John 20:11–18

Noli Me Tangere

Titian

Noli Me Tangere, c.1514, Oil on canvas, 110.5 x 91.9 cm, The National Gallery, London; Bequeathed by Samuel Rogers, 1856, NG270, © National Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY

Crossing Over

Commentary by Devon Abts

Titian imagines Christ’s post-resurrection meeting with Mary Magdalene, not beside an empty tomb, but in a lush hilltop garden overlooking the Italian countryside. As the sun rises beyond the frame of the painting, the world wakes to new life: the resurrection dawn heralds the reversal of the Fall and Christ’s triumph over death.

The artist thus renders his landscape as the new Eden. The rising sun gently illuminates the top of a building in the distance, and casts a further glow on the leaves of the tree that surges upward through the middle of the painting. Wild grasses spring to life beneath Christ’s feet, and behind Mary a large bush sends untamed, lively branches in every direction. In the distance, lambs graze in a fertile pasture, and beyond, undulating hills peppered with trees stretch to an infinite sea.

This landscape feels breathtakingly real—and, importantly, Christ and Mary are entirely at one with their evocative surroundings. Note again the gently-sloping tree rising behind the central figures. This is a common iconographic feature in many Noli Me Tangere images, used to divide the canvas: the resurrected Christ on one side, the Magdalene on the other. Yet note how, in this image, the line of Mary’s back seems to continue along the curve of the tree, while the arc of Christ’s body blends harmoniously into the slope of the hill in the distance.

In this way, Titian articulates his figures along two intersecting lines: one extending from Christ’s foot, along his body and through the cityscape in the distance, and another from the bent figure of Mary through the top of the tree. Within this compositional structure, Christ and Mary are not divided at all: rather, each trespasses on the other, signifying a kind of intersection between human aspiration and divine grace.

References

Benay, Erin E., and Lisa M. Rafanelli. 2017. Faith, Gender, and the Senses in Italian Renaissance and Baroque Art (London: Routledge)

Drury, John. 1999. Painting the Word (New Haven: Yale University Press)

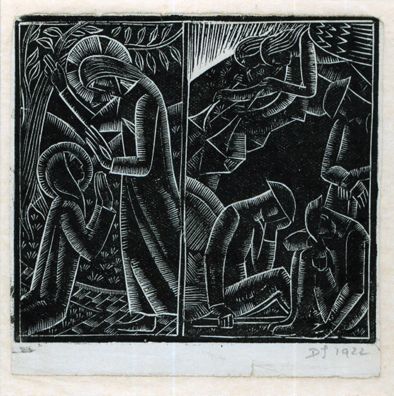

David Jones

Noli Me Tangere/Soldiers at the Tomb, 1922, Engraving, 762 x 889 mm, Private Collection; © Estate of David Jones / Bridgeman Images; Photo: courtesy of JHW Fine Art

An Emblem of Hope

Commentary by Devon Abts

Over the centuries, many artists have paired the Noli Me Tangere with another biblically-inspired scene—namely, soldiers sleeping outside Christ’s tomb. This latter scene is based on Matthew 28:12–15, where the chief priests attempt to cover up the resurrection by bribing the Roman soldiers guarding Christ’s tomb to say that his body was stolen when they fell asleep. Iconographically, these soldiers offer an intriguing foil for the Magdalene: whereas she hears and responds to her Lord’s voice miraculously calling her name, they remain deaf to the sound of angels heralding the resurrection.

David Jones’s image draws upon this traditional iconographic pairing. Here, however, the men keeping watch are not Roman guards keeping watch over Christ’s tomb, but British soldiers fighting in the Great War.

The artist, who was haunted by his own experiences in the trenches, portrays these men with admirable sympathy. Above their heads, the sun is rising over the horizon and angels are sounding trumpets of the resurrection. Yet these exhausted soldiers are too wearied to hear the heavenly music. Facing the empty, nihilistic tomb, these men are as much victims as they are perpetrators: robbed of their agency, the soldiers represent man’s enslavement under the horrifying conditions of war.

All of this is set in contrast to Mary, whose liberation and agency is made possible through her willing ‘enslavement’ to Christ. Kneeling before the risen Lord, she submits herself to his will and purpose. The reward for her faithful obedience is the knowledge of the resurrection.

Importantly, however, this contrast between the Magdalene—who sees clearly—and the guards—blinded by the fog of war—is not meant to chastise the soldiers, but to suggest the possibility of their final redemption. Can they, like Mary, hear the risen Christ’s voice and turn to embrace new life?

A Eucharistic Blessing

Commentary by Devon Abts

David Jones’s 1922 engraving of the Noli Me Tangere—created just a year after his conversion to Roman Catholicism—resonates with sacramental and liturgical overtones. Christ stands over Mary in an unmistakably priestly posture, with his right hand raised in a gesture of blessing; at the same time, his left hand is held up both to prevent her from touching him, and to show her the scars from his suffering. Mary, meanwhile, kneels before her Lord as if at an altar rail, with her hands raised to receive the gift of blessing that Christ offers to her. Her eyes are fixed on his wounds with unyielding devotion, calling to mind the Catholic liturgy of Benediction (in which the Blessed Sacrament is brought forth for adoration). It is as if the living and resurrected Christ is the Eucharist, a real presence whose miraculous resurrection triumphs over death.

As he prepares for his impending physical departure from the world, Jesus shows himself to Mary in such a way as to remind her that he will remain with the faithful in and through the life of the Church.

Jones foreshadows Christ’s imminent withdrawal from this world—and from Mary in particular—by imagining their encounter at a literal point of juncture: the Magdalene kneels on a small patch of grass at a fork in the road, implying that Christ will soon depart in one direction, and that she will set off in the other. Yet this moment in the garden reminds us she will be sent with Christ’s blessing and commission to be his servant in the world after he has ascended. Perhaps the artist wishes to remind the beholder of this work that she, too, is blessed and commissioned by God through her participation in the liturgy.

Fra Angelico

Noli Me Tangere; Christ meets Mary Magdalen in the Garden, Cell 1, 1438, Fresco, 166 x 125 cm, Museo di San Marco, Florence; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

A Message of Mission

Commentary by Devon Abts

Fra Angelico’s ethereal frescoes in Florence’s Dominican Convent of San Marco were created not as decoration, but as aids to contemplation and devotion. His Noli Me Tangere is one of several frescoes adorning the walls of the private dormitory cells where the friars of the convent slept and prayed in solitude. Depicting scenes from the life of Christ, these images would have provided each cell’s inhabitant with both a source of contemplation, and with a reminder of his vocational duties.

To the friars living in this particular cell, Fra Angelico’s Noli Me Tangere would have served as a reminder of his anointed duty to preach the message of salvation to the world.

Christ’s charge to Mary Magdalene in John 20:17 is to deliver the news of the resurrection to the disciples. This would have been a particularly worthy subject of contemplation to the followers of Dominic, who founded his Order to spread the message of salvation through preaching. As the Apostle to the Apostles, Mary is the first to bring this message to the world.

Fra Angelico’s Noli Me Tangere thus presents Mary as witness to the resurrection who offers herself to Christ in obedience and love. His scene captures the moment of recognition, when Mary realizes that the man who calls her by name is not a gardener, but the living Christ. Humbling herself before him, Mary gazes on his face with absolute serenity. She reaches out to touch the miraculous body of her Lord. Yet notice how Mary’s arms are not so much extending forward as they are opening outward.

Mary is offering herself to Christ’s service. And Christ, in turn, speaks to Mary, anointing the woman who had come seeking to anoint him: henceforth, her task will be to openly deliver the good news of the resurrection.

References

Gregory of Nyssa, Against Eunomius VII

Benay, Erin E., and Lisa M. Rafanelli. 2017. Faith, Gender, and the Senses in Italian Renaissance and Baroque Art (London: Routledge)

Making All Things New

Commentary by Devon Abts

In this contemplative image depicting Mary’s encounter with Christ in John 20, Fra Angelico captures the miraculous transformation of the world on the morning of Christ’s resurrection. The scene unfolds at dawn in a vibrant walled garden bursting with life. Scattered between delicate grasses and shrubs are tiny red flowers painted the same colour as the visible wounds on Christ’s hands and feet, reminding the viewer of the sacrifice that makes all things new. The dense forest beyond suggests that this renewal cannot be contained, but spills over into the entire world.

Significantly, Mary herself is caught up in this transformation. With her back to the empty tomb, she is portrayed in a moment of conversion. It is as though she is stepping out of the cave in Plato’s Republic, turning from the shadows of sin toward the resurrection light. Fra Angelico underscores this theme by evoking the idea—common in medieval Europe—that Mary Magdalene is the ‘sinful woman’ who anointed Jesus’ feet with her tears in Luke 7:36–50. Just as Luke’s sinful woman repented through tears, Fra Angelico’s Magdalene is painted with a face flushed from weeping as she turns toward her Saviour.

Even Christ is depicted in an in-between state: hovering lightly over the ground, he already seems to be ascending. This artistic detail evokes the traditional patristic understanding that Christ’s appearance to Mary on the morning of the resurrection heralds the transformation of humanity’s relationship to God. Mary must let go of the earthly Christ so that she may attain the knowledge of the heavenly Christ, who ascends to the Father in glory.

To San Marco’s mendicant friars, the fresco’s message would be clear: being transformed by God begins with renouncing earthly desires, including the desire to hold onto or possess Christ as some sort of material object.

References

Gregory of Nyssa, Against Eunomius VII

Benay, Erin E., and Lisa M. Rafanelli. 2017. Faith, Gender, and the Senses in Italian Renaissance and Baroque Art (London: Routledge)

Titian :

Noli Me Tangere, c.1514 , Oil on canvas

David Jones :

Noli Me Tangere/Soldiers at the Tomb, 1922 , Engraving

Fra Angelico :

Noli Me Tangere; Christ meets Mary Magdalen in the Garden, Cell 1, 1438 , Fresco

Do Not Hold onto Me

Comparative commentary by Devon Abts

In their respective Noli Me Tangere images, Fra Angelico, Titian, and David Jones each counterbalance Christ’s seemingly harsh words in John 20:17—'Do not hold on to me’ or ‘Do not touch me’—by evoking the love shared between Christ and Mary Magdalene.

Painted on the wall of a Dominican friar’s cell, Fra Angelico’s fifteenth-century fresco was intended as an aid to contemplation and private devotion. Here, the meeting between Christ and Mary takes place in an enclosed garden, called a hortus conclusus (after Song of Solomon 4:12: ‘A locked garden is my sister, my bride’)—a place of innocence, and of intimacy. The resurrected Christ bears a cruciform nimbus, reminding the viewer of his divinity. His luminous body almost seems to hover above the delicate grasses and flowers beneath his feet, as if he is already ascending. Yet his gaze remains fixed on the woman before him in an expression of tenderness and compassion. Kneeling in wonder and reverence, Mary returns Christ’s gaze, showing her still tear-stained face. She is the penitent Magdalene, turning from the empty tomb at the sound of her teacher’s voice. As she reaches out to touch him, he raises his hand in gentle admonition and gives her a new commandment: to deliver the news of his resurrection to others. With great economy of detail, Fra Angelico suggests that the encounter with Christ is too precious and too intimate to be hoarded. For the occupant of this cell, this image would have been a powerful reminder of his own duty to follow Mary’s example by sharing the message of the resurrection in humility and sacrificial love.

This is a striking contrast to Titian’s painting, in which the love between the two figures is given distinctly erotic overtones: here, Christ the ‘gardener’ becomes the masculine seed-sower, and Mary as spice-bearer is an emblem of feminine beauty and desire. Unlike the humble and obedient Mary of Fra Angelico’s fresco, this Mary is caught in a moment of near-transgression: the artist captures her desire to touch Christ’s body through her outstretched hand, which reaches suggestively towards the knot that barely covers Christ’s loins. Meanwhile, the risen Saviour gazes lovingly upon the woman at his feet, and even as he leans away to resist her touch, he stretches himself over her, penetrating the space she occupies with his upper body. To underscore the sensuality of this moment, the artist envisions their meeting in a sumptuous garden, sparing no detail in his evocative depiction of the fertile landscape. In this painting, then, the love between the two central figures is charged with longing, as Mary’s desire to touch Christ’s physical body becomes the unattainable yearning of her innermost being.

Finally, Jones’s engraving also captures an intimacy between Christ and Mary Magdalene, but here, the overtones are sacramental, and a spare simplicity is used to suggest the purity of love between the two figures. Whereas Titian’s Christ wears little more than a cloth draped suggestively around his genitals, in this image Christ is modestly covered from head to foot in resurrection robes. Mary, too, is modestly dressed, wearing a simple dress and full headscarf—a stark contrast to the opulent robes worn by Titian’s Magdalene. Mary’s hands are raised towards Christ’s body, but, like the woman in Fra Angelico’s fresco, she does not seem to be reaching out to touch him; rather, her outward facing palms suggest that she is opening herself to receive Christ’s blessing. There is an unmistakable sense of intimacy between the two figures: as in Titian’s painting, Jones portrays Christ as protectively arching himself over Mary, whom he regards with tenderness and affection. And the tree branch arcs over them like a marriage canopy, binding Christ and Mary together in a shared physical space. Yet the exchange of love here is unmistakably sacramental: Christ’s gift of sacrificial love—represented by the wounds on his hand and side—is received and reciprocated by Mary’s loving gaze.

For each of these artists, the encounter between Christ and Mary Magdalene in John 20 represents a convergence of human and divine love. While Titian’s sensual image affirms the goodness of human longing after the divine, Fra Angelico’s fresco invites the beholder to contemplate and respond to the calling of this love. Finally, Jones suggests to his viewer that this love remains available to all through the sacramental gifts of the Church. In vastly different ways, then, each artist suggests that Christ’s injunction not to touch is an invitation to relationship rather than a reproach against our humanity.

Commentaries by Devon Abts