Luke 7:36–50

Redeeming the ‘Sinful Woman’

William Blake

The Penance of Jane Shore in St Paul’s Church, 1793, Ink, watercolour, and gouache on paper, 245 x 295 mm, Tate; Presented by the executors of W. Graham Robertson through the Art Fund 1949, N05898, © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Performing Penance

Commentary by Maryanne Saunders

The Penance of Jane Shore in St Paul’s Church by William Blake does not refer directly to Luke 7. Rather, Blake’s work depicts the historical event of the public penance of King Edward IV’s mistress Elizabeth ‘Jane’ Shore after the monarch’s death in 1483.

The ‘walk of shame’ demanded of the noble woman Jane Shore after her long romances with the King and other nobility, was ostensibly a punishment for her wantonness and sexual immorality. Others theorized that the spectacle was in fact orchestrated by Edward’s brother, Richard III, in response to allegations that Jane had been passing political messages amongst his enemies.

It is the punishment itself, rather than the crime, that is depicted in this work by Blake, made two centuries after her death and undoubtedly with Early Modern plays based on her life in mind. Jane steps towards the centre of the composition. She is wrapped in a blanket over her kirtel (underdress) and holds a taper in her hand. She is surrounded by a group of soldiers and at right a group of spectators stare at her, perhaps censoriously.

This work is interesting for the manner in which it depicts female penitence and what appears to be the inevitable public humiliation that accompanies it. Jane is half dressed by the standards of Tudor nobility, and—in a way not dissimilar to the Rubens painting elsewhere in this exhibition (albeit with a very different level of agency over the situation)—she is placed at the forefront of the bustling crowd. It is a place of exposure.

Nevertheless, the presence of the soldiers is indicative of Jane’s status, class, and relative safety despite the situation. Although she was subject to taunts and was even imprisoned, she later married, living out the rest of her life in bourgeois comfort.

The viewer may read the scene as one of a powerless woman, forced to humiliate herself in public for the sake of a tyrannical king. Alternatively, we may see a political agent escaping harsher punishment by shielding herself in her gender and class.

Peter Paul Rubens

Feast in the House of Simon the Pharisee, 1618–20, Oil on canvas, 189 x 284.5 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.; Entered the Hermitage in 1779; acquired from the R. Walpole collection, Houghton Hall, England, ГЭ-479, HIP / Art Resource, NY

Supplication or Subjugation?

Commentary by Maryanne Saunders

The left side of Peter Paul Rubens’s composition is crowded with jostling guests, servers, and attendants. Faces, dishes, and fabrics create a maelstrom of bodies and material possessions in stark contrast to the sober black background which frames the figures on the right of the painting. Jesus and his disciples are depicted by the Flemish artist as calm and composed in the face of the disordered rabble opposite them.

Even though the title that has been given to this painting omits any mention of the sinful woman, the swirl of people and the dramatic lighting draw the eye inwards towards the central, lowered figure of the woman by Jesus’s feet. Her porcelain skin and body are emphasized by a low-cut dress and hair pushed back from her face. Her supplication is demonstrated in her posture and proximity to Jesus’s foot as she both applies and seems to smell the anointing oil while kissing Christ’s feet in an act of devotion and tenderness.

Only one disciple appears to look down at the woman, as Jesus and the man we can assume to be Simon the Pharisee—seated opposite him—debate their respective positions on forgiveness (Luke 7:44).

As absorbed in and committed to her task as the woman is, the extent to which the artist has emphasized her submission and sensuality could be interpreted as debasing, even humiliating. Many other examples of artworks illustrating this narrative place the woman not just on the floor out of necessity, but in a near prostrate position, crawling and half-dressed. This example begs the question of whether women’s public shaming is intrinsically tied to their redemption in a way that the redemption of male biblical protagonists is not.

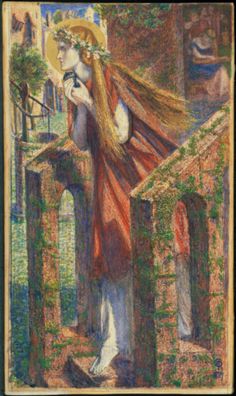

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Mary Magdalene Leaving the House of Feasting , 1857, Watercolour on paper, 356 x 206 mm, Tate; Purchased 1911, N02859, © Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

The Magdalene Moves On

Commentary by Maryanne Saunders

Mary Magdalene Leaving the House of Feasting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti explicitly identifies Mary Magdalene as the ‘sinful’ woman mentioned in Luke 7:37, in a tradition that goes back to Pope Gregory I, and that is still common today (despite the Roman Catholic Church officially distancing itself from this view in 2016).

The figure of the protagonist in the foreground dominates the watercolour, leaving only a small background scene visible at the right of the sheet. The female figure in this secondary scene may well represent Mary a second time, at an earlier point—before her departure from the house of the Pharisee.

The position of her feet and windswept hair indicate she is hurrying from the scene with purpose. Mary’s demeanour is solemn, she clutches her pot of ointment to her chest protectively and appears determined. A halo glows around her head indicating her holiness and perhaps her newfound status as one who has been saved.

The Magdalene was closely associated in Christian tradition with prostitution and extra-marital sex, particularly in the Victorian era where homes for ‘fallen’ women and other charitable endeavours were founded and often dedicated to her to eradicate this ‘problem’ in the lower classes. Rossetti does not, however, depict a wanton or degraded Magdalene so as to make of her a cautionary tale. Instead, the artist has chosen an empowered, renewed, and even inspirational character for his painting.

The story clearly fascinated Rossetti: he went on to depict Mary twice more in Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the Pharisee (1858) and a portrait study in 1859. The overwhelming impression given by this work is one of redemption, forgiveness, and moving on. Mary moves swiftly from her old life and devotedly into the new one she has chosen with Christ. Although depicting a story of contrition, Rossetti appears to celebrate the vulnerability and bravery it takes to repent rather than relishing the spectacle.

William Blake :

The Penance of Jane Shore in St Paul’s Church, 1793 , Ink, watercolour, and gouache on paper

Peter Paul Rubens :

Feast in the House of Simon the Pharisee, 1618–20 , Oil on canvas

Dante Gabriel Rossetti :

Mary Magdalene Leaving the House of Feasting , 1857 , Watercolour on paper

The (Gender) Politics of Penitence

Comparative commentary by Maryanne Saunders

The story of the sinful woman (and her subsequent redemption) is one synonymous with feminine penitence, and all the potential for submission and power this entails. By exploring these three works individually—one illustrating the verse itself, another the aftermath, and one depicting an entirely separate episode of public penitence—we are able to draw parallels between the ways that each artist has presented his protagonist and what gendered assumptions are potentially made by both artists and viewers.

Peter Paul Rubens’s visual interpretation of Luke 7:36–50 in The Feast in the House of Simon the Pharisee is sensual and dramatic, highlighting the vulnerability and sexuality of the sinful woman as she crawls on the floor and submits herself to Jesus. It is arguable that repentance absolutely requires this level of humility. However, it is worth considering whether the woman said to be guilty of sexual misdemeanours is particularly liable to salacious depictions. For example, another penitent sinner is King David, but when he is depicted in art, he is both sympathetic and still noble. In other words, he does not lose his dignity in the process of his redemption.

It would be simplistic to state that all depictions (or, indeed, acts) of female penitence are to be viewed through a lens of degradation and/or patriarchy. Indeed, as we see in William Blake’s rendering of The Penance of Jane Shore in St Paul’s Church the narrative can be much more complicated. Shore is being ostensibly punished for sexual crimes. Her punishment involves humiliation, partial undress, and crowds. However, it is speculated that her punishment was in fact a warning against her political activities: crimes that could have seen her put to death by the King if found guilty. If this is the case, Shore may well have been accepting the ‘lesser’ punishment and enacting penitence in order to ensure her personal safety. Protected from physical violence by the surrounding guards, Shore’s pose in Blake’s interpretation projects an image of a sympathetic, humble, even noble character.

Repentance is not always about weakness; sometimes it can be very powerful as indicated in later events in the Gospel of Luke: ‘Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance’ (Luke 15:7). An intriguing historic example of this comes in the form of the convicted English adulterer and ‘murderess’ Elizabeth Caldwell (d.1603). Caldwell’s repentant writings and letters to her husband, the (intended) victim of her crimes, became widely known after her execution. Even in her lifetime, the prisoner’s ‘spiritual reformation … drew crowds to visit her, “no fewer some days than three hundred persons”’ (Dugdale 1604). Lynn Robson posits that Caldwell’s penitence made her a spiritual authority in her time, a feat rarely, if ever, accomplished by women. Through her writings, she absolves herself of her crimes by reflecting on how her ‘physically weak female body and her morally weak, irrational female soul’ led to her corruption by the men around her—including her neglectful husband and seductive lover. Peter Lake argues that by deferring to the ultimate masculine authority in God, women were able to achieve relative freedom from social and sexual subjugation to masculine authorities (Lake 1987).

It is with this notion of empowerment in mind that we continue to the last image, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Mary Magdalene Leaving the House of Feasting. The sinful woman, here, is not as we have seen her before. In the aftermath of the events within the house, she appears assured and purposeful. Her ointment—a reminder of her penitent act—is clutched close to her chest protectively as if she treasures it.

In this painting, the viewer sees a woman who is at peace, and who has achieved this state herself. The basis of her perceived sins may be rooted in misogyny, but this protagonist—like Elizabeth Caldwell—has harnessed the power available to her in the situation in which she finds herself and has raised her own status in the eyes of the populace and in history through her very public, demonstrable repentance.

What we as viewers may learn from these very different visual approaches to penance is that it is a multi-faceted experience. One person may find the vulnerability of such an act exposing or degrading, while another may find that intrinsic to repentance is the power and promise of a new start.

However, we see it, the Magdalene—at least in her visual legacy—has come to embody both the strength and the weakness of this humanly deep and demanding process.

References

Dugdale, Gilbert. 1604. A True Discourse of the practices of Elizabeth Caldwell (London), STC 4704, sig. B2r

Lake, Peter. 1987. ‘Feminine Piety and Personal Potency: The ‘‘Emancipation’’ of Mrs Jane Ratcliffe’, Seventeenth Century, 22: 143–65

Robson, Lynn. 2008. “‘Now Farewell to the Lawe, too long have I been in thy subjection’: Early Modern Murder, Calvinism, and Female Spiritual Authority’, Literature and Theology, 22.3: 295–312

Scott, Maria. 2005. Re-Presenting 'Jane' Shore: Harlot and Heroine (Aldershot: Ashgate)

Commentaries by Maryanne Saunders