Matthew 9:20–22; Mark 5:24b–34; Luke 8:42b–48

The Woman with the Issue of Blood

Unknown artist

Columned Sarcophagus with Biblical Scenes (Columnar sarcophagus of Agape and Crescentianus), c.330–60, Marble high relief, 59 x 150 cm (whole sarcophagus), Museo Pio Cristiano, Vatican City; MV_31558_0_0, Lanmas / Alamy Stock Photo

Surprise Encounters

Commentary by Joan Taylor

There are seven scenes in the surviving three fragments of this fourth-century sarcophagus relief, now located in the Vatican's Museo Pio Cristiano, each separated by columns with a twisted decoration. Four scenes show a youthful, curly-haired, beardless Christ who performs miraculous healings. On the far left, Jesus touches his staff on the head of a child wrapped up for burial (probably Lazarus); others apparently show the healing of the man born blind (here a boy), the miracle of Cana, and the story of Susanna and the Elders from the Greek Septuagint additions to Daniel (Smith 1993).

The healing of the woman with an issue of blood is a popular subject in surviving Roman sarcophagi, occurring thirty-eight times, sometimes blended with the raising of Lazarus (Jefferson 2014: 95, n.21). However, the scene in this sarcophagus is highly unusual in showing Christ viewed from behind, walking away from us, as also from the woman. We have her view of Jesus, from behind.

Christ has his left foot raised, and looks back over his right shoulder. He has been alerted to the woman’s touch. Though his foot is still in the air, such that we can even see its sole, he turns to touch the top of her head.

The woman’s profile is calm, veritably expressionless, but surprise is the key to the sculptor’s comment on this scene: Christ’s surprise and, perhaps, ours. Her seizure of the bottom of his long tunic catches and turns him in mid-stride. Our surprise is perhaps that we are so emphatically placed in her position. This image seems to urge us to reach out to Christ in faith, as she does, in the expectation that he will respond.

References

Jefferson, Lee M. 2014. Christ the Miracle Worker in Early Christian Art (Minneapolis: Spark House)

Smith, Kathryn A. 1993. ‘Inventing Marital Chastity: The Iconography of Susanna and the Elders in Early Christian Art’, Oxford Art Journal, 16.1: 3–24

Taylor, Joan E. 2018. What Did Jesus Look Like? (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark)

Unknown artist

Christ and the Woman with the Issue of Blood, 3rd century, Tempera on plaster, 62 x 56 cm, Catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus, Rome; Wikipedia

Wide-Eyed Wonder

Commentary by Joan Taylor

This late third-century painting is one of only two surviving scenes in the Roman catacombs of the healing of the woman with an issue of blood. The woman’s left knee is bent and her right knee is touching the ground, as if she has just dropped into this position. The painter captures the very moment of the woman’s healing as told in Matthew 9:20–22, which takes place just after Jesus speaks, as a result of his deliberate action.

Jesus’s mantle is plain and undyed, worn in a fashion typical of the time, without luxurious trappings or colour. The string which the woman grasps at its hem is the artist’s interpretation of what is referred to as the ‘edge’ (Greek: kraspedon) of Jesus’s mantle (not mentioned in Mark’s account). This was sometimes used as a technical term for what in Hebrew is called a tsitsith, a tassel on mantles of Jewish men (Numbers 15:38 LXX) (Taylor 2018: 180). The artist is, very unusually, attempting to render this feature (though not accurately, as the tassel would not have been where the woman seizes it).

Despite the painting’s simplicity (the crowd mentioned repeatedly in the Gospel accounts has not been included), the vivid movement in this work implies a poignant interaction between the two people shown. Christ is smiling, and is gesturing backwards with his right hand towards the woman as he swings around. The woman’s wide eyes in the painting tell us not only of her fear but also of her wonder. It is almost as if she is feeling the impact of the sensation of being healed.

In terms of the Gospel story, the painter asks viewers to exclude from consideration all the other people mentioned—the crowd and Jesus’s disciples—and to focus purely on the extraordinary moment of the woman’s initiative. She is so full of faith and so assertive that she grasps hold of Jesus’s clothing as he walks. She is rewarded by Jesus’s compassionate response and miraculous cure.

Identifying with her, we, too, may be wide-eyed in remembering this miracle.

References

Taylor, Joan E. 2018. What Did Jesus Look Like? (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark)

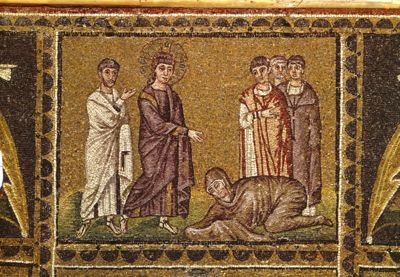

Unknown artist

Christ Healing the Woman with the Issue of Blood, 6th century, Mosaic, 1.37 x 1.15 m, Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna; Scala / Art Resource, NY

I Will Seek Your Face

Commentary by Joan Taylor

Here, on a background of sparkling gold tesserae, a woman, veiled and dressed in beige-brown clothing, is shown kneeling. Her forearms are stretched forwards from underneath a cloth towards a young Christ. Beardless and with long, golden, curly hair, this Christ has the conventional attributes of an emperor. His clothing is royal: a purple tunic with long sleeves edged in gold stripes is overlaid with another with golden stripes running from shoulder to hem. Over this is a purple mantle. His right hand is stretched out authoritatively. Even his halo—a gold cross with blue gems—is worn like a crown.

Behind Christ is a bearded man dressed in white, with purple trimming. He gestures as if explaining something. But what?

This sixth-century image forms part of a series of thirteen panels depicting Christ’s miracles and parables in the upper register of a wall mosaic in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (Deliyannis 2014: 152–75). Christ’s royal clothing identifies him as God’s kingly Messiah, the divine ruler on earth. The white-clad man, also found elsewhere in the series, represents an evangelist. This indicates that the scene is only truly understood by reference to the Gospel story.

But in fact, this story is blended with another, and the key is in the cloth that covers the woman’s hands. Unrecognized hitherto, this is the earliest visual depiction of the story of Veronica’s cloth, as told in the most ancient versions of the seventh/eighth-century Vindicta Salvatoris and Cura Sanitatis Tiberii (Taylor 2018: 27–38). The haemorrhaging woman was understood to have been named Berenice (Greek), or Veronica (Latin). As a reward for her faith, Christ effects a miraculous self-portrait on the cloth. Christ’s gesture here then invites Veronica to give him the cloth. It is not a blessing, since elsewhere in the panels Christ blesses with two fingers; here his hand is wide open, fingers apart.

Ultimately, this asks us to think of the power and generosity of Christ: miracle-maker supreme.

References

Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf. 2014. Ravenna in Late Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Taylor, Joan E. 2018. What Did Jesus Look Like? (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark)

Unknown artist :

Columned Sarcophagus with Biblical Scenes (Columnar sarcophagus of Agape and Crescentianus), c.330–60 , Marble high relief

Unknown artist :

Christ and the Woman with the Issue of Blood, 3rd century , Tempera on plaster

Unknown artist :

Christ Healing the Woman with the Issue of Blood, 6th century , Mosaic

Beneath the Surface

Comparative commentary by Joan Taylor

The New Testament presents three versions of this episode. In Mark’s version, the woman knows what has been done to her before Jesus asks ‘Who touched me?’ At his question, Mark 5:33 tells us that she ‘came in fear and trembling and fell down before him, and told him the whole truth’.

The sixth-century mosaic in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo is remarkable for combining the Gospel story with the tradition of Veronica, so the moment of the woman’s explanation in front of Jesus is married with her proffering a cloth on which Christ would reward her faith: Christ says, ‘Daughter, your faith has made you well; go in peace, and be healed of your disease’ (Mark 5:34). While both Matthew (9:20–22) and Luke (8:43–48) have shortened versions of this whole story, the woman’s self-revelation is omitted in Matthew, and Jesus turns to see the woman. Luke, on the other hand, builds up the moment with more detail: ‘And when the woman saw that she was not hidden, she came trembling, and falling down before him declared in the presence of all the people why she had touched him, and how she had been immediately healed’ (Luke 8:47). The Ravenna artist takes Mark and/or Luke as the basic text for this portrayal of Christ’s compassion and miracle-making power. The image actually gives us a double miracle: Christ had already made the woman well when the power went out of him without his own deliberate action, but he is about to effect an image of himself on the cloth. We are held between two wonders.

In the late third-century wall painting from the catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus, by contrast, the painter is commenting on Matthew’s version of the story: ‘Jesus turned, and seeing her he said, “Take heart, daughter, your faith has made you well.” And instantly the woman was made well’ (Matthew 9:22).

In the fourth-century sarcophagus relief, it is also Matthew’s version that is shown, in that Jesus turns around and speaks to the woman. In most sarcophagi the woman is shown as very compact, at Christ’s feet, almost curled up into a ball and squashed into the edge of the scene, but here she is not as small as elsewhere, and she literally stops Jesus in his tracks. In addition, the sarcophagus’s juxtaposition of the stories of Christ’s healing with Susanna and the Elders (recounted in the Greek Septuagint additions to Daniel) creates an intertextuality that suggests that the woman’s faithful action and assertion of her touch correlates with Susanna’s faithful virtue and assertion of her innocence: both are rewarded with divine actions. Daniel, sitting on a judgement seat in the centre, signifies the just discernment of God and the action of the Holy Spirit (LXX Daniel 13:44–46).

The sarcophagus image removes the crowd and disciples, but we do still have an accompanying figure, as in the Ravenna mosaic, with a scroll: the evangelist who tells the story, and who can also somehow be read as a companion within the story. In two of our three images then, the authors of the Gospel texts are brought out of the shadows to stand in the scene, as if they are not so much long-gone writers who remembered what they saw as living storytellers in front of a contemporary audience.

As for Christ himself, he is a standing, active figure in all three scenes: the miracle-maker, the healer, and the bearer of divine power. The Ravenna mosaic asks viewers to see him as not only royal, in terms of his clothing, but also as godly: he has the golden locks of Dionysus (Mathews 1999: 116–19, figs 88, 89; Taylor 2018: 90–98). Likewise, the sarcophagus shows him as divine with similar curly hair and good looks. However, in the catacomb painting his power is not obvious from his appearance: he is dressed plainly and his face and hair are ordinary. His power is invisible, less expected; it is all shown in the woman’s wide eyes. Her faith is made all the more remarkable by the fact that she has known what lies beneath the surface.

References

Mathews, Thomas F. 1999. The Clash of Gods: A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Art, Revised and expanded edition (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Taylor, Joan E. 2018. What Did Jesus Look Like? (London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark)

Commentaries by Joan Taylor