Genesis 3:16, 20; 4:1–2

Eve’s Punishment

Damien Hirst

Mother and Child (Divided)–Installed at Tate Modern, 2012, Exhibition Copy 2007 (original 1993)–Installed at Tate Modern, 2012, Glass, painted stainless steel, silicone, acrylic, monofilament, stainless steel, cow, calf and formaldehyde solution, Two parts, each (calf): 113.6 x 168.9 x 62.2 cm; Two parts, each (cow): 208.6 x 322.5 x 109.2 cm, Tate; T12751, © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved DACS / Artimage, London and ARS, NY 2018. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Our First Mourning Mother

Commentary by Holly Morse

Damien Hirst’s Mother and Child (Divided) arguably confronts us with a stark subversion of traditional artistic representations of the Holy Mother, Mary, and Child, Jesus.

The work might be described as a bisected mother cow and her calf, separated for eternity, preserved at a painful distance from one another, suspended in formaldehyde. These are unavoidably mortal bodies, representing both the potential of life in their parent–child connection, but also the inescapability of death. Yet, in creating this visceral and moving piece of work that could be interpreted as challenging idealized images of holy maternity, Hirst seems to produce a profound meditation on maternal suffering that in many ways embodies the experience of the first mother, Eve.

This image appears to speak of the fracturing of community, love, and identity that is central to the story of the first human couple in Genesis 2–4, and in particular for the first woman as she is described in Genesis 3:16 and 3:20. In these texts, following her consumption of the Fruit of the Knowledge of Good and Bad, Eve becomes alienated. She is alienated from the man who is with her: he will now ‘rule over her’. She is alienated from her maternal body: she will now give birth in pain. And she is alienated from God: she is now barred from his Garden.

In particular, I believe Eve’s ‘pain in childbearing’ (v.16) is illuminated through Mother and Child (Divided). Although traditionally the pain that she is to endure during childbirth has been associated with physical labour, the Hebrew word issabon—from which the translations ‘pain’ or ‘pangs’ are taken—is more closely associated with the existential struggle of motherhood. This is the kind of sorrow that is alluded to in Genesis 4 when Eve’s first son, Cain, murders her second son, Abel. Although the biblical text provides no details of the pain Eve would have endured at this rupture in her family, reading this chapter of the Bible alongside Hirst’s image might encourage us to empathize with the first woman.

References

Manchester, Elizabeth. 2009. ‘Mother and Child (Divided)’, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hirst-mother-and-child-divided-t12751 [accessed 26 October 2018]

Meyers, Carol. 1988. Discovering Eve: Ancient Israelite Women in Context (New York: Oxford University Press)

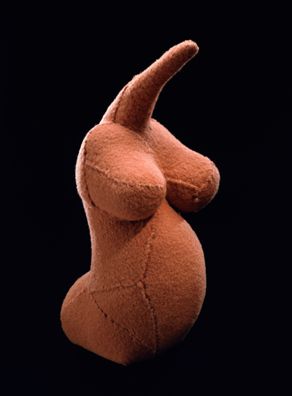

Louise Bourgeois

Fragile Goddess, 2002, Fabric, 31.7 x 12.7 x 15.2 cm, Private Collection; © Easton Foundation / ARS, New York, NY Courtesy of Barbara Gross Galerie

(M)other of All Living

Commentary by Holly Morse

Pregnant with possibility, Louise Bourgeois’s Fragile Goddess is a striking sculpture that resonates with a long history of visualizing the fertile female body. Yet, the phallic form at the top of the torso also suggests a blurring of gender identities, allowing the artist to question concepts of masculinity, femininity, sexuality, and power. For Bourgeois, the mother’s body was the source of both triumph and trauma. While the mother was, according to Bourgeois, integral to the human psyche, she was also often displaced and dominated by the father. Consequently, the mother represented in Fragile Goddess is a source of power, but also a site of repression.

This liminal representation of motherhood is found in Genesis 3:16 and 3:20. Woman is condemned to suffer in childbearing, but she is also praised as the ‘mother of all living’. When Adam names the woman in Genesis 3:20 he chooses the name chavvah or ‘Eve’, which probably means something like ‘life-giver’. This name, and the epithet that accompanies it, stand in stark contrast with the preceding punishment of v.16.

Where does this celebration of maternal power come from?

One possibility is that the language used by the Bible about its first woman draws on language used of the 'fragile goddesses' of the ancient Near East. Such goddesses (Eve’s ancient neighbours) were often responsible for earthly fertility and life. One Canaanite goddess in particular shared a similar epithet to Eve, albeit even more celebratory: Asherah was recognized as mother of the pantheon, the ‘mother of the gods’.

Perhaps, then, in the figure of chavvah, we have evidence of the Bible’s efforts to diminish divine feminine power by attributing the impressive title of ‘mother of all living’ to a human female whose maternal body had already been shown to be under the control of God.

References

Bernadac, Marie-Laure. 1995. Louise Bourgeois (Paris: Flammarion)

Wallace, Howard N. 1985. The Eden Narrative, Harvard Semitic Monographs, 32 (Atlanta: Scholars Press)

Wyatt, N. 1999. ‘Eve’, in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd edn, ed. by Karel van der Toorn, Pieter W. van der Horst, and Bob Becking (Leiden: Brill), pp. 316–17

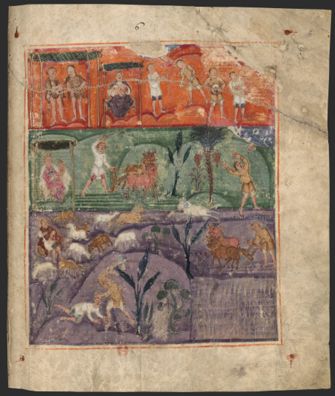

Unknown artist

Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel (Genesis 4), from the Ashburnham Pentateuch (Tours Pentateuch; Codex Turonensis), Late 6th century, Illuminated manuscript, 375 x 310 mm, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; MS nouv. acq. lat. 2334, fol. 6r, Bibliothèque Nationale de France ark: / 12148 / btv1b53019392c

Trouble out of Paradise

Commentary by Holly Morse

‘I have created a man with the Lord’. So says Eve with the conception of her first child.

Or at least, that’s one way we can translate the Hebrew text of Genesis 4:1. In this verse, Eve claims considerable creative power and places herself alongside God in the making of new life. But pride comes before a fall. The man Eve has created is Cain, the child who will go on to murder her second son, Abel.

This detail has been lost in translation for many interpreters of Eve’s experience of motherhood in Genesis 4. For others, the influence she as a mother had over the moral character of her children, and thus subsequent generations of humanity, remained a concern.

In these vividly coloured panels from the Ashburnham Pentateuch we encounter domestic scenes the artist has imagined in the lives of the Bible’s first couple. Interestingly, Eve is represented twice, on both occasions seated beneath a bower, with a child in her lap. The green register includes some Latin text incorporated into the image which makes it clear that here Eve has her son Cain with her, suggesting that perhaps the damaged scene in the orange register would have originally depicted the first mother with Abel.

Further details from within the image support this reading—particularly noticeable is the difference in dress between the two scenes. In the lower image of Eve with Cain, she is clothed in ornate garments by comparison with the more sombre outfit above. This has led some to wonder whether the artist has here judged Eve against the standard of motherhood found in 1 Timothy 2:12, where women are apparently exhorted to be modest mothers if they are to achieve salvation. So, Eve the mother of Cain the murderous son is presented as materialistic and vain in her rich attire, while Eve the mother of Abel the innocent victim appears more subdued and humble. Perhaps, then, this artist held Eve responsible not only for the first sin in the Garden, but also for the sin that was waiting at the door for Cain.

References

Bokovoy, David E. 2013. ‘Did Eve Acquire, Create, or Procreate with Yahweh? A Grammatical and Contextual Reassessment Of qnh in Genesis 4:1’, Vetus Testamentum, 63.1: 19–35

Pardes, Ilana. 1992. Countertraditions in the Bible: A Feminist Approach (Cambridge: Harvard University)

Verkerk, Dorothy. 2004. Early Medieval Bible Illumination and the Ashburnham Pentateuch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Damien Hirst :

Mother and Child (Divided)–Installed at Tate Modern, 2012, Exhibition Copy 2007 (original 1993)–Installed at Tate Modern, 2012 , Glass, painted stainless steel, silicone, acrylic, monofilament, stainless steel, cow, calf and formaldehyde solution

Louise Bourgeois :

Fragile Goddess, 2002 , Fabric

Unknown artist :

Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel (Genesis 4), from the Ashburnham Pentateuch (Tours Pentateuch; Codex Turonensis), Late 6th century , Illuminated manuscript

Eve-ry Woman

Comparative commentary by Holly Morse

Eve’s story has frequently been seen as a tale of temptation and transgression in which she, the Bible’s first woman, takes the lead role. When we picture Eve, it is hard to avoid an image of naked female flesh, serpentine sinews, and the allure of an apple—a composite composition of hundreds of famous drawings, paintings, and sculptures made in response to Genesis 2–4.

But, this popular image of Eden and its inhabitants does a disservice to the complexities of the Garden story, which is rife with ambiguities and tensions.

After all, as much as the story is about death and disobedience, it is also about life. While humanity is ultimately cut off from the Tree of Life at the conclusion of Genesis 3, it will live on and populate the earth. The life Eve and Adam are left with after eating the Fruit of the Knowledge of Good and Bad might be one of hardship and struggle, but death is avoided. For now.

Genesis 2–4 is a story concerned with explaining the bittersweet character of the human condition and humanity’s complex relationship with God and with nature. This is powerfully represented in the strands of the text that represent Eve’s motherhood. Eve embodies the status of all subsequent humans—she is lower than God, yet above the beasts of the field—caught somewhere between divinity and animality.

In certain respects Eve comes remarkably close to God. Her exceptional role as ‘mother of all living’ (Genesis 3:20) and her boastful claim to have ‘created a man with the Lord’ (Genesis 4:1 own translation) combine to create a sense of monumental maternity, echoes of which are detected in Louise Bourgeois’s Fragile Goddess. Eve, in some senses, forms part of a mythic memory in which women across cultures and time have been idolized for their maternal energy.

Yet, in the very same text of Genesis Eve’s fertile body is also marked as a site of struggle and suffering. Humanity should not, Genesis tells us, become too much like God (Genesis 3:22), and so Eve’s potential for power must have limitations. In this she is closer to her animal companions in the garden, the very animals used by Damien Hirst to create his Mother and Child (Divided). She, like them, might be able to produce life, but she too is unable to control death.

Hirst’s choice of cow and calf to represent his mother and child heightens this sense of maternal liminality: while for the viewer the cow is synonymous with life-giving milk, in order to sustain the production of cows’ milk for human consumption, the dairy industry slaughters countless calves daily. The immediate sense of powerlessness represented in Hirst’s bisected mother and calf strongly echoes the powerlessness Eve has over her own mortal body and those of her children. She may be the first mother of all humanity, but this does not allow her to escape the tragedies of parenthood.

As her sons fall victim to violence in Genesis 4, and the tension between humanity and God deepens, Eve continues to play a key role in the unfolding drama of human nature. For some later interpreters of the text, such as the artists of the Ashburnham Pentateuch, Eve’s character, both positive and negative, comes to be imprinted upon her sons and helps to explain their different natures. The prideful potential of the first woman, perhaps revealed when she celebrates Cain’s birth in Genesis 4:1, might be taken as a sign of her responsibility for the sinful side of Cain. Yet, the Ashburnham Pentateuch also reminds us that Eve gave birth to the innocent Abel.

Eve is neither the embodiment of womanly failure, nor the paradigm of female perfection in Genesis 2–4. She is a human figure who grows, learns, suffers, and survives, all the while negotiating with God.

By viewing the Bible’s first woman through this more complex lens of maternal imagery, it is possible to re-evaluate millennia of damaging traditions. In particular, by taking a closer look at the story of Eve, we are encouraged to challenge the popular Christian tradition of Eve as sexualized sinner and Mary as pure, sorrowful mother. Works of art like the ones in this exhibition open up a space of encounter between these two women, as powerful creators and as mourning mothers of innocent sons. They allow us to read the text of Genesis 2, 3, and 4 in a fresh light. They allow us to see Eve anew.

Commentaries by Holly Morse