Matthew 13:1–23; Mark 4:1–20; Luke 8:4–15

The Parable of the Sower

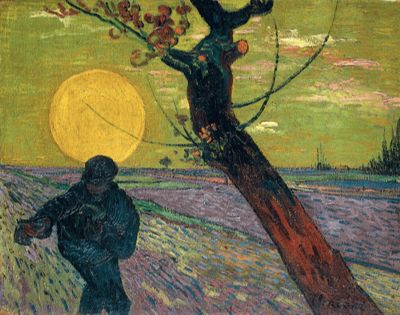

Vincent van Gogh

The Sower, 1888, Oil on canvas, 73 x 92 cm, Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection Zurich; 49, Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

There Went Out A Sower To Sow

Commentary by Michael Banner

Vincent van Gogh was obsessed with the image of the sower, returning to it time and again. He also greatly revered Jean-François Millet’s celebrated treatments of the subject. However, while Millet captured something of the grandeur of the very act of sowing, and indeed of its sacred quality, Van Gogh thought he could make something else and more of the theme, while finding it hard to achieve what he aimed at (Letter 629).

This work from late November 1888, trialled in a smaller canvas painted shortly before, owes much to Van Gogh’s engagement with Japanese prints. He judged it a success. It was, he said, ‘a canvas that makes a picture’ (Letter 723), and contrary to his normal practice, he signed it in the lower right hand corner.

In the foreground a deeply shadowed sower in darkest blue works under a vivid yellow-green sky with pink clouds and a large lemon sun, over a violet earth. He has none of the confidence, almost swagger, of Millet’s figure, and yet the intense, incandescent colours are meant to communicate the intensity of the moment, as the sower, with the sun forming a halo behind his head, bends to his holy task. From his right hand the sower broadcasts seed on the rough (heavily impastoed) ground, and approaches a tree which, bending and twisting like the sower, dramatically divides the canvas on the diagonal.

The tree guides our eye into the picture, providing scale and depth, and also some visual relief from the wearying extent of ground over which the sower has to tread, reaching away to the long and low horizon. More importantly, however, the tree speaks of the aching mix of pathos and consolation which Van Gogh found in this motif. Just as the tree sharply divides the canvas, so the seed will fall into either good or bad soil, to live and bear fruit, or to die.

The tree is heavily pollarded, and at certain times of year, might itself seem dead, like the seed. Yet from its wounds fresh blossom springs, holding over the sower’s lowered head a sign of promise; hope and joy even as the light of the setting sun fades.

References

Van Gogh, Vincent. 2009. The Letters, vol. 4, ed. by Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker (London: Thames and Hudson)

Jan Brueghel the Elder

Seaport with the Sermon of Christ (Harbour Scene with Christ Preaching), 1598, Oil on wood, 79.3 x 118.6 cm, Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich; 187, bpk Bildagentur / Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen, Munich, Germany / Hui Jin / Art Resource, NY

Hearken!

Commentary by Michael Banner

All of the Synoptic Gospels record Christ teaching from a boat on just a single occasion. Mark and Matthew specify that what he teaches on that occasion is the parable of the sower (in Luke, the parable is told later; 8:4–18).

A visual representation cannot very well indicate the content of Christ’s teaching. Nonetheless the scene depicted by Jan Brueghel the Elder is effective in echoing the story of the parable.

We look down towards the harbour from a high vantage point yielding a vast panoramic perspective that reaches to far distant mountains on the horizon. The colours of the picture work to suggest depth, receding from strongly defined forms in dark browns and greens in the foreground, through to fainter contours executed in lighter greens and blue. Characteristically, Brueghel produces not so much a landscape as a dramatic and mysterious ‘worldscape’. This is a monumental vista, taking in entire regions in a way no human eye can.

These worldscapes allow, however, not only a panorama of the natural terrain, but also of the human activity it contains.

Brueghel’s chosen viewpoint enables him to show both Christ preaching from a boat and the burden of that teaching. On the one hand we can make out Christ (just visible on the boat at centre) addressing a considerable crowd, pressing to the very shore-line to hear him. The crowd’s eagerness should not surprise us. In the previous chapter of Mark (3:9), the very reason Christ had asked the disciples to find a boat was just to avoid the crush of those flocking to him. But his parable does not only tell of his word being laid out before the world, as the world is laid out to view in the painting. Nor only of its being heard and taken up. It also tells of its failing to grow and bear fruit. Satan, persecution, and ‘the cares of this world’ (Mark 4:15–19) prevent the seed from coming to harvest.

Brueghel portrayed fish markets like the one in this panel on several occasions. Here, the artist sets Christ’s preaching by the coast, adjacent to the absorbing bustle of just such a market. An eager crowd ‘hears the word’, to be sure; but from a wider perspective, Christ is small and difficult to pick out and his words must compete with all that busyness.

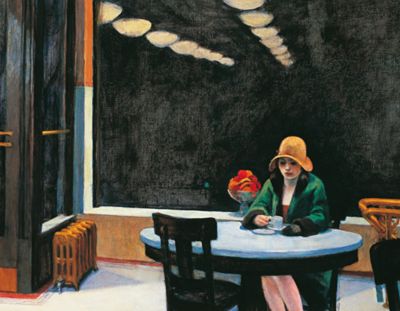

Edward Hopper

Automat, 1927, Oil on canvas, 71.4 x 88.9 cm, Des Moines Art Center, Iowa; 1958.2, © DeA Picture Library / Art Resource, NY

And It Yielded No Fruit

Commentary by Michael Banner

In many of Edward Hopper’s paintings it is as if a curtain has gone up at the opening of a play. The scene is heavy with a certain tense silence, which in a play would be explained and perhaps resolved, but in a painting is destined to remain a mystery, like a parable, inviting interpretation.

The setting, so the title tells us, is an automat. Historically the word named a vending machine, or, as here, a restaurant or cafe in which food was obtained from such machines. Chains of automats flourished in the first half of the twentieth century and were especially popular in New York where Hopper worked. In the picture a well-dressed and attractive young woman sits alone at a table in such an establishment, dressed against the cold with fur trimmed coat and gloves. A glove remains on her hand, as if she feels chilled even indoors. She has eaten whatever modest item of food was on the small plate before her and finishes her drink which, with that radiator by the door, provides some comfort from the cold.

Reflections of the somewhat harsh restaurant lights are prominent above her head. Below them she is lost in her own inward reflections. Her unhappy demeanour suggests that her reflections take her nowhere very far, just as those above her lead only to the utter darkness outside, which ominously reveals no hint of light or life beyond her confines. Mysteriously, while she reflects, she is not herself reflected—the pane of glass which registers the lights does not register her. It is as if she is, to all intents and purposes, invisible.

A colourful bowl sits rather incongruously in the cafe window behind her. Richly symbolic, fruit may suggest temptation, or in the rather desolate automat where one must serve oneself, it may point out temptation’s utter absence. In Christ’s parable, fruit is what is born of seed which falls in good soil, and since the seed is the word, where there is no fruit, the word itself has failed and there is, presumably, only silence. In Hopper’s picture silence is overwhelmingly present.

Vincent van Gogh :

The Sower, 1888 , Oil on canvas

Jan Brueghel the Elder :

Seaport with the Sermon of Christ (Harbour Scene with Christ Preaching), 1598 , Oil on wood

Edward Hopper :

Automat, 1927 , Oil on canvas

The Fate of the Seed

Comparative commentary by Michael Banner

At some time in humankind’s childhood, the sowing of seed allowed agrarian societies to displace hunter–gatherer communities. The seed’s fruitfulness, yielding thirty, sixty, or (rather more rarely) a hundred times what is sown, made a transition possible. Yet that switch was fateful, for once land was settled and farmed, holding it, and holding on to it, became a source of contention, so that the sociality which agrarianism facilitated was at the same time blighted by conflict and violence.

It is striking that in Mark’s Gospel Christ’s first extended body of teaching is a parable about that revolutionary figure at the dawn of human history: a sower. There is also something striking and ironic about the setting for Christ’s teaching of the parable. He is obliged by the press of the crowds to take to a boat, only to deliver a parable which reflects on the failure of his word, the seed, to find a proper hearing and so bear fruit.

In Jan Brueghel the Elder’s painting, Jesus’s call to hear and understand, his ‘Hearken!’, is ignored by those in the busy fish market taking place on the shore line. Laid out in baskets and on the ground is a great variety of fishes, reflecting the variety of people who frequent the market (merchants, stallholders, children, beggars, finely dressed browsers and more serious shoppers), whom Christ, the fisher of men, seeks to draw to himself. At the moment the crowd of those listening outweighs the smaller crowd at the market. But as the parable predicts, some will drift away as the market and the wider world which it represents (and which Brueghel lays out to view with his panoramic perspective), will variously deter, divert, and distract them. Thus the word which has been heard will be prevented from bearing fruit

The parable tells of the fate of the seed, but does not spell out what its fruitfulness symbolizes. What is the great harvest at which Christ the sower aims?

Jesus’s first words in Mark’s Gospel speak of the coming of the kingdom, or kingship, of God (Mark 1:14). Prompted by the word, the world may repent—and under God’s rule, renounce the conflict and violence to which the sowing of seed led and which begins in Genesis 4, when Cain (‘tiller of the ground’) murdered his brother Abel (‘keeper of sheep’).

In the regular work of a perfectly regular sower, Vincent van Gogh found grandeur and poignancy, for the annual sowing of seed is a labour of faith promising renewal and new life. If we envision Jesus as the sower, and his word as the seed, it deepens this poignancy, since Christ the sower laboured till the end of the day, when he himself would be laid dead in the ground. The utter sadness of his rejection lies, however, not in mere personal failure, so to say, but in the fruitlessness of the ground which will not receive and nurture his word.

The world Edward Hopper paints has something of a parable’s simplicity—inessential elements are stripped away in images which have the clarity (but lack of precise detail) of a childhood memory or a dream, and are as archetypal and mysterious as Van Gogh’s sower. The young woman who sits in the automated restaurant has chosen to serve herself and has thus chosen the environment’s loneliness—but the silence does nothing to lighten the burden of her thoughts. The smallness of her plate suggests she has had rather meagre sustenance, and yet over her shoulder, behind her and out of sight, lies a bounty of tempting fruit. And perhaps she fears, in this rather forlorn place, that fruitfulness does indeed lie behind her.

Brueghel’s great panorama of the harbour in which Christ’s boat is moored, gives his teaching an epic context—it takes place not in a mere landscape, but in a worldscape. To this vast world Christ’s teaching is proclaimed, for the sake of reclaiming it. If the word, so the parable tells us, finds good soil and grows, there will be growth, renewal, and fruitfulness, even as from seemingly dead seed scattered in humble faith on the ground. But where the seed is not received, it does not bear fruit and dies, and there will be only the sterility and barrenness of which a deathly and joyless silence is terrible sign.

Commentaries by Michael Banner