Matthew 9:9–13; Mark 2:13–17; Luke 5:27–28

The Calling of Matthew

Works of art by Maître François, Marinus van Reymerswaele and Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Marinus van Reymerswaele

The Calling of Saint Matthew, c.1530, Oil on panel, 70.6 x 88 cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid; 332 (1930.96), HIP / Art Resource, NY

A New Accounting

Commentary by David Hoyle, MBE and Beth Williamson

Marinus van Reymerswaele painted many representations of moneychangers and tax collectors. He was famed as an artist who could effectively demonstrate the temptations of money and wealth, and his compositions were so admired that they were widely copied.

In this painting, we must assume that Jesus has already indicated that he wants Matthew to follow him. The Saviour, at left, is turning away, as though he is about to leave. But there appears to be a contradiction: his left hand is raised as though still in speech.

Hands are eloquent in this picture. While Matthew is located at the far right, his hand is extended so that it occupies the very centre of the composition. This seems significant. It might be an invitation to think about what has just happened in his encounter with Jesus.

The upturned hand might indicate that, not long ago, he had made as though to ask Christ to pay his tax. We notice the bowl of coins right above this hand. Meanwhile, the piled-up receipts, account books, and cash box all speak of Matthew’s obligations as a tax collector.

However, Matthew’s left hand, which mirrors Christ’s raised left hand, shows that however unexpected or unlikely, the Call of Matthew has already happened, and by imitating Christ Matthew is already following him. With that left hand, Matthew is taking hold of his hat. This action, and the fact that he leans forward, show that he is getting up to leave the room and follow Christ—obeying the call.

The hat’s elaborate appearance, which is an indication of Matthew’s wealth, along with the expensive shot-silk and velvets that he wears, shows that he is in transition from his old ‘worldly’ life to his new vocation. In following Christ, he will be giving up those trappings of wealth, and making a big change in his life.

There is little here that indicates Matthew’s future identity as an evangelist, although the pen and ink pot at the far right of the desk will be tools that he can also use in his future as a writer. The noticeboard above Matthew’s head enhances the impression that he is about to leave one employment for another: what is written on that board is not monies owed, or payment dates, but the references to this episode in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke.

References

Van der Stock, Jan. 2003. ‘Reymerswaele, Marinus van’, Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T071704

Vlam, Grace A.H. 1977. ‘The Calling of Matthew in Sixteenth-Century Flemish Painting’, The Art Bulletin, 59.4: 561–70

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1599–1600, Oil on canvas, 22 x 340 cm, Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome; Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

A Bringing to Light

Commentary by David Hoyle, MBE and Beth Williamson

Uncertainties abound here. It is not immediately clear which of the figures around the table is Matthew. However, the appearance of the saint in two companion works in the same chapel (The Inspiration of Saint Matthew and The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew) suggests that Matthew is the bearded figure in the Calling.

Matthew is himself not clear who is being called, as indicated by his quizzical expression, and his own ambiguous pointing gesture. Light streams in and illuminates his face, but not through the window that is visible. It comes from an unseen source above the figure of Christ, who stands to the right, partially obscured behind St Peter (the figure with his back to the viewer).

The upper edge of the shaft of light ends at the head of the youth in red and yellow, and makes us wonder for a moment who is being picked out. Christ’s indeterminate pointing gesture adds to this uncertainty.

It has often been remarked that Christ’s gesture echoes the hand of Adam in Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel. It is difficult to say whether this visual quotation is iconographically or theologically significant. It may be that Caravaggio is simply making a reference to another well-known painting that would have been known by the Roman ecclesiastical elites, including the Contarelli Chapel’s patron, Cardinal Matthieu (i.e. ‘Matthew’) Cointerel (thus the chapel’s dedication).

In this Roman context, Peter’s position between the viewer and Christ is likely to suggest his role as the archetypal apostle. Here, as in his ordained role as leader of the Church on earth, he mirrors Christ, and helps us to see and understand his purposes.

The gestures and gazes here communicate a more vivid question, with a less certain answer, than we see in many other treatments of the theme. Smart clothes in rich fabrics, coins, a velvet hat with a brooch, all indicate that a lot must be given up if this call is to be heeded. Indeed, Matthew’s martyrdom, depicted on the facing wall of the chapel, tells us that it cost him everything.

But at this point the outcome is not certain. At the heart of this painting is uncertainty and strong contrast: contrasts of dress, of darkness and light, of belonging and identity. There are two possible outcomes. The stress falls on the choice Matthew must make and on the mystery of divine action.

References

Gilbert, Creighton. 1995. Caravaggio and His Two Cardinals (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State Press)

Pericolo, Lorenzo. 2011. Caravaggio and Pictorial Narrative (London: Harvey Miller Publishers)

Puglisi, Catherine. 1998. Caravaggio (London: Phaidon)

Maître François

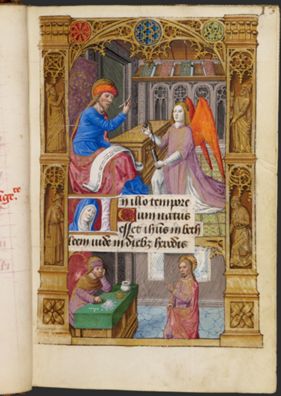

Portrait of Matthew the Evangelist, and The Calling of Matthew, illustrating an extract from Matthew’s Gospel in a Book of Hours (Use of Bourges), c.1470–80, Manuscript illumination, 174.6 x 127 mm, The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; Bodleian Library MS. Canon. Liturg. 43, fol. 013r, Photo: Courtesy of the University of Oxford

An Altered State

Commentary by David Hoyle, MBE and Beth Williamson

This page from a fifteenth-century prayer book, by an anonymous illuminator known as Maître François, illustrates an extract from the beginning of Matthew’s Gospel. It was, by this date, traditional to have four gospel extracts at the start of such prayer books, and common for such extracts to be illustrated with a portrait of the appropriate evangelist.

However, it is usual to have an image showing only the evangelist as evangelist. It is rare to encounter the incorporation of an additional scene that refers to an episode from the saint’s life. Here, in the lower register, we see Matthew engaged in his work as a tax collector, being summoned by Christ. The addition of this second, smaller, illumination appears almost as a gloss upon the upper image, and clearly indicates the shift in vocation that has taken place.

In each of these scenes Matthew is wearing different clothing, and is in different rooms, with different furnishings. In the lower scene, Matthew sits at a wooden table with simple detailing, which is covered with a cloth. The piles, and lines, of gold and silver coins indicate that he is sorting and counting money. His head resting on his hand appears to suggest that he had, just a moment before, been concentrating on that task.

Now his attention is caught by Christ, who points at Matthew in an authoritative and direct gesture. There is no mistaking his intention or the object of his attention.

Matthew’s new vocation is surprising, and unexpected: that is a lot of money that he will need to leave behind. And yet, the outcome is not in doubt, as the main image of Matthew as evangelist confirms. The room in the upper scene has ecclesiastical detailing: a collection of books rests on a structure with elaborate gothic tracery that evokes church windows; the floor is furnished with painted tiles. The table in this room appears to be carved stone, with its surface being a large piece of unbroken stone (is it perhaps to be read as an altar?). It is arranged in a very similar manner to that in the image of Matthew as tax collector. This allows us to draw connections, and contrasts, between one occupation and the other: after his calling he puts his skills to another use, with new energy, writing his Gospel.

References

Backhouse, Janet. 1988. Books of Hours (London: The British Library)

Wieck, Roger. 1997. Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art (New York: George Braziller, in association with the Pierpont Morgan Library)

Marinus van Reymerswaele :

The Calling of Saint Matthew, c.1530 , Oil on panel

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio :

The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1599–1600 , Oil on canvas

Maître François :

Portrait of Matthew the Evangelist, and The Calling of Matthew, illustrating an extract from Matthew’s Gospel in a Book of Hours (Use of Bourges), c.1470–80 , Manuscript illumination

One Life Exchanged for Another

Comparative commentary by David Hoyle, MBE and Beth Williamson

A key message suggested by these three artworks and the passages on which they comment, is that of improbability: Jesus calls unlikely, unsuitable people to be his followers.

Matthew’s status as a tax collector makes him a very surprising candidate to become a disciple, and, later, an evangelist. Although tax collectors were usually members of the local population, they worked as customs officials for the Roman Empire. This made them particularly despised as a class, understood to be traitors, collaborators, and cheats: they had to pay an expected revenue and then recoup their expenses and profit, a system that encouraged profiteering.

The Scriptures emphasize the dubiousness of the social role played by people like Matthew. And likewise, in each of the artworks in this exhibition, the tax collector (whom Mark and Luke call Levi, and Matthew calls Matthew) is shown to be not quite the sort of person who seems a likely disciple of Christ.

Yet, while acknowledging this unsuitability, the Gospels dispense surprisingly quickly with his call: Christ summons, Matthew follows. It takes just one or two verses in each passage. Each then goes on immediately to describe the dinner at which Christ is criticized for eating with tax collectors and sinners (Luke says this takes place at Levi’s house, while Matthew and Mark are less clear on whose house it is), and at which he declares that he has not come to call the healthy (i.e. the righteous) but the sick (Matthew 9:12).

Artists, by contrast, are not often interested in the feast; depictions of the Call of Matthew are much more common. All three artists here seem well aware of Matthew’s unsuitability. Each of them shows us the trappings of a lucrative way of life: his money and rich clothing. All of them want us to acknowledge that one lifestyle gives way to another.

They also make a point that the texts do not. They want us to think about the choice Matthew makes. In doing this, they shift the centre of agency. In Scripture, Christ calls and Matthew follows; the Lord is irresistible. These artworks invite us to wonder: what will this man, Matthew, do? What does this choice mean for him?

Each scriptural passage describes the call in a similar way. However, each of these images draws out slightly different implications of the episode. In Maître François’s manuscript illumination we see two rooms, in two separate images: one life exchanged for another; one accounting replaced with another. In Marinus van Reymerswaele’s panel, Christ is inviting Matthew to go with him into the new life we can see through the door. We see Matthew moving: there is an immediacy about it. In Caravaggio’s painting for the left-hand wall of a chapel in a Roman church, there is a tight focus on the depicted interior in which the action takes place. Nothing can be seen of any potential alternative life outside. The question is just in the process of being asked. Matthew is not even sure to whom the call is directed, and we are not certain what he is going to do. Some of the answers to this uncertainty are supplied by the two companion paintings on the other walls of the chapel in which this work is installed: the Inspiration of St Matthew and his Martyrdom. But the picture space of Caravaggio’s Calling of St Matthew concentrates closely on the drama and possibility of a call and what might follow.

All three paintings in this exhibition focus on the suddenness and improbability of the call. We are invited to consider the scale of the challenge Matthew faces with this transformation in his life and work. All three of the Gospel texts are notably concise. It is striking how fruitful painters find such a brief text, however, and how they are determined to dig into that moment of uncertainty, and into Matthew’s decision. Each of the paintings here invites us to examine deeply what it means for Matthew to listen to the words ‘Follow me’ (Matthew 9:9; Mark 2:13; Luke 5:27), and to respond.

References

Fanthorpe, U. A. 1986. Getting it Across, in Selected Poems (London: Penguin), p. 72

Fitzmyer, Joseph A. 1970. The Gospel According to Luke I–IX, The Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday), p. 589

Williams, Rowan. 2016. Being Disciples: Essentials of the Christian Life (London: SPCK)

Commentaries by Beth Williamson and David Hoyle, MBE