Luke 8:1–3

Mary Magdalene: From Demons to Discipleship

Frans Francken II

The Penitent Mary Magdalene visited by the Seven Deadly Sins, c.1607–10, Oil on panel, Private Collection; Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Mary Magdalene’s Demons

Commentary by Siobhán Jolley

In Frans Francken the Younger’s striking work, Mary Magdalene recoils from seven demonic creatures that are approaching her from the darkness. The Magdalene is recognizable by her long, loose red hair and hallmark jar of ointment, a symbol stemming both from her role as myrrh bearer after the death of Jesus and her conflation with the anointing woman from Luke 7.

Francken’s religious works are often overtly Catholic in tone, so it is not surprising that he has chosen to depict her demons (from Luke 8:2 and Mark 16:9) as the seven deadly sins, after Gregory I’s pronouncement in Homily 33. They are ambiguous hybrids, clearly bearing the influence of Hieronymus Bosch. Though they surround her and the Magdalene is afraid, they seem unable to reach her.

Francken’s work draws upon other popular Counter-Reformation depictions of the penitent Magdalene in the wilderness, which took inspiration from the Golden Legend’s account of the Magdalene’s hermitic later years. These works often present her, as here, isolated in the wilderness, somewhat unkempt, accompanied by a memento mori (the skull that serves as a reminder of mortality), a prayer book or Bible, and a crucifix.

Where the typical penitent Magdalene might meditate on the crucifix and Christ’s suffering, Francken’s brandishes it almost as a weapon, whilst folding her body around it. Just as other works show the Magdalene wrapped around the foot of the actual cross, this is a visual reminder that it is proximity to Christ that protects her. The divine light in the top left corner adds to the light of her halo, while the demons lurk in darkness.

As Luke suggests, these demons no longer have control over her. Yet Francken’s work offers a stark reminder that keeping them at bay requires ongoing work.

References

Gregory the Great. 1990. Forty Gospel Homilies (Cistercian Publications: Kalamazoo, MI)

Mary Beth Edelson

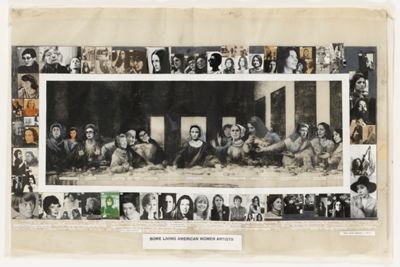

Some Living American Women Artists, 1972, Cut-and-pasted gelatin silver prints with crayon and transfer type on printed paper with typewriting on cut-and-taped paper, 718 x 1092 mm, The Museum of Modern Art; Purchased with funds provided by Agnes Gund, and gift of John Berggruen (by exchange), 4.2010, ©️ Courtesy the Estate of Mary Beth Edelson and David Lewis; Digital image ©️ The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

A Discipleship of Equals?

Commentary by Siobhán Jolley

In Some Living American Women Artists, Mary Beth Edelson gives us an overt visualization of what it might mean to consider the women of Luke 8:1–3 as disciples. In this collage, she takes an iconic artwork, Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper (c.1495–98), a widely recognized depiction of Jesus and his male followers, and subverts our expectations by presenting a group of women. She is, in her own words, ‘spoofing the patriarchy for cutting women out of positions of power and authority’ (Edelson 2002: 32e).

Thirteen women artists take the place of Jesus and the Twelve at the Last Supper (with the ‘mother of American modernism’ Georgia O’Keeffe in Jesus’s central position). Sixty-eight others are depicted in the margin. Alma Thomas (a renowned colourist who began her career as a painter after retiring from school teaching) sits where Leonardo placed Judas but is exonerated from any association with his role by an obliteration of the coin purse in the original. Sculptor, painter, printmaker, and sometime-filmmaker Nancy Graves takes the place of Leonardo’s feminized John, a character sometimes popularly speculated to be a Magdalene! Art, like Christianity, has been dominated by patriarchy. Edelson presents an alternative reality.

The passage in Luke has the power to invite similar introspection and explore what we imagine female discipleship to be. These verses reinforce the fact that women were centrally present in Jesus’s ministry, despite the focus on the Twelve evident in both the Gospels and later Christian tradition. We know from Luke’s own account that there were more than twelve disciples (see, e.g. the sending out of the 72 in Luke 10:1–23). So, what did the ‘ministry’ or diēkonoun of these women entail?

For scholars such as Ben Witherington III (1989), theirs is a ministry of domestic tasks such as food preparation. Others, such as David Sim (1989), reject the implication that the women continued in gender-normative roles. Edelson offers a revisioning that affirms the latter, presenting us with a discipleship of equals where women have a seat at the table—metaphorically and literally—in Christianity.

References

Edelson, Mary Beth. 2002. The Art of Mary Beth Edelson (Seven Cycles: New York)

Witherington III, Ben. 1984. Women in the Ministry of Jesus: A Study of Jesus' Attitudes to Women and Their Roles as Reflected in His Earthly Life (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge)

Sim, David C. 1989. ‘The Women Followers of Jesus: The Implications of Luke 8:1-3’, The Heythrop Journal, 30: 51–62

Janet McKenzie

Companion: Mary Magdalene with Joanna and Susanna, (The Succession of Mary Magdalene) Triptych, First Panel, 2008, Painting, Collection of Catholic Theological Union, Chicago; ©️ Janet McKenzie

Women Who Supported Jesus

Commentary by Siobhán Jolley

Janet McKenzie’s triptych The Succession of Mary Magdalene tells the story of Mary Magdalene from Companion, through The One Sent by Jesus, to Apostle to the Apostles. In this first panel, Companion, she is depicted as we meet her in Luke 8, alongside Susanna and Joanna. Her spiritual growth and development across the three panels is emphasized by her youthful presentation here. She stands centrally, with her eyes closed, having retreated contemplatively within herself; in the latter two panels, she looks directly out at the viewer.

Cloaked in a regal purple, the Magdalene holds a sheaf of wheat, symbolic of the critical role she will play in the resurrection. Susanna, to the left, is recognizable by the distinctive petals of the flower she holds; her name derives from the Arabic sawsan, meaning ‘lily’. Joanna, to the right, holds a cross and is dressed in brown. This garb and attribute might invite us to think of John the Baptist, beheaded at the request of Herod Antipas, the man who employed her husband (Luke 9:9; Mark 6:17–29; Matthew 14:6–12).

We know from Luke 8:3 that these were women ‘of means’ who played a key role in supporting Jesus’s ministry. The artist has described them as ‘a powerful trinity of gifts’. (MMACC 2020). The wheat reminds us that, as first witness to the resurrection, the Magdalene will go on to be more than a financier of the one she follows. Nonetheless, we should not forget the other women either. Richard Bauckham (2002: 165–185), for example, has argued that Joanna goes on to become the apostle Junia (Romans 16:7) and Luke includes her at the tomb alongside the Magdalene (24:10).

McKenzie’s powerful portrayal assures viewers that these women are no longer afflicted by ‘evil spirits and infirmities’ (Luke 8:2) and anchors them at the heart of Jesus’s ministry.

References

Bauckham, Richard. 2002. Gospel Women: Studies of the Named Women in the Gospels (London: Bloomsbury)

MMACC: Mary Magdalene Apostle Catholic Community. 2020. ‘15th Anniversary Year: 2005–20 Feast of Mary Magdalene the Apostle’, available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.cloversites.com/c4/c426c66a-3e96-4114-a2c2-5e43b22073e1/documents/2020-07-26-FeastofMM-worshipaid.pdf [accessed 23 February 2023]

Frans Francken II :

The Penitent Mary Magdalene visited by the Seven Deadly Sins, c.1607–10 , Oil on panel

Mary Beth Edelson :

Some Living American Women Artists, 1972 , Cut-and-pasted gelatin silver prints with crayon and transfer type on printed paper with typewriting on cut-and-taped paper

Janet McKenzie :

Companion: Mary Magdalene with Joanna and Susanna, (The Succession of Mary Magdalene) Triptych, First Panel, 2008 , Painting

There’s Something About Mary

Comparative commentary by Siobhán Jolley

There’s something about Mary Magdalene. Yet, despite her enduring appeal, we find surprisingly little information in the New Testament to flesh out the character who has captured the attention of scholars, believers, and creatives for centuries.

So much of what we think we know is attributable to Magdalene myth, compiled from a number of different sources. As a result of his Homily 33, Pope Gregory the Great is held egregiously responsible for two major misconceptions—namely that Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, and the anointing woman in Luke 7 are one and the same, and that she was a sexual sinner. Though the woman in Luke 7 is described only as hamartolos (‘a sinner’; v.37), which does not in itself suggest anything sexual, the story has been commonly read as alluding to the woman as a sex worker. Gregory’s papal exposition set an authoritative precedent for this interpretation and the Magdalene’s link to sexual sin became, tenuously, anchored in scripture.

So, what do the Gospels actually tell us about Mary Magdalene? Unlike the other Gospels, Luke introduces Mary Magdalene during his account of Jesus’s ministry. In Matthew, Mark, and John, though we are informed that she was present sooner, her first narrative introduction is during Jesus’s Passion (in Matthew 27:56; Mark 15:40; John 19:25). In these scenes, she plays a vital and critical role as myrrh-bearer and first witness to Jesus’s resurrection. At the opening of Luke 8, though, the reader is offered some tantalizing detail, almost in passing, about her role in the early Jesus community and her life before that.

Mary is introduced as part of a group of women who have been ‘cured of evil spirits and infirmities’ (Luke 8:2) as one from whom ‘seven demons’ (Luke 8:1) had been cast out (paralleled in Mark 16:8). There is no qualifying description of what this term means, though the tendency to read demonic possession as directly correlating with mental illness should be pursued with caution. In the aforementioned Homily 33, Gregory suggests the answer is obvious, asking, ‘And what did these seven devils signify, if not all the vices?’ (1990: 269). Given the symbolism of seven as a sign of completeness, it is not too much of an interpretive leap to assume that the seven demons are supposed to indicate something all-consuming—i.e. that she was totally sinful or totally ill. In fact, though, Luke only confirms that this was in her past.

Now, she is named at the head of Luke’s list of women disciples, alongside Susanna and Joanna, the wife of Herod Antipas’s steward Chuza. This description of Joanna gives us some indication of the socio-economic status of these women that is further corroborated by Luke’s affirmation that these women were helping to support the ministry ‘out of their own resources’ (Luke 8:3). Jesus and his followers were itinerant, leaving work and family behind, and lived from a common purse (John 13:29). It seems clear that these women were, to all intents and purposes, funding Jesus’s ministry. More than this, they were ‘ministering’ too (Luke 8:3). The nature of their diēkonoun has been a source of great scholarly dispute, but it is evident that they had a practical role to play also.

These tiny details arguably generate more questions than answers, but they are questions that, with the help of the works in this exhibition, can invite us to think more deeply about Mary Magdalene and trouble our preconceptions. With Frans Francken the Younger we can ask, ‘What does it mean for Mary to have been possessed by seven demons?’. With Janet McKenzie we can consider, ‘How did the Magdalene and other women enable the ministry of the early Jesus community?’. With Mary Beth Edelson we can wonder, ‘What does it look like to conceive of women as close disciples of Jesus?’. As with Luke’s passing mention, this exhibition invites you to think creatively about the things Scripture does not tell us and to reflect deeply on the things that it does.

References

Gregory the Great. 1990. Forty Gospel Homilies (Cistercian Publications: Kalamazoo, MI)

Commentaries by Siobhán Jolley