Psalms 149–150

O Praise God in His Holiness!

Unknown artist

King David as Orpheus in a synagogue mosaic, 508, Mosaic, 300 x 180 cm, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Collection the Israel Antiquities Authority; Photo: Abraham Hay ©️ The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Upon the Lute and Harp

Commentary by Rachel Coombes

In the early Byzantine era, it was not uncommon for Jews and Christians to appropriate imagery of Graeco-Roman gods, as this mosaic of David in the guise of Orpheus demonstrates. The synagogue community of Gaza (where this mosaic was discovered) would have been accustomed to Hellenistic imagery. The compelling parallel between the psalmist who drives out King Saul’s demon with his playing, and the Greek hero who tamed wild beasts through his song, probably made the syncretic image-type a particularly popular choice.

In this mosaic fragment, the boyish-looking musician is dressed as a Byzantine emperor (Ovadia 1991: 129–31); he is labelled as ‘David’, and is shown playing a fourteen-stringed lyre (or more likely the closely related kithera). The fingers of his left hand rest lightly on the strings as he strikes them with a small hammer in his right hand. The directional gesture of both his arms invites us to discern the most prominent member of his immediate audience, a lion cub, or lioness. The creature appears, in accordance with the Orphic legend, to be bowing its head in docile submission to the music.

For the synagogue worshippers, King David was the pre-eminent biblical musician (‘the sweet singer of Israel’; 2 Samuel 23:1 CJB), so intimately was his identity tied to the Sēfer Tehillīm (book of Psalms).

The Hebrew word tehillīm can be translated as ‘praises’ (without musical connotations), while ‘psalms’ derives from the Greek word psalmoi, meaning ‘instrumental music’. These slight divergences of meaning come together at numerous points in the psalm collection, including in Psalm 150:3, in which the psalmist summons the worshiper to ‘Praise him with lute and harp’ (see also Psalm 149:3).

Unlike Orpheus’s lyre, which had ‘elevating powers’ that allowed it to continue playing even after Orpheus’s death (Bernstock 2006: 35), David’s harp was an earthly object that relied on the Israelite king’s accomplishment. In David’s case the divine gift was not the instrument, but the ability to express his gratitude to God through music.

References

Bernstock, Judith. 2006. Under the Spell of Orpheus: The Persistence of a Myth in Twentieth-century Art (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press)

Friedman, John. 1960. Orpheus in the Middle Ages (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

Ovadia, Asher. 1981. ‘The Synagogue at Gaza’, in Ancient Synagogues Revealed, ed. by Lee I. Levine (Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society)

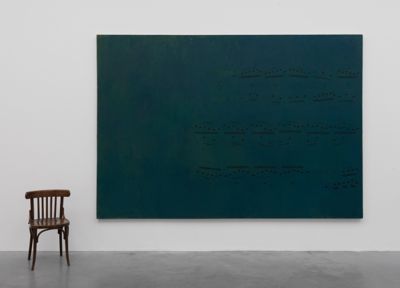

Jannis Kounellis

Untitled, 1971, Oil on canvas, 220 x 316.9 cm (support), Tate; Acquired jointly with the National Galleries of Scotland through The d'Offay Donation with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund 2008, AR00497, ©️ 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome; Photo: ©️ Tate, London / Art Resource, NY

Sing to the LORD a New Song!

Commentary by Rachel Coombes

Before viewers can begin to decipher the musical score printed on the canvas of Jannis Kounellis’s ensemble Untitled, they notice the adjacent empty chair.

The lack of occupant is significant, acting as a sort of provocation. Once one does discern that the notes imprinted on the green-blue ground are a fragment of J.S. Bach’s St John Passion, the chair seems to take on added import, perhaps functioning as an indexical sign, or trace, of musical performance. Indeed, when this work was first displayed (at the Modern Art Agency in Naples), a cellist occupied it, playing the printed musical fragment over and over again.

The work of Kounellis (a Greek–Italian best known for his involvement in the Arte Povera movement) was often hybrid in nature, sitting somewhere between sculpture, installation, and performance art. As an example of this hybridity, Untitled offers a way in to considering the ontological nature of music itself. A work of music is materialized in its physical score (as symbolized by Kounellis’s canvas), thus becoming a historical ‘object’. But music is also an action which generates meaning in real time, in a specific environment, through live performance (as connoted by Kounellis’s addition of the chair).

What might the reaction of the congregation have been at Leipzig’s Nikolaikirche on Good Friday, 1794, when Bach’s work was first performed? Sadly, no documentary evidence survives. But today’s Western Christian musical worship owes much to the fresh spirit of the Lutheran tradition that nourished Bach, and which relied so heavily on the Psalter for its rich hymnal practice. The Passion’s opening chorus, ‘Oh Lord, our Lord, how majestic is thy name in all the earth!’ borrows its words from Psalm 8, which shares the same spirit of exultant praise as Psalms 149 and 150. The story of Christ’s Passion is thus framed at the very beginning, not simply as a narrative of suffering, but as a vision of divine glory in which Christ’s death is a triumphal act.

‘Sing to the Lord a new song’, commands the psalmist in Psalm 149 (repeating a summons that also begins Psalms 96 and 98); Kounellis’s empty chair also functions as a kind of imperative. The work lies ‘dormant’ until ‘activated’ by the beholder.

Thus, it seems to invite new and endless completions. And the Psalms are like that too, continually awaiting new voices to give them utterance in fresh configurations, styles, and contexts.

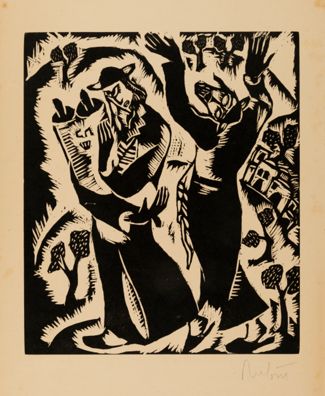

Reuven Rubin

Dancers of Meron, 1923, Woodcut, 330 x 280 mm, Rubin Museum; ©️ Rubin Museum Foundation

The High Praises of God

Commentary by Rachel Coombes

Let them praise his name with dancing. (Psalm 149:3)

The Romanian-born artist Reuven Rubin completed his ‘Seekers of God’ woodcut series, from which The Dancers of Meron is taken, in 1923, shortly after moving from Europe to Palestine. It anticipates his better-known oil painting of the same name from 1926.

As with much of Rubin’s work, the woodcut series illustrates his experience of the Zionist optimism engendered by the 1917 Balfour Declaration, which gave political impetus to the possibility of a Jewish national home. The ecstatic gesture of the figure on the right was prominent within the choreographic vocabulary of Rubin’s friend the Romanian-born dancer-choreographer Baruch Agadati, who was responsible for establishing Hassidic dance traditions in Palestine following his own move there in the early 1900s (Manor 2002: 73–89).

Rubin developed an artistic idiom derived in part from German Expressionism and Russian neo-Primitivism to express a sense of ‘rootedness’ in Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel). ‘Rumania was forgotten, New York far away … In Palestine there was sunshine, the sea, the halutzim (pioneers) with their bronzed faces and open shirts … A new country, a new life was springing up around me … The world around became clear and pure to me. Life was stark, bare, primitive’, the artist proclaimed (Zalmona 2013:44).

The woodcut medium—with its associations of ‘primitivism’, and its discipline of simplification and elimination of extraneous detail—helped Rubin to distil the essential from his experience. The rhythmic continuity between the human forms and the landscape not only accentuates the figures’ gestures, but also serves to tie them into their environment.

‘Let Israel be glad in his Maker, let the sons of Zion rejoice in their King. Let them praise his name with dancing’ read verses 2 and 3 of Psalm 149. The two men in this woodcut enact the close association between communal dancing and worship among the Hassidic Jewish community, who make the annual pilgrimage to Mount Meron on the festival of Lag ba-omer.

While the figure on the left embraces the Torah scroll as he sways in a votive reverie, his companion raises his hands, as if overtaken by a spiritual frenzy. Their gestures may be complementary: holding Scripture close to your heart can at the same time open you to the heavens.

References

Manor, Dalia. 2002. ‘The Dancing Jew and Other Characters: Art in the Jewish Settlement in Palestine During the 1920’, Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 1.1: 73–89

Zalmona, Yigal. 2013. A Century of Israeli Art (Surrey: Lund Humphries)

Unknown artist :

King David as Orpheus in a synagogue mosaic, 508 , Mosaic

Jannis Kounellis :

Untitled, 1971 , Oil on canvas

Reuven Rubin :

Dancers of Meron, 1923 , Woodcut

Israel’s Songbook

Comparative commentary by Rachel Coombes

This exhibition focusses on the celebratory tone and imperative call to praise—through music—that define Psalms 149 and 150.

Of course, one of the most valued aspects of the Psalter is its embracing of the full range of human experience, from deep lament (Psalm 88) to thanksgiving (Psalm 107), and even raw vengeance (Psalm 109).

But the uninhibited summons to worship found in these final two psalms (which conclude the book’s fivefold group of doxologies) condenses the underlying message of the psalm collection: that it is ‘the whole duty of humans … to praise and enjoy God (Brueggeman & Bellinger 2014: 619). The New Testament, too, celebrates music’s importance in fulfilling this vocation: Paul says to the Colossians:

Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly, teach and admonish one another in all wisdom, and sing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs with thankfulness in your hearts to God. (Colossians 3:16)

It is no wonder that European polyphonic music from the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century consisted of Psalm settings. The Psalms’ poetic structures indicate their origins as songs, and made them attractive to composers in the centuries to follow. Imperative calls to pick up instruments abound throughout the Psalms but are most prominent in these final two texts: ‘Let them praise his name with dancing, making melody to him with timbrel and lyre!’ (Psalm 149:3); ‘Praise him with trumpet sound … with lute and harp. Praise him with … strings and pipe [organ]’ (Psalm 150:3–4); ‘Praise him with sounding cymbals: praise him with loud clashing cymbals’ (Psalm 150:5). Here, in the concluding psalm, we have a kind of crescendo, a musical intensification that ends with the dual reference to the cymbals.

In their different ways, the three works in this exhibition remind us of the symbolic and material centrality of musical practice to Jewish and Christian worship. The sixth-century CE King David–Orpheus mosaic, set within the floor of a synagogue, is an emblematic prompt for worshippers to praise God through music ‘in his sanctuary’ (Psalm 150:1)—in the Temple. Just as King David’s musicianship inspired the Temple’s priests to perform the original psalms (1 Chronicles 15:16–24), so the Byzantine depiction of a performing David within the walls of the synagogue could act as an inspiration to music-making for later generations.

The conductor John Eliot Gardiner once described the opening chorale of Bach’s St John’s Passion (the work inscribed on the canvas of Jannis Kounellis’s Untitled) as a ‘portrayal of Christ in majesty like some colossal Byzantine mosaic’ (Ross 2021). Like the imposing iconic status of a Byzantine mosaic, this musical passage acts as a moving witness to God’s grandeur. The reframing of Bach’s musical masterpiece as an art gallery installation in Untitled emphasizes its position as a cultural artefact—as a musical ‘icon’—that has transcended its culturally specific origins in the Reformation. Luther once commented: ‘Music is a fair and lovely gift of God … Next after theology, I give to music the highest place and the greatest honour’ (Bainton 2013: 352). Indeed, Bach’s religious masterworks are seen by many as vehicles of profound spiritual revelation, but it is usually as contemplative listeners, rather than participants, that we appreciate it. Kounellis’s empty chair, however, prompts the viewer to consider what sort of participation might be available to them in this music.

Reuven Rubin’s Dancers of Meron woodcut does not feature an act of music-making per se, but rather the bodily manifestations of its motifs and rhythms. It draws our attention to the participatory element so central to religious musical traditions, as well as to its potential for bodily expression. More specifically, the work signifies the embeddedness of music within the Hassidic tradition. It could perhaps be a memory, or a reverie, of the music of the Temple that compels these two Hassidic men to move, and, no doubt, to vocalize the scripture melodically.

The powerful physical and emotional release that comes with lifting our voices in unison provides the backbone for much religious worship today, stirring us in much the same way as the Israelites in the Temple were moved by the ineffable exultation of psalmody.

The powerful physical and emotional release that comes with lifting our voices in unison is felt by contemporary congregations across the world in much the same way as the ineffable exultation of psalmody moved the Israelites in the Temple.

References

Bainton, Roland. 2013. Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (New York: Abingdon Press)

Brueggemann, Walter, and William Bellinger, Jr. 2014. Psalms: New Cambridge Bible Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Ross, Alex. 2017. ‘Bach’s Holy Dread, 2 January 2017’, www.newyorker.com [accessed 19 June 2021]

Commentaries by Rachel Coombes