John 7:53–8:11

The Woman Caught in Adultery

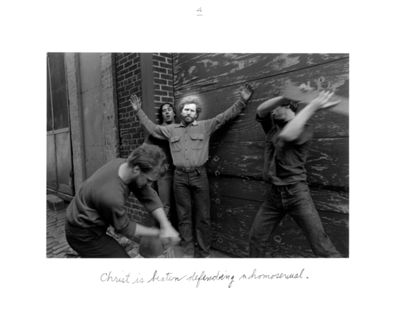

Duane Michals

No. 4: Christ is beaten defending a homosexual, from the series Christ in New York, 1982, Gelatin silver print and pencil on paper, 203.2 x 254 mm, The Portland Art Museum or Ackland Collection; Museum Purchase: Robert Hale Ellis Jr. Fund for the Blanche Eloise Day Ellis and Robert Hale Ellis Memorial Collection, 88.33A-F, ©️ Duane Michals, Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

The Teachers Caught in Hypocrisy

Commentary by Sheona Beaumont

Of the various visual media which have been used to recontextualize Bible stories and characters, photography offers a particularly direct connection with our modern world. Artists have recontextualized Christ through photography in a wide variety of ways, often choosing to appropriate him in order to comment on socio-political issues of the day.

In 1982, Duane Michals staged a series entitled Christ in New York, at a time when Christian conservativism in the U.S. was increasingly vociferous in defending traditional family values—opposing, among other things, abortions and homosexuality. Michals’s series shows a haloed man appearing in six scenes that include Christ sees a woman being attacked and Christ is shot by a mugger with a handgun and dies. In each, Michals included a pencilled caption: a description that emphasizes Christ’s relative passivity in the scenes.

It is a crafted narration of something like the Passion: things either happen in front of Jesus as detached observer, or they happen violently to him. Christ is beaten defending a homosexual in this sense conflates some of the foreboding events that happen either side of the woman’s judgement in John’s Gospel. The crowd wants to seize Jesus, the teachers of the law want him arrested (7:30, 32, 44), and this escalates to a near-tipping-point of tension when they pick up stones to stone him (8:59). He is the one under attack, under condemnation.

That Michals shows us this premature crucifixion as a moment of defence, however, is poignant in a number of ways. It brings us back to the text about the woman caught in adultery, and to the issue of what, or who, is defended and why. As a gay man, Michals’s Catholic upbringing led to his own experiences of condemnation, and he has acknowledged that this work came out of his anger towards the religious hypocrisy of the time. By putting Christ in the way of a man who is accused of being in sin, and representative of many others accused in this way, the defence is clear. Michals would have his Jesus intervene in the political-religious righteousness of the day, this time offering a physical protection that is at once simply human and divinely loving. It is sharply observed, with both wryness and pathos, bringing us face-to-face with Jesus’s sacrificial act of salvation.

References

Gottschalk, Karin. 2017 [2002]. ‘Duane Michals: Asking Questions Without Answers’, www.Untitled.net, available at https://creativityinnovationsuccess.wordpress.com/archive/duane-michals-asking-questions-without-answers/ [accessed 28 June 2022]

Mirlesse, Sabine. 2013. ‘Duane Michals by Sabine Mirlesse, 26 March 2013’, www.bombmagazine.org, available at https://bombmagazine.org/articles/duane-michals-1/ [accessed 28 June 2022]

Shqipe Kamberi

Bride, 2017, Mixed media on canvas, 60 x 60 cm, Collection of artist; ©️ Shqipe Kamberi, photo courtesy of Shqipe Kamberi

The Woman Who Suffers

Commentary by Sheona Beaumont

In John’s Gospel, it is the accused woman who is brought before Jesus, but not the man. The crime of adultery, according to Deuteronomy 22:22, demanded that both man and woman receive the death penalty. Such a stark punishment was, by Jesus’s time, forbidden under Roman law, and the woman’s accusers here knowingly draw Jesus into the question of whose authority he will respect.

The woman alone is charged. This (commentators speculate) suggests a set-up: the death penalty would have been carried out by witnesses to the crime—who would hurl the first stone—and for this to have happened the husband may have acted to frame his wife (Derrett 1963: 5; Beasley-Murray 1987: 146). Either way, the assumed moral superiority of the male teachers of the law assumes a gendered inequality, which allows them not merely to expose only the woman, but also to gamble her life in their preoccupation with trapping Jesus.

Many artists in recent times have been concerned to highlight the effects of traditional patriarchal societies on women, where today they are still silenced, suffer, and are even killed, at the hands of state-sanctioned misogyny. Shqipe Kamberi’s 2017 exhibition in Kosovo, Consciousness: Past and Present, consisted of mask-like plaster reliefs of a female face, often incorporating elements of traditional Albanian textiles. She focusses on the strict customs of the Kanun (laws which govern some parts of rural Albania and Kosovo) with respect to the duties of a wife. Her brides’ faces always have covered or closed eyes, and she has talked about the loss of rights and identity which women experience in this culture.

Female artists elsewhere in the world are working to expose yet more disturbing practices: Sheida Soleimani’s installations and Shamsia Hassani’s graffiti art address Sharia law and the stoning of women in Iran. Like them, Kamberi understands art to be a means of bringing visibility to her subjects. Although her works of art—with their contortions of folds and coverings—recall the aggression they have suffered, her brides nevertheless appear.

To Jesus, women appeared. As with the woman of Samaria (John 4), Jesus creates a space for an accused woman not just to be seen, not even just to be defended, but to be wholly liberated. We can pray that for suffering women in our world today, such freedom will be equally real and their appearing (through feminist art) just as powerfully transformative.

References

Beasley-Murray, George R. 1987. John, Word Biblical Commentary (Milton Keynes: Word Publishing), pp. 143–47

Derrett, J. D. M. 1963. ‘Law in the New Testament: The Story of the Woman Taken in Adultery’, New Testament Studies, 10.1: 1–26

Roger Wagner

Writing in the Dust, 2016, Oil on canvas, 33.02 x 15.24 cm, Auckland Castle Trust; ©️ Roger Wagner; Photo: Courtesy of the artist

The Space for Grace

Commentary by Sheona Beaumont

The beating of a swallow’s wings,

A stone jar poised as if to fall,

A fierce and unforgiving sun

That beats upon a whitewashed wallThat finds and tracks each human flaw

And reads the writing in the dust

Of broken hopes and powdered dreams

And love reclassified as lust.Where images of shameful death

Describe a life defined by blame,

The beatings of a swallow’s wings

Above a place of public shameAre like the barest breath of grace

That stir the unforgiving air:

That shift the gaze and lead the eye

Beyond the camera’s fatal stareTo where one writes within that dust

Of dry bones in a bone-dry place,

Of broken hopes and powdered dreams -

The unseen, unhoped, words of graceWhich free accuser and accused

Which spell out how our life begins;

A motion like a breath of grace:

The beating of a swallow’s wings.(‘Writing in the Dust: The Men Taken in Hypocrisy’ by Roger Wagner)

Roger Wagner’s painting, to which this poem is an accompaniment, sets the scene in a concrete arena, a bleak prison-like space characterized by an almost monochrome palette.

An earlier version of this painting, from 2013, has a warmer sandy-yellow tone in both ground and figures’ robes, as well as including the green of palm trees in the now-empty background sky.

Arena or prison: both are manmade institutions for judgement, the poverty and harshness of whose processes are foregrounded here. The latter is a corrective facility for criminals; the former a place of spectacle and public scrutiny whose shifting forms traverse both the ancient Roman circus and the ubiquitous screens of modern media. In this painting, phone and film cameras are held aloft alongside machine guns in a veritable shooting gallery along the bottom edge.

This hardened world is the one where the ‘breath of grace’ swoops in almost unnoticed in the figure of the swallow. A symbol in Renaissance painting of Christ’s resurrection, the swallow’s appearance in the spring in Europe was understood to herald new life. In a moment of unexpected appearing, Wagner’s swallow—on canvas and in verse—is a figure for grace. The surprise of its gratuitous appearance in a situation apparently without grace is like the interruption of historical time by a kairos, a moment charged with transformative possibility. Like the barest tufts of grass near Jesus’s finger, life irrepressibly stirs when condemnation stops.

Duane Michals :

No. 4: Christ is beaten defending a homosexual, from the series Christ in New York, 1982 , Gelatin silver print and pencil on paper

Shqipe Kamberi :

Bride, 2017 , Mixed media on canvas

Roger Wagner :

Writing in the Dust, 2016 , Oil on canvas

Then Neither Do I Condemn You

Comparative commentary by Sheona Beaumont

The story of the woman caught in adultery is a startling and beautiful demonstration of Jesus’s upturning grace. Between ‘if any one of you is without sin, let him be the first to throw a stone’ (8:7), and ‘then neither do I condemn you’ (8:11), a world changes. A world set on laws of stone is replaced by a world created through actions of love. As one commentator has said of the episode, ‘the point is not the condemnation of sin but the calling of sinners: not a doctrine but an event’ (Schnackenburg 1980: 168).

In this sense, the event stands out distinctly, much as other events stand out in John’s Gospel like bright jewels. It can be helpful to think of it like this because, in fact, this episode did not belong in the earliest manuscripts we have of John. Some manuscripts include it in Luke’s Gospel, others exclude it altogether. And indeed, if we read sequentially from John 7 through to the end of John 8, it feels like a narrative disjunction: Jesus’s lengthy and involved exchanges with the crowd and teachers there offer a stark contrast to this episode, where he prefers evasion and silence.

Nevertheless, we can ask whether the way this passage strikes the reader—our intuition of its distinct or ‘separate’ quality—may be very much a part of John’s gospel message. The salvation Jesus brings is not found in the script of condemnation (John 3:17), but enters into history in his being, and in the distinct actions of his person. Jesus does indeed duck out of the religious teachers’ trap. In Roger Wagner’s painting—where either an intellectual or violent breakout seems to be the only choice (and the dramatic ‘setpiece’ for the watching media)—we see that Jesus has ducked out of shot and writes in the dust. Like silence in airtime, it is uncomfortable ‘dead air’, a step sideways from the expected narrative.

How the artists in this exhibition convey such a step sideways is part of the gift of visual commentary. They introduce their own take on the way Jesus ‘breaks frame’ with reality, rather as poetic or painterly intuition can take flight where the formal procedures of reason get stuck. Wagner’s palette often signifies this shift through its alternative spectrum of cooler tones, giving an effect of light altered in some way—whether artificially or perhaps like bleached moonlight. The world is seen differently.

Duane Michals transposes a modern-day Christ into the photographed reality of New York. In the history of modern art, this could be just another appropriation of the Bible—a cool stylistic choice—but in fact his is a personal and serious wrestling with the searing heat of the 1980s culture wars, and in particular, the condemnation of homosexuality by church leaders in the U.S.

Michals, like Wagner, has the Bible make a journey, placing it into a new visual scenario. In such transposed spaces, the effect of liberation from other closed, limiting judgements of the human condition is greatly illuminated. In Christ is beaten defending a homosexual, the unassuming, ordinary, human figure of Jesus is a foil to expose those whose violent expressions of religious righteousness are made in his name. The compounded imagery of his back-street crucifixion is not without irony. As Jesus steps right into the path of this condemnation, he figures the sacrifice he makes for all humankind.

This kind of space for questioning reverberates just as loudly when an artist’s representation seems to reflect the text unintentionally. Shqipe Kamberi’s Bride is a consideration of the rights of women in marriage as held in Albania today. The suppression of identity, of voice, of participation in society and the home is legitimised by the religious customs of the Kanun. Kamberi’s is a practice that insists that we see this; that we truly see it. Women are silenced, often receiving no public defence in cases of adultery, and in some parts of the world even still executed as a result of male advantage.

In bringing Kamberi’s work into conversation with John’s Gospel, Jesus’s actions become more clearly about seeing her, the woman. And in the end here, her restoration and liberation are fundamentally completed by unconditional love, the kind that only God can bring. The equality that our world urgently longs for—across issues of sexuality, gender, race, wealth, and more—is deeply felt. But if our words on these subjects are not to be just another ‘clanging cymbal’ (1 Corinthians 13)—a court of public shame and judgement—we need to meet Jesus when everyone else has gone. The quiet place where he straightens up to look us in the eye, and sets us free.

References

Schnackenburg, R. 1980. The Gospel According to St. John, vol. 2 (London: Burns & Oates)

Commentaries by Sheona Beaumont