Psalm 147

A Song of Thanksgiving

Unknown artist, England

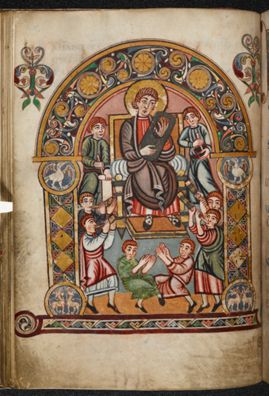

King David and his Musicians from the Vespasian Psalter, 8th century, Manuscript illumination, 240 x 190 mm, The British Library, London; Cotton MS Vespasian A I, fol. 30v, ©️ The British Library Board (Cotton Vespasian A I, f.30v)

Praise is Comely

Commentary by Anna Gannon

This illuminated page comes from the earliest known book from the south of England: the ‘Vespasian Psalter’. It is a majestic Anglo-Saxon Psalter written in a stately script (‘uncial’). It was most probably produced in Canterbury, c.725, using Jerome’s Latin version of the Psalms translated from the Hebrew.

The miniature affords a colourful glimpse into the joyous, action-filled, and noisy court of King David, celebrated author of several psalms. David, haloed and swathed in purple, sits on a plump cushion on his throne, surrounded by his courtiers, feet on a footstool, singing and playing a lyre. At his side, two attentive scribes record the new psalm being composed, while four horn-blowing musicians accompany his chanting, and two courtiers, carried away by the exultant rhythm, clap their hands and dance.

The musical instruments in this illumination accurately reproduce contemporary Anglo-Saxon ones, and show how they were played. The lyre matches examples retrieved from elite burials, such as Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, and Prittlewell, Essex. David is shown stopping some of its strings to strum a chord. The musicians’ wind instruments are of two types: one is a short, curved animal horn; the other—long and straight—is made of hollowed wood sections held together by copper-alloy bands. A similar horn, found in Ireland (Belfast, Ulster Museum, BELUM.A9637), features metal bands incised with decorations recalling those of our illumination, testimony to the close artistic interactions between Britain and Ireland (Breay & Story 2018: 308–11).

Following late-antique conventions, the courtly scene is framed architecturally by an arch supported on stylized columns with whimsical capitals and bases featuring animals. The rigid, geometric patterns of the columns contrast with the curvy, swirling patterns of the arch: these are ‘Celtic’ motifs, symbolizing the sacred (Youngs 2009). Thus, the arch morphs into a celestial vault with radiant stars and whirling constellations (Psalm 147:4), as well as clouds to provide rain for a blessed harvest (v.8). For the psalmist the contemplation of God’s orderly creation is a source of divine inspiration.

References

British Library, Cotton MS Vespasian A.1, available at http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Cotton_MS_Vespasian_A_I [accessed 19 April 2022]

Breay, Claire and Joanna Story (eds.). 2018. Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War (London: British Library)

Youngs, Susan. M. 2009. ‘From Metalwork to Manuscript: Some Observations on the Use of Celtic Art in Insular Manuscripts’, in Form and Order in the Anglo-Saxon World, AD 600–1100, ed. by Sally Crawford, Helena Hamerow, and Leslie Webster, pp. 45–64

Vincent van Gogh

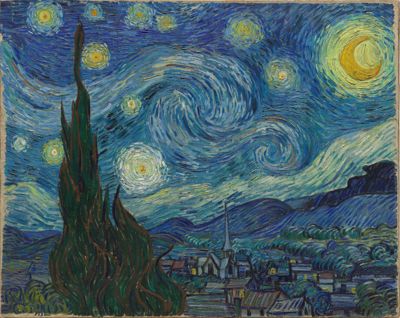

The Starry Night, 1889, Oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). Conservation was made possible by the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, 472.1941, Digital Image ©️ The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Reach for the Sky

Commentary by Anna Gannon

Vincent van Gogh painted Starry Night in 1889, a year before his death, while at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. The scene is dominated by a dynamic vision of bright stars and planets swirling over a tranquil, moon-lit landscape. We see a village and softly-rounded mountains, with fields and trees in the background. In the left foreground, the top of an aromatic cypress gently sways in the wind, rising like incense smoke, or prayer, to the sky (cf. Psalm 140:2). The paint is thickly three-dimensional, conveying light, movement, and energy.

Much has been written about this canvas, the artist’s disturbed state of mind, his religiosity, as well as the eerie correspondence between this depiction of celestial bodies and what space telescopes show us that stars and the trillions of galaxies we have observed—such as the spectacular Fireworks and Whirlpool galaxies—look like.

One fruitful way of approaching Starry Night is through an 1888 letter written by Vincent to his brother Theo, in which the artist talks of his dreamy fascination with stars and with ‘dots on a map’ (representing towns), and how, just as we take a train to visit a place, we will ‘take death’ to visit stars, as they are inaccessible to the living (Letter 638). The artist’s religious longing for such a journey is further hinted at by the centrality of the church, with its tall steeple probing the sky.

A deep contemplation of the glory of the stars—whether the dominant swirling patterns moving through the sky are read as the Milky Way or as God’s ‘sending out his command to the earth’ (Psalm 147:15)—the painting invites the viewer to imagine how it might feel to gain admittance to this dazzling work of God (v.4).

References

Van Gogh, Vincent. 1888. ‘Letter to Theo van Gogh, Arles, c.9 July 1888’, trans. by Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, ed. by Robert Harrison, #506, http://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/18/506.htm [accessed 6 October 2020]

Marc Chagall

Joseph, 1962, Stained glass, Hadassah Hospital, Jerusalem; ©️ 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Steve Jordan / Alamy Stock Photo

Fields of Gold

Commentary by Anna Gannon

He fills you with the finest of the wheat (Psalm 147:14)

In the early 1960s, Marc Chagall created a set of twelve stained-glass windows as his ‘modest gift to the Jewish people’ for the synagogue of the Hebrew University's Hadassah Medical Centre in Jerusalem.

At their dedication, Chagall stated that ‘to read the Bible is to perceive a certain light’ (Harshav 2003: 145). Indeed, the windows are widely admired as a luminous and spiritual biblical paraphrase. They are based on Genesis 49, where Jacob blesses his twelve sons, and Deuteronomy 33, where Moses blesses the original twelve tribes of Israel. The windows are emblematic rather than illustrative of scriptural episodes, each characterized by a dominant colour and a quotation from the individual blessing given to each son. They are arranged in threes around a square, as God commanded their encampment should be around the Tent of Meeting, each tribe with its ensign (Numbers 2:2). Together they mirror the twelve gates of the New (eschatological) Jerusalem through which the prayers of each of the twelve tribes could access God directly (Ezekiel 48:30–34; Revelation 21:12–13).

The window selected for this exhibition is that of Joseph, the ‘prince amongst his brothers’, beloved son of Jacob, who blessed and committed him to God’s mighty help (Genesis 49:22–26). Moses prayed to the Lord that Joseph’s land would yield the best and most abundant produce (Deuteronomy 33:13–16).

The scene echoes the praise of the psalm: in His mighty power and infinite wisdom, God’s blessings and goodness are bestowed in abundance and with attentive care to the whole of His creation below, providing generously for man, beasts, and birds alike. Joseph’s window glows with the rich golden colour of the finest wheat in the fields, while well-nourished flocks feed, and a contented bird nests in a tree, at the lower left. A basket brimming with fruits is nearby.

Jacob compared Joseph to a fruitful plant by a spring: indeed, the tree is anthropomorphic, showing a human face, arms/branches raised in praise, and legs morphing into a tree trunk, whilst a taut bow is a further allusion to Jacob’s words (Genesis 49:22–25).

Above this bountiful scene, two hands from heaven hold a horn, maybe a horn of plenty, testifying to God’s continuous, abundant benediction of the land below, or a musical instrument to sound His praises.

References

Harshav, Benjamin (ed.). 2003. Marc Chagall on Art and Culture (Stanford: Stanford University Press)

Unknown artist, England :

King David and his Musicians from the Vespasian Psalter, 8th century , Manuscript illumination

Vincent van Gogh :

The Starry Night, 1889 , Oil on canvas

Marc Chagall :

Joseph, 1962 , Stained glass

Alleluia First and Last

Comparative commentary by Anna Gannon

Psalm 147 (a post-exilic psalm, as the text implies in verse 2) is one of the final five psalms in the Psalter beginning with the word Alleluia, indicating ecstatic praise.

When the book of Psalms was compiled, some details on presumed authorship and instructions for performance were also included (Staubli 2018: 62). It seems that in the Temple psalms were usually sung by a chorister alternating with a choir, and accompanied by musical instruments and dancing.

Although we do not know exactly how they were originally performed, the Vespasian Psalter miniature brilliantly captures the jubilant thanksgiving and rhythmical praises that are expressed in Psalm 147, which bursts forth with joyful exhortations to sing lauds to the Lord for His goodness and love. Interestingly, the Vespasian Psalter shows a strong emphasis on performative singing, as the manuscript also includes various canticles and hymns.

In our psalm, the exhortation to sing praises and thanksgiving to God is repeated three times (vv.1, 7, 12), creating a tripartite structure. The reasons why lauds are due (in our parlance: political, environmental, and humanitarian) are listed, connected, and expanded on throughout the text.

Foremost, thanks are offered for the restoration and special care of Jerusalem and of its exiled people, able at last to live securely within strong gates, in blessed peace and prosperity. In His compassion and tenderness, God has upheld the lowly and comforted the broken-hearted, and the loving extravagance of God’s unique relationship with Jerusalem is rightly noted.

Praises are due in recognition of God as the Creator of all things: His might is manifested in this world through the amazing natural wonders we observe. The well-ordered stars are the first marvel to be mentioned. Since the earliest of times, stars have been a symbol of afterlife and paradise in many cultures. Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night testifies to the powerful attraction they still hold for us: in his canvas, the stars are huge, and appear to pulse with an irresistible centripetal force that draws us up to them, and ultimately to God Himself.

The psalm acknowledges the Lord’s farsighted involvement in providing the right conditions for the earth to yield food and sustenance: clouds, rain, snow, and frost are all necessary in order for it to produce abundant crops to feed both people and animals. Even the more extreme varieties of weather (snow like wool, hoarfrost like ash, hailstones showered down like bird food; vv.15–17) are subject to God’s directives.

In His mercy, even the raucous young ravens are not forgotten. Because of these mediations, the Lord is lauded as the gracious benefactor of all His creation. The blissful sight of abundant, ripe crops in their golden richness is captured in the window Marc Chagall devised to commemorate the blessings bestowed on Joseph’s land. In the peaceful scene, flocks feed happily, birds thrive—and Joseph himself, rejoicing in this bountiful landscape, acknowledges God’s gifts by raising his hands in thankful prayer.

Central to all these providential interventions is the active ‘word’ of God, which is alluded to eight times, via His commands, His blessings, and His teachings. It is through the word of God—uniquely manifested to Israel through His laws and decrees—that Israel has been set apart from other nations as the chosen people.

We may take comfort in the words of the psalm: God has no pleasure in feats of human strength, but He delights in the humble love, obedience, and collaboration of those who sincerely trust in His positive and transformative purposes. We are encouraged to remember with gratitude that the promise of His steadfast care endures through human history, and to trust that He will grant peace, renewal, and prosperity to us, His new Jerusalem.

References

Staubli, Thomas. 2018. ‘Performing Psalms in Biblical Times’, Biblical Archaeology Review 44.1: 62–63

Commentaries by Anna Gannon