Matthew 9:35–38; Mark 6:34; Luke 8:1; 10:2

Christ’s Compassion

Guillermo Galindo

Ropófono, 2013, Wood, contact microphones, immigrants clothing, 91 x 122 x 91 cm, The Rollins Museum of Art, Florida; Museum purchase from the Michel Roux Acquisition Fund. 2018.19, ©️ Guillermo Galindo; Image courtesy of the artist

The Unharvested Many and the Harvested Few

Commentary by Ena Heller

Guillermo Galindo (b.1960) is an experimental composer, and a visual and performance artist. Trained as a composer in Mexico City, his multi-media practice focuses on erasing conventional limits between art forms. Indeed, the sculpture Ropófono exists at the intersection of fine art, music, and performance. It has been defined as a ‘three dimensional sculptural cyber-totemic-sonic object’ (YBCA 2022); when fully used, it is equally an assemblage that includes found objects and a musical instrument that the artist plays during performances.

Ropófono is part of Border Cantos, a collaboration with photographer Richard Misrach which brought together Misrach’s photographs of the US–Mexico border and Galindo’s sonic sculptures created from clothing and objects left behind by refugees attempting to cross it. Together, they document, visualize, and give voice to the human aspect of the immigration crisis.

The title is an invented word, a play on the Spanish words for clothing (ropa) and gramophone (gramófono). The loom-shaped object (a powerful symbol of home in Latin America) is made of several items of clothing found at the border, tied around a wooden frame; when the loom is turned, the rubbing of the fabric against the wood creates a sound which is amplified by contact microphones attached to the structure. The instrument gives voice to people whose names, stories, and even fate after they entered the US are unknown to us. They represent the great multitude of the ‘harassed and helpless’ (Matthew 9:36) in need of a shepherd, of recognition, and of an amplified voice.

They are many. Galindo has ‘harvested’ just a ‘few’ (Matthew 9:37) of their traces, noting that his work is ‘meant to enable the invisible victims of immigration to speak through their personal belongings’ (Misrach & Galindo 2016: 193). The music, alongside the visual presence of the object, memorializes those often-invisible victims.

References

Misrach, Richard and Guillermo Galindo. 2016. Border Cantos. Photographs and text by Richard Misrach. Instruments, sound installations, scores, and text by Guillermo Galindo. Introduction and Epilogue by Josh Kun (New York: Aperture)

‘Guillermo Galindo Biography’. 2022. Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA), available at https://ybca.org/artist/guillermo-galindo/ [accessed 5 January 2023]

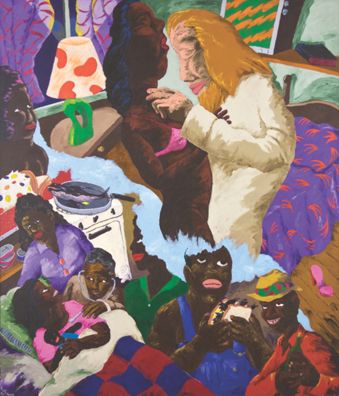

Robert Colescott

Modern Day Miracles, 1988, Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 182.9 cm, Rubell Museum, Miami; ©️ 2023 The Robert H. Colescott Separate Property Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo: Courtesy Rubell Museum, Miami and Washington DC

Sheep in Need

Commentary by Ena Heller

Robert Colescott (1925–2009) was an American painter, printmaker, and teacher best remembered today as disruptor of the art-historical canon by appropriating iconic paintings and reimagining them to include Black figures. The intention was to make visible those who have been traditionally invisible not only in the history of art, but also in American history more generally (Platow & Simms 2019).

Modern Day Miracles is in many ways typical of Colescott’s work from the 1980s, when he turned to tougher, often more political, subjects, while also introducing biblical and mythological stories or symbolism into his works. At the same time, the compositions became more crowded, more dynamic—people from different eras, narratives, or cultures are brought together, overlapping, often clustered in the foreground, as if urging us to pay attention; to see them.

There is an urgency conveyed in such compositions, the reason for which becomes clearer when considering the subject matter. Here, a large Jesus figure, robed in white, stands out in the middle right ground, his eyes closed, his hand touching a Black woman directly in front of him. The figures in the foreground, although spatially closer to us, are significantly smaller than the two central figures, as if to reinforce their relative invisibility. Several scenes are described here: a bedridden woman is being examined by a doctor with a stethoscope, another female figure standing by her side; next to them a man is eating, while a smiling young boy looks on; further back, a woman is cooking a fish on the stove. The entire scene is lit by one lamp on the bedstand, its colourful lampshade one of several vibrant colours punctuating the composition.

Jesus’s presence in this otherwise domestic scene, combined with the painting’s title, emphasizes his message of compassion for all those who are ‘harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd’ (v.36). In an indictment of ongoing inequality, the painting suggests that the modern-day ‘miracle’ is the very fact that Black people have access to healing and medicine, to food and electricity.

Dirk Vellert

Christ Preaching in the Synagogue, with the Pharisees Bringing the Woman Taken in Adultery, c.1523, Pen and brown ink, brush and grey ink; framing line in pen and brown ink, by the artist, 25.8 cm diameter, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2013, 2013.926, www.metmuseum.org

Every Infirmity

Commentary by Ena Heller

Dirck Jacobsz. Vellert was a painter and printmaker active in Antwerp c.1511–c.47. We know that he was a master of the painters’ guild of St Luke and that he took on pupils. Although no paintings have been securely attributed to him, a relatively large number of drawings have (Konowitz 1997). Many of them are designs for stained glass windows—the part of his practice for which he seems to have been most famous.

One such drawing is Christ Preaching in the Synagogue and the Pharisees Bringing the Woman taken in Adultery. The design would have fitted a roundel, common in contemporary architecture as either a stand-alone window or part of a multi-panelled one.

In the centre left foreground of the drawing, Jesus is shown on a bench in the act of preaching, surrounded by a circle of people seated on the ground. Several other figures are standing further back, observing the scene from afar, engaged in conversation. The architecture, though ostensibly depicting a synagogue, is in fact that of a contemporary church, complete with pier statues under elaborate canopies and a rood screen in the background, crowned by a large scale, enthroned statue.

A group of men and a woman is entering from the right, their movement suggesting that the woman is being pushed forward, possibly against her will. They are bringing her towards Jesus for judgement. This has been interpreted as depicting the Pharisees and the woman taking in adultery (John 8:2–11).

Together, then, the two scenes in this drawing tell a story found in John’s Gospel. Here, however, I have chosen to use their proximity to illustrate Christ’s teaching—and practising—of compassion, as described in Matthew 9:35–38. In the latter passage, we learn that Christ healed ‘every infirmity’ (v.35) of the people that he met. And infirmities may take many forms, moral as well as physical.

References

Konowitz, Ellen. 1997. ‘A “Creation of Eve” by Dirk Vellert’, Master Drawings, 35.1: 54–62

Guillermo Galindo :

Ropófono, 2013 , Wood, contact microphones, immigrants clothing

Robert Colescott :

Modern Day Miracles, 1988 , Acrylic on canvas

Dirk Vellert :

Christ Preaching in the Synagogue, with the Pharisees Bringing the Woman Taken in Adultery, c.1523 , Pen and brown ink, brush and grey ink; framing line in pen and brown ink, by the artist

A Call to Compassion

Comparative commentary by Ena Heller

The three works in this exhibition are separated by centuries and embody vastly different aesthetics.

One is a Northern Renaissance drawing made as a pattern for a stained-glass window, possibly part of a cycle that would visually translate the biblical narrative for the faithful.

Another is a twentieth-century painting by an African American artist intent on giving artistic expression to the plight of Black people in the United States.

The third is a twenty-first-century sonic sculpture created by a Mexican American artist documenting the immigration crisis at the US–Mexico border and giving voice to its unknown and often forgotten victims.

Only one of the three was created in the service and architectural context of the Christian Church. And yet all these works contain, explore, and comment upon the symbolism of the biblical passage considered in this exhibition. Intentionally or not, the three works embody the message resonant in Matthew 9:35–38. Considered together, they speak powerfully to notions of compassion and empathy.

In the Gospel passage, Jesus, as he preached in cities and villages, spread the message of compassion for the multitudes he encountered, showing a pathway to these ‘sheep without a shepherd’ (v.36). He saw them, and he empowered them. This is precisely what all the works in the exhibition do, albeit in different ways: pause to see the unseen, the unrecognized, the marginalized. And by being seen—acknowledged by the artists and by us as beholders—they are being empowered.

The drawing by Dirck Jacobsz. Vellert sets the stage by putting us in the space where Jesus is preaching in the synagogue. The crowded composition, with several other people witnessing the group in the foreground, looking on from different directions, indicates that the episode is not isolated, that Jesus’s preaching happened in many places and reached multitudes. And as Jesus saw the crowds, ‘he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless’ (v.36). He later embodied compassion in the way he treated the woman taken into adultery (John 8:2–11): having lost her way, she too had become ‘without a shepherd’.

A consistent feature of Jesus’s preaching is its concern to reach everyone with its message of redemption, whether by challenging them to change or by embracing them in their vulnerability. Here, he particularly acknowledges those who are in acute need, seeking to embrace them, and encouraging us to do the same. To feel compassion and to show mercy.

The same message of compassion is embedded in the other two works in the exhibition. Robert Colescott places a Jesus figure among Black people—a systemically marginalized people in twentieth-century America. It is not redemption, the artist tells us, that is not available to his people, but rather the everyday things necessary for survival, like electricity and food, access to health care and social networks. Seeing Black people well fed and well cared for, smiling in a carefree way, is the ‘miracle’ that Jesus is called upon to bring to countless Black communities in Colescott’s America. That they should need such a miracle is a biting criticism of the society they live in.

Compassion in today’s society—or more exactly the lack thereof—is also the theme of Guillermo Galindo’s sculpture, which abandons both narrative and figuration. The people for whom we are asked to show compassion are not depicted, their very absence a biting commentary. They cannot be depicted, the artist tells us, because we do not know who they are. We do not see them and cannot address them; the only witnesses of their passage through the border are the discarded clothing fragments that make up the sculpture. When activated—played as an instrument—the sculpture gives voice to those individuals, and encourages us to recognize their presence, to feel their pain, and to offer empathy and compassion. The fact that we do not know the names or stories of the multitudes who suffer should not prevent us from acknowledging them, from feeling for them and trying to help. This was, after all—as this passage affirms—central to the gospel preached by Jesus. And in the twenty-first century, it is this humanitarian call we should all heed.

Commentaries by Ena Heller