentary by Henry Maguire

This fragmentary silk, now in three pieces and faded, but originally coloured yellow and purple, was woven in the fifth or sixth century, perhaps in Syria or Egypt (Weitzmann 1979: 462–63; Durand 1992: 152). It portrays the same scenes from the life of Joseph as the miniature in the Vienna Genesis featured elsewhere in this exhibition (Genesis 37:13–20), but in an abbreviated form.

The individual episodes were repeated one above the other in successive registers of the weaving. At the far left of the upper register only the legs of the seated Jacob have survived. Immediately to the right Joseph stands and looks back at his father as he receives his mission. The next episode of the story is shown by just one figure, representing the man who gave Joseph directions to find his brothers with their flocks. The stranger holds a long staff and points the way with his left hand. On the right Joseph is received upon arrival by two of his brothers, who stand among their sheep. Joseph is portrayed as somewhat shorter than his siblings, to show that he is still a child.

An inscription in Greek identifies each of the scenes. The one above the reception of Joseph by his brothers reads: ‘The dreamer approaches. Now, therefore, come, let us kill him’.

The silk was woven on a drawloom, which, with its mechanically produced sequences, enabled the exact repetition of motifs in series. In this case the same scenes appeared in identical form in at least three registers. We do not know the original function of the silk. It is very possible that it was part of a garment, since a fourth-century bishop named Asterius of Amaseia, in northern Türkiye, complained of people who appeared in public dressed in silks woven with biblical scenes, hoping to win the favour of God (Mango 1972: 50–51). Such clothes were more than merely functional or ornamental; they were expressive of faith in Christian salvation.

References

Durand, Jannic (ed.). 1992. Byzance: L’art byzantin dans les collections publiques françaises (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux)

Mango, Cyril. 1972. The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312–1453: Sources and Documents (Englewood Cliffs: University of Toronto Press)

Weitzmann, Kurt (ed.). 1979. Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

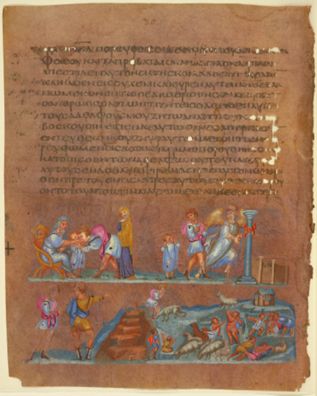

Unknown artist

Joseph sent to Sechem by Jacob, from the Vienna Genesis, 6th century, Illuminated manuscript, Österreichische Nationalbibliotek, Vienna; Cod. theol. gr. 31, Courtesy of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

Behold This Dreamer Cometh

Commentary by Henry Maguire

The Vienna Genesis is a sumptuous sixth-century manuscript (Zimmermann 2003). Approximately half of each of its purple dyed pages contains text excerpted from the Bible, while the other half displays an illustration.

On the page exhibited here, the painting portrays Jacob sending the young Joseph out to visit his brothers, who are tending their flocks at Shechem (Weitzmann 1977: 80). The artist tells the story in a novelistic manner, with an emphasis on human emotion. At the upper left of the miniature, the father tenderly sends the beloved son of his old age on his mission. As he departs, Joseph bends down to kiss the youngest of his brothers—and the only one with whom he shares a mother—the child Benjamin. On the right, Joseph is led on his way by an angel, not mentioned in the biblical text. As he goes, Joseph turns to give a farewell glance at little Benjamin, who stands crying behind him. At the bottom left, Joseph is told where to find his brothers by a man whom he meets in a field (Genesis 37:15–17). At the bottom right Joseph’s brothers gesticulate excitedly toward Joseph, as they see him approaching from behind a hill at the upper left of the scene.

According to the biblical text, even when the brothers spied Joseph from afar, they were already plotting to kill him, saying to each other ‘Behold this dreamer cometh’ (Genesis 37:18–20). Joseph’s two dreams, which forecast his dominion over his family, had been described earlier in the chapter. In the first, the brothers were binding sheaves in a field, when Joseph’s sheaf stood upright and his brother’s sheaves made obeisance to it (vv.5–7). In the second dream, the sun, the moon, and the eleven stars all bowed down to Joseph (v.9). These dreams caused the brothers to resent Joseph, as did the favouritism shown to him by their father, exemplified by the gift of a coat of many colours (vv.3–4).

References

Weitzmann, Kurt. 1977. Late Antique and Early Christian Book Illumination (London: Chatto & Windus)

Zimmermann, B. 2003. Die Wiener Genesis im Rahmen der antiken Buchmalerei (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag)

Unknown Egyptian artist

Roundel Illustrating Episodes from the Biblical Story of Joseph, 7th century, Linen, wool; tapestry weave, Diam.: 26.1 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Charles K. and Irma B. Wilkinson, 1963, 63.178.2, www.metmuseum.org

A Story that Comes Full Circle

Commentary by Henry Maguire

This textile roundel was produced in Egypt, probably in the late sixth or the seventh century (Friedman 1989: 160; Stauffer 1995: 37). It is woven in coloured wools on a plain undyed linen ground, a cheaper medium than silk. The roundel illustrates almost the whole of Genesis 37, thus expanding the story of Joseph that is shown in the Vienna Genesis manuscript and in the silk at Sens (both also in this exhibition).

At the upper left of the circle Jacob, seated on a throne, sends Joseph out to join his brothers at Shechem. Joseph appears as a child, as he does in all of the subsequent scenes. Just to the left appears a man who is either the stranger giving Joseph directions, or one of his siblings receiving him. Then, reading in a counter-clockwise direction, we see a brother putting Joseph in the well, having stripped him of his coat of many colours. At the bottom of the roundel the brothers dip the coat in the blood of a goat, before selling Joseph to a dark-skinned Midianite. To the right Reuben laments beside the empty well. At the far right, Joseph is transported to Egypt on the back of an animal, before being sold by a Midianite to Potiphar. These episodes encircle a small central medallion illustrating the second dream that caused the brothers’ envy, namely the personified sun and moon, and the eleven stars all bowing down before the sleeping Joseph (Genesis 37:9).

This roundel belongs to a large group of similar pieces woven with the same cycle of scenes taken from Genesis 37 (Abdel-Malek 1980; Fluck 2008). The majority were either medallions, placed at the shoulders and knees of tunics, or they were sleeve bands or vertical bands located on the bodies of the garments. Typically, they were woven in sets, so that the same imagery would have been repeated several times on the same piece of clothing. It is evident that some of these tunics were given to children, so that the child-like appearance of Joseph in the weavings would have been appropriate for the age of the wearer. Not only did the roundel adorn a garment with colour, but it was interwoven with spiritual significance, for the story of Joseph was seen as a prefiguration of the life of Christ; Joseph’s rescue from the well and his eventual rule over his brothers embodied the message of Christ’s triumph through the Resurrection.

References

Abdel-Malek, Laila H. 1980. ‘Joseph Tapestries and Related Coptic Textiles’ (Unpublished PhD, Boston University)

Fluck, Cäcilia. 2008. Ein buntes Kleid für Josef: Biblische Geschichten auf ägyptischen Wirkereien aus dem Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Berlin (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

Friedman, F. D. (ed.). 1989. Beyond the Pharaohs: Egypt and the Copts in the 2nd to 7th Centuries AD (Providence: Rhode Island School of Design)

Stauffer, Annemarie, et al. 1995. Textiles of Late Antiquity (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Unknown artist :

Joseph sent to Sechem by Jacob, 5th or 6th century , Silk

Unknown artist :

Joseph sent to Sechem by Jacob, from the Vienna Genesis, 6th century , Illuminated manuscript

Unknown Egyptian artist :

Roundel Illustrating Episodes from the Biblical Story of Joseph, 7th century , Linen, wool; tapestry weave

Joseph and the Saving Power of Christ

Comparative commentary by Henry Maguire

In the early Byzantine world of the fourth to seventh centuries, the episodes described in Genesis 37 were associated above all with the power of Christ to overcome the malice caused by envy. Early Christian commentators singled out two passages from biblical history that are particularly relevant to the evil consequences of envy: the story of Cain and Abel, and the story of Joseph and his brothers. Of these, the early life of Joseph was the more frequently illustrated in early Byzantine art.

The textile roundel in New York shows at its centre the dream of the sun, moon, and stars that was both an initial cause of the envy of Joseph’s brothers, and also a forecast of his future triumph over them. The narrative that encircles this image begins with Jacob sending Joseph out to Shechem to join his jealous brothers (Genesis 37:13–14), the episode that was also illustrated in the silk at Sens and in the painting of the Vienna Genesis. In addition, the weaving from the Metropolitan Museum of Art portrays the remaining events described in Genesis 37: the casting of Joseph into the pit, his brothers selling him to the Midianites, and the Midianites selling him to Potiphar.

The story of the suffering caused to Joseph by his brothers’ envy, and of his eventual dominance over them, was interpreted by early Byzantine commentators as a type, or prefiguration, of the life of Christ. In the late fourth or early fifth century the Syriac author Balai composed a sermon ‘On envy or on the reason for which the just Joseph was sold by his brothers’. At the beginning of this homily, the preacher calls upon Christ directly to aid him in his task: ‘O you who figured your type in Joseph, give me the means to declare his splendid deeds’ (Lamy 1889: 255–56).

A commentary by the fifth-century theologian Cyril of Alexandria spells out the parallels between the histories of Joseph and of Christ in more detail. Cyril says that the coat of many colours represented the many-faceted divine power in which Christ was clothed by his father, the power to cleanse lepers, to raise the dead, and to calm storms at sea. It was this divine power that drove the Pharisees to envy, just as it provoked the brothers of Joseph to jealousy. The Pharisees killed Christ and cast him into hell, as if into a well. But Christ returned to life from the dead, just as Joseph was raised from the empty well (Migne 1857–66, vol. 69, cols. 301–05).

A later commentary, written by Procopius of Gaza, also compares the brothers to the Pharisees who put Christ to death. He says that the Pharisees envied Christ because his father clothed him in a cloak of many colours—that is, in life and light which raised the dead and commanded the sea. Because of the signs and miracles of Christ, the Jews were consumed by the fire of envy (Migne 1857–66, vol. 87, 1, cols 471–72).

Two of the objects in the exhibition, the Vienna Genesis and the silk preserved in Sens, are luxury products, destined for use by the top level of society. The wool and linen tapestry weave in New York, on the other hand, belongs to a more modest social class, able to afford brightly dyed clothing, but not among the elite. Both the silk and the tapestry weave, however, demonstrate how the concepts of theology could inform daily life. The focus on the episodes from Genesis 37 in the figured textiles, together with the scattering of small crosses in the background of the roundel in New York, suggest that the wearers of these garments were well aware of the typology that connected Joseph with Christ.

In the early Byzantine period everybody, rich and poor, was frightened of envy, or the malevolence of a jealous gaze, whether it was directed by a neighbour or by the devil himself (Dickie 1995). Envy could cause all kinds of misfortune, ranging from sickness to death. This fear of envy made the story of Joseph and his brothers particularly relevant to overcoming the dangers of day-to-day existence. The tunics with their brightly dyed woollen roundels and bands imaged Joseph’s coat of many colours, in which the faithful enveloped themselves and their children.

The weavings on these colourful garments celebrated Joseph’s eventual triumph over envy and malice, a victory that also was a prefiguration of the miraculous and saving power of Christ.

References

Abdel-Malek, Laila H. 1980. ‘Joseph Tapestries and Related Coptic Textiles’ (Unpublished PhD, Boston University)

Dickie, Matthew W. 1995. ‘The Fathers of the Church and the Evil Eye’, in Byzantine Magic, ed. by Henry Maguire (Washington, DC: Harvard University Press), pp. 9–34

Lamy, T. J. (ed.). 1889. Sancti Ephraem Syri hymni et sermones, vol. 3 (Mechelen: H. Dessain)

Migne, J.-P. (ed.). 1857–66. Patrologiae cursus completus, Series Graeca, 161 vols (Paris)

Commentaries by Henry Maguire