Psalm 145

All Creatures Great and Small

Joris Hoefnagel

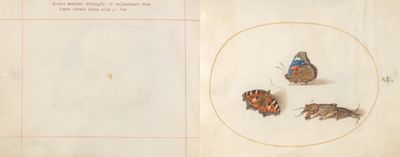

Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate XI, c.1575–80, Watercolour and gouache, with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Gift of Mrs. Lessing J. Rosenwald, 1987.20.5.12, Photo: Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

An Unusual Encounter

Commentary by Marisa Bass

The first book devoted to the representation of insects in the history of art and science might seem an unlikely place to find a quotation from the Scriptures. Yet inscribed on the verso shown here is the ninth verse of Psalm 145:

The Lord is good to all, and his compassion is over all that he has made. (v.9)

This opening belongs to a stunning late sixteenth-century manuscript created by the Netherlandish polymath Joris Hoefnagel. It forms part of his project known as the Four Elements: a visual encyclopaedia of nature’s creatures spread across four volumes, which together contain some three hundred illuminated folios and over one thousand inscriptions. The small scale and oblong format of the manuscripts indicate that they were meant to be held and studied up close. It is precisely this kind of sustained contemplation that Hoefnagel’s insect volume rewards.

On the recto opposite the excerpt from the psalm, a congregation of specimens suggests just how far God’s compassion extends. The two butterflies seem at first to be engaged in conversation. On closer inspection, the disagreement in the shadows that they cast places them realms apart. The red admiral at centre stands in profile within a space of implied depth, while the small tortoiseshell below seems to be resting on the surface of the page. Both are labelled with the number ‘1’ as if to indicate their affinity.

Nonetheless, the distinct spatial worlds they inhabit further compel us to observe the subtle differences in their colour and patterning, which appear all the more marked beside the third and final insect within the frame. How to account for this lumbering little beast with its burrowing claws, pointy snout, and beady eyes? If God is good to all his creatures, then even the inelegant mole cricket exists by divine grace.

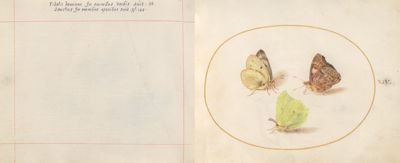

Joris Hoefnagel

Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate XII, c.1575–80, Watercolour and gouache, with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Gift of Mrs. Lessing J. Rosenwald, 1987.20.5.13, Photo: Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

A Double Take

Commentary by Marisa Bass

On the second folio of Joris Hoefnagel’s Four Elements, we find the mole cricket in a rather compromised state. On the first folio, he appeared upright. He now lies inert and overturned on the parchment, his squat limbs and underbelly exposed. Beside him are two butterflies who have taken the place of their counterparts on the preceding folio—dark green fritillaries aptly named for the verdant tint of their hindwings.

Keeping to the same compositional structure, but changing subjects and shifting pose, Hoefnagel animates his insects across successive frames. The manuscript transforms from a collection of studies into a microcosmic world that comes alive at the touch and before one’s eyes.

With the turn of the page, Hoefnagel also continues the exegesis of Psalm 145 which began on the previous verso. The tenth verse of the hymn now appears in the upper register of the verso:

All your works shall give thanks to you, O Lord, and all your faithful shall bless you. (v.10)

We might interpret this line in relation not only to the trio depicted in the adjacent image but also to Hoefnagel’s own endeavour of making the manuscript itself.

The prostrate mole cricket exposes the process that underlay the workings of Hoefnagel’s inquiring hand. Only close study of dead specimens would have allowed him to capture his subjects in such precise detail. But only rarely do his miniatures so explicitly lay bare the labour and virtuosity required to re-enliven a lifeless body on the page.

To study nature in the sixteenth century meant to seek an understanding of the infinite design and astounding diversity implicit in a realm that God created. In this respect, Hoefnagel’s painstaking studies reflect a practice at once empirical and devotional. At every turn, his efforts compelled admiration for the divine artifex from whom he understood all his subjects, and his own artistic talent, to derive.

Joris Hoefnagel

Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate XIV, c.1575–80, Watercolour and gouache, with oval border in gold, on vellum, 14.3 x 18.4 cm, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Gift of Mrs. Lessing J. Rosenwald, 1987.20.5.15, Photo: Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Words and Deeds

Commentary by Marisa Bass

Among the remarkable aspects of Joris Hoefnagel’s insect volume is its attention to a category of living organisms in which Renaissance naturalists had only just begun to take an interest. The first published treatise devoted to insects was not published until after Hoefnagel’s death in 1600.

In creating the other volumes of the Four Elements, Hoefnagel was able to borrow models from existing illustrations of birds, fishes, reptiles, and mammals. But when it came to insects, Hoefnagel had to rely almost exclusively on his own scrutiny of specimens first-hand.

At the same time, the combination of text and image through the manuscript makes clear that Hoefnagel was not pursuing the construction of a clear taxonomy, or engaging with his subjects as would an entomologist today. Nowhere in any of the volumes is there a key identifying the names of the particular species depicted, even despite the occasional numbers that appear alongside them.

The texts that Hoefnagel chose for inclusion in the volumes instead form a commentary of a very different sort. They reflect the lessons that might be derived from the investigation of the natural world, and a conviction that even the tiniest insect that exists has something to teach us.

‘The Lord is faithful in all his words, and gracious in all his deeds’ (v.13) reads the line from Psalm 145 that Hoefnagel selected to accompany the three butterflies arranged within the ovular frame shown here. Their symmetry on the page—as on the pages treated elsewhere in this exhibition—puts the uniqueness of each individual specimen into greater relief. By displaying all three in profile, Hoefnagel allows for observation of the distinctions not just in the colouring but also in the shape of their wings.

Pairing words of divine praise with examples of God’s wondrous deeds, we simultaneously read and see the faithful investment in every living thing that the verse proclaims.

Joris Hoefnagel :

Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate XI, c.1575–80 , Watercolour and gouache, with oval border in gold, on vellum

Joris Hoefnagel :

Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate XII, c.1575–80 , Watercolour and gouache, with oval border in gold, on vellum

Joris Hoefnagel :

Animalia Rationalia et Insecta (Ignis): Plate XIV, c.1575–80 , Watercolour and gouache, with oval border in gold, on vellum

Even the Smallest Things

Comparative commentary by Marisa Bass

Psalm 145 marks a turning point in the biblical book as a whole: it is both the last of the psalms attributed to King David and the first in a final series of hymns that shift from prayer to praise. The verses extol God’s works and compassion while acknowledging the unfathomable nature of their source. His greatness is to be praised, and yet ‘His greatness is unsearchable’ (v.3). The psalm exhorts us to embrace this paradox, to meditate upon it, and to find solace within it.

But to whom is the psalm addressed? Its last line declares that ‘all flesh will bless his holy name’ (v.21). Are all living creatures capable of praising God’s works and the ‘glorious splendour’ (v.5) of the heavenly kingdom?

In his seminal commentary On the Psalms, St Augustine baulked at the notion that non-rational animals could actively participate in the adoration of the divine. Augustine’s solution was simple: consciously or not, every creation of God’s hand reflects his majesty and thereby honours his name. Speaking to his fellow mortals, this doctor of the Church writes:

And here, in this beauty, in this fairness almost unspeakable, here worm and mice and all creeping things of the earth live with you, they live with you in all this beauty. (On the Psalms 145: 12)

Augustine was not alone in querying humankind’s relation to nature’s most minuscule creatures. Ancient writers such as Aristotle and Pliny the Elder had already taken up these questions in investigating the ‘creeping things’ that inhabit the world around us. By the mid-sixteenth century, the inflection of this tradition with a newfound emphasis on empirical observation informed the emergence of natural history as a field of study that engaged European scholars, artists, and collectors alike.

As Renaissance naturalists pursued knowledge of nature’s creatures, they commissioned and compiled images to accompany their written descriptions of various plant and animal species. They also gathered moral wisdom about their subjects from classical, humanist, and scriptural learning, glossing accounts of a given creature’s habits and character as exemplary for humankind.

Joris Hoefnagel’s Four Elements represents a singular response to this development. Like Augustine, Hoefnagel recognized something ineffable in the wondrous beauty and diversity of nature. He applied his creative abilities toward the praise of a divinely created world that he never hoped to understand in full.

His choice of the manuscript medium speaks to a personal engagement with his subjects. The project of Four Elements occupied Hoefnagel for over two decades. The volumes reflect observations made on his extensive travels, his wide reading, and exchanges with fellow scholars and artists. Each verso, inscribed text, gilded border, and meticulously painted miniature index the time and extreme patience that he devoted to his reflections on the natural world.

Although his son Jacob Hoefnagel, who was also an artist, eventually produced a series of prints based on his father’s collection of studies and inscriptions, there is no evidence that the elder Hoefnagel either sought or anticipated a broader audience for his work at the outset.

Over the course of gathering material and producing the miniatures themselves, Hoefnagel’s life was also in a state of almost constant metamorphosis. He began his career as a merchant in the thriving southern Netherlandish metropolis of Antwerp, though even in his youth, he pursued drawing and painting on the side. But when the Revolt of the Netherlands against Spanish imperial rule wrought havoc on his homeland and his family’s commercial prosperity, he fled Antwerp’s inquisitional climate in search of better prospects abroad. There he found refuge in a second career as a court artist. Moving from Munich to Frankfurt and eventually to Vienna, he continued to reinvent himself as he worked for various patrons and negotiated the political and spiritual upheaval of the times.

In Hoefnagel’s persistent return to insects as subjects, and to the hymns of lament and praise in the Book of Psalms, he embraced a faith grounded in the Book of Nature and untethered from the confessional divides that had fomented the war in the Low Countries. Perhaps Hoefnagel saw in nature’s most skilful artificers something more than the manifestation of God’s wondrous works: a model for negotiating his own career of exile and transformation.

References

Bass, Marisa Anne. 2019. Insect Artifice: Nature and Art in the Dutch Revolt (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Hendrix, Lee. 1995. ‘Of Hirsutes and Insects: Joris Hoefnagel and the Art of the Wondrous’, Word & Image 11: 373–90

Neri, Janice. 2011. The Insect and the Image: Visualizing Nature in Early Modern Europe, 1500–1700 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press)

Vignau-Wilberg, Thea. 1994. Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii, 1592: Natur, Dichtung und Wissenschaft in der Kunst um 1600 (Munich: Staatliche Graphische Sammlung)

Commentaries by Marisa Bass