Luke 1:26–38

The Annunciation

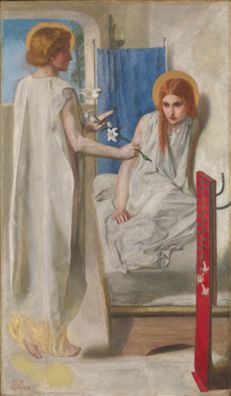

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation), 1849–50, Oil on canvas, Tate; Purchased 1886, N01210, © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

A White Annunciation

Commentary by Dillian Gordon

The Pre-Raphaelites frequently depicted the Annunciation, often dense with symbols, but of the traditional symbols Dante Gabriel Rossetti has chosen to eschew all but two—lilies and a white dove. Gabriel carries a simple stem of lilies, referring to the purity of the Virgin, and lilies decorate a red hanging, identical to the one the Virgin embroiders in Rossetti’s The Girlhood of Mary (Tate Gallery, N04872), painted around the same time. The dove of the Holy Ghost has flown in through the open window as if by chance and has the merest suggestion of the ring of a halo around its head.

Rossetti has dispensed with all finery. Behind the Virgin is a plain blue hanging, rather than the traditional cloth of honour. Gabriel, dressed in a simple white shift, has no wings: the only indication that he is an angel is the faint glow around his head (according to Rossetti himself ‘a gilt saucer’ ; Fredeman 2002: 228–29) and the small flames flickering above a pool of light which support his airborne feet. He casts a shadow over the bed, presumably the ‘power of the most High’ (Luke 1:35) overshadowing the Virgin. She too is dressed in a simple white shift. A young girl with loose hair, rather than a young woman, she seems to cower troubled in the corner of her bed, her eyes fixed almost trance-like, not on Gabriel, but on the stem of lilies pointing at her womb.

Only the minimal symbols—the word ‘March’ written in the bottom left-hand corner referring to the month of the Annunciation, and the title itself—clarify the subject of the painting. It was originally designed as a pendant to the Death of the Virgin which was never painted, and in fact death, rather than birth, is what the Virgin seems to be contemplating.

Rossetti’s brother was the model for Gabriel and his sister for Mary, but he would no doubt have been mindful of the fact that Gabriel was his own name saint.

References

Fredeman, William E. (ed.). 2002. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Formative Years, 1835–1862, Vol. I (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer), pp. 228–29

Surtees, Virginia. 1971. The Paintings and Drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882): A Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. I [Text] (Oxford: Clarendon), pp. 12–14

Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi

The Annunciation, 1333, Tempera on wood, gold leaf, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence; Inv. 1890 nos. 451, 452, 453, Scala / Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY

The Angel’s Greeting

Commentary by Dillian Gordon

The Sienese painter Simone Martini, has painted the moment when the Archangel Gabriel has just alighted on earth with soaring peacock wings. His golden cloak knotted around his neck still swirls in flight, the laces fastening his jewelled coronet still fly through the air. He is crowned with olive leaves and holds a fruit-bearing olive branch, symbolizing peace. With an elegant forefinger he indicates the dove of the Holy Ghost borne in a golden sphere by cherubim and seraphim. Before him the vase of white lilies refers to the purity of the Virgin.

‘Troubled’ (v.29), she shrinks from him, drawing her cloak around her, inclining her head so that the words from his mouth AVE MARIA GRATIA PLENA DOMINUS TECUM rendered in raised letters of gilded gesso go directly to her ear. Mary is careful to keep her place in the book she has been reading, traditionally the book of Isaiah: immediately above her in the roundel contained within the nineteenth-century frame is the prophet Isaiah with the text from his prophecy Ecce Virgo Concipiet, while the texts of three other prophets, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel (all interpreted in Christian tradition as referring to the virgin birth) are also included. Further texts from Luke 1:30, 31, and 35 are inscribed on Gabriel’s stole, and his name is inscribed on his sleeve.

The texts would have resonated with the clergy of Siena Cathedral for which this altarpiece was painted, and lay worshippers would have enjoyed the sheer beauty of the surface textures. The eye is invited to linger over the chequered Tartar silk, the multi-coloured marble floor, Gabriel’s cloth-of-gold dalmatic with its pattern of flowers and leaves, the radiant tooled haloes, the throne of intarsia (a speciality of Sienese woodworkers), the cloth-of-gold hanging over the throne, the realistically painted lilies (nowadays also known as Madonna lilies).

References

Cecchi, Alessandro et al. (ed.). 2001. Simone Martini e l’Annunciazione degli Uffizi (Milan: Silvana)

Martindale, Andrew. 1988. Simone Martini: Complete Edition (Oxford: Phaidon), pp. 187–190

Filippo Lippi

The Annunciation, 1450–53, Tempera on wood, The National Gallery, London; Presented by Sir Charles Eastlake, 1861, NG666, © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Openings

Commentary by Dillian Gordon

Filippo Lippi, as a Carmelite friar, would have been well-versed in Luke’s description of the Annunciation which he painted at least thirteen times. In this version the youthful Angel Gabriel has long since arrived and appears to float above the flowered lawn. His lowered feathered peacock wings follow the contours of the painting. The only movement is the white dove of the Holy Ghost fluttering towards the Virgin in a spinning spiral of shimmering golden light, sent by the hand of God emerging from the cloud of Heaven which overshadows the Virgin. She lowers her gaze in her submission as handmaid to the Lord, according to his word. Her right hand rests above her womb where a slit in her dress emanates golden rays, intimating the moment of conception. In the background the tiled floor leads towards her bed. The enclosed garden and lilies refer to the purity of the Virgin. The urn of lilies on the balustrade is carved with three feathers within a diamond ring, a symbol of the Medici family.

For this was painted for a secular setting, probably the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence. It was probably an overdoor, along with the pendant showing Seven Saints relevant to the Medici family (also in the National Gallery, London, NG667). Both paintings were subtly linked by Saint Cosmas in the latter work looking up and across at the hand of God in the Annunciation, and John the Baptist looking down and across to the Annunciation’s Holy Ghost, shown here in the form it would take when descending at Christ’s Baptism.

The Annunciation was an extremely popular subject in Florence. Not only was there a miracle-working fresco of the Annunciation in Santissima Annunziata, but the Florentine year began on 25 March (the feast of the Annunciation). Annual theatrical performances of the Annunciation took place, with God the Father in the storey above, and an angel lowered on pulleys into a special construction representing the house of the Virgin.

References

Gordon, Dillian. 2003. The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings, Vol. I, National Gallery Catalogues (London: National Gallery), pp. 142–55 (with further bibliography)

Newbigin, Nerida. 1996. Feste d’Oltrarno: Plays in Churches in Fifteenth-Century Florence, Vol. I (Florence: Olschki), pp. 1–43

Dante Gabriel Rossetti :

Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation), 1849–50 , Oil on canvas

Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi :

The Annunciation, 1333 , Tempera on wood, gold leaf

Filippo Lippi :

The Annunciation, 1450–53 , Tempera on wood

Phases of the Annunciation

Comparative commentary by Dillian Gordon

In his commentary on Luke, the Franciscan theologian Saint Bonaventure (d. 1274) distinguished three phases in the Annunciation.

Simone Martini’s painting shows the first and second: Gabriel’s arrival and greeting, emphasized by the words from Gabriel’s mouth which reach the ear of the troubled Virgin, and the role (ministerio) of Gabriel, unusually carrying an olive branch, symbol of peace, to announce the reconciliation of God the Father with humankind after the First Fall.

Filippo Lippi shows the third phase: the moment of the Incarnation and the response of the Virgin, when she submits to the word of God.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti titled his painting as the Virgin’s response: Ecce Ancilla Domini!. However, he subsequently changed the title to simply The Annunciation, to avoid any suspicion of covert Roman Catholicism.

In order to show the Holy Ghost coming upon Mary, the three versions use the traditional symbol of a white dove (used also by painters of the Trinity and Pentecost), deriving from the descriptions in the Gospels of the Holy Ghost descending in the form of a dove at Christ’s Baptism (Matthew 3:16; Mark 1:10; Luke 3:22; John 1:32).

Depicting the Incarnation was another challenge for painters. In some versions of the Annunciation a baby was shown sent from Heaven down streaming rays of light. Instead, Lippi symbolizes the conception as tiny rays of light emanating from the slit in the Virgin’s dress next to her womb which respond to the rays of light emanating from the dove, while Rossetti shows the stem of lilies pointing towards her womb.

These paintings were painted to serve very different functions.

Simone Martini’s altarpiece was commissioned for a specific altar in Siena Cathedral dedicated to Saint Ansanus, one of Siena’s patron saints, hence Saint Ansanus opposite Saint Massima, his mother, on either side of the central narrative. The altarpiece was the first of four altarpieces depicting scenes from the Life of the Virgin. The others were the Birth of the Virgin by Pietro Lorenzetti, the Purification of the Virgin by his brother Ambrogio, both painted in 1342, and the Nativity by Bartolomeo Bulgarini in 1351. They would have been accessible to both clergy and lay worshippers alike, with Simone’s a highly suitable altarpiece in front of which to say a rosary of ‘Hail Mary’ prayers.

Lippi’s painting on the other hand was commissioned for a private residence. Its precise location in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi is unknown. Nor is it certain which member of the Medici family commissioned it. Whatever the case, the secular patron ensured that his personal devotion was an integral part of the composition through the inclusion of the Medici emblem of a diamond ring and three feathers.

Such differing functions invited different treatment. Simone’s altarpiece would have been seen in the dark cathedral interior, lit by sporadic sources of light, candles in particular. So Simone created a surface most effective in catching the light, with tooled haloes and shimmering textiles. Lippi included a wealth of visual detail in the garden and palace interior to interest a secular patron.

Rossetti’s painting was not an individual commission. When he sold it to Francis McCracken of Belfast, he wrote in January 1853: ‘I have got rid of my white picture to an Irish maniac’, and called it a ‘blessed white eye-sore’ and ‘blessed white daub’ (Fredeman 2002: 224, 228–29). When exhibited in 1850 it had been criticized for ‘ignoring all that has made the art great in the works of the greatest masters’ (Treuherz et al. 2003: 148). However, Rossetti’s treatment of the subject was deliberately reductive, using only primary colours and simple outlines. He described it in April 1874 as having an ‘ideal motive for the whiteness’ (Fredeman 2007: 443), presumably intended to convey the purity of the subject. And although the Pre-Raphaelites admired medieval and Renaissance painters, Rossetti’s approach to a traditional religious subject could not have been more different.

His painting is stark, devoid of decoration. Gabriel has no wings at all, whereas Simone and Lippi gave Gabriel elaborate peacock wings. In Rossetti’s painting the Virgin’s bed is plain wood, the mattress resting on a mat of woven rushes, and the cloth of honour a simple blue hanging. The Virgin’s bed in Lippi’s version of almost exactly 500 years later is a faithful rendering of a Florentine Renaissance bed, complete with bolster and a richly patterned cover, while both Simone and Lippi render the cloth of honour as a beautifully patterned textile. There could not be a greater contrast than between the Virgin’s white shift in Rossetti’s painting and the Virgin’s mantle in Lippi’s, with its leaf-shaped silver-gilt buttons and panel of pseudo-kufic embroidery at the neckline. While Lippi depicts the humility of the Queen of Heaven, Rossetti has emphasised her simplicity and her humanity.

References

Cecchi, Alessandro et al. (ed.). 2001. Simone Martini e l’Annunciazione degli Uffizi (Milan: Silvana), pp. 16–19, esp. p. 17

Fredeman, William E. (ed.). 2002. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Formative Years, 1835–1862, Vol. I (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer), nos. 53.1, p. 224; 53.6, pp. 228–229; 53.7, p. 229

———. 2007. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Last Decade, 1873–1882, Vol. VI (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer), no. 74.85, p. 443

Surtees, Virginia. 1971. The Paintings and Drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882): A Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. I [text] (Oxford: Clarendon), pp. 12–14

Treuherz, Julian et al. 2003. Dante Gabriel Rossetti:1828–1882 (London: Thames & Hudson), pp. 19–23, and Cat. No. 13, p. 148

Van Os, Henk. 1984. Sienese Altarpieces 1215–1460, Vol. I (Groningen: Bouma’s Boekhuis), pp. 77–89

Commentaries by Dillian Gordon