John 4:1–42

The Woman at the Well

Lavinia Fontana

Christ and the Samaritan Woman, 1607, Oil on canvas, 161 x 120 cm, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte; Q 623; 84087 S; de Rinaldis 1911 n. 239, Courtesy of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e del Turismo – Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte

A Pioneer Empowered

Commentary by Elizabeth Lev

Often described as the first professional female artist in Italy (Murphy 2003: 30), Lavinia Fontana may have felt a special affinity for this subject. The Samaritan woman was a pioneer of sorts—the first to announce Christ to her people—and Fontana, as the only woman in Europe then painting altarpieces, had just joined the elite rank of painters who, in the words of Archbishop Gabriele Paleotti, were ‘tacit preachers to the people’ (Paleotti 2012: 301).

Twenty-six years earlier, her Noli me Tangere, showing Mary Magdalene as the first person to encounter the resurrected Christ, had catapulted her to success; now, famous throughout Europe, Fontana turned to another woman who was crucial to the message of universal salvation.

A seated Jesus rests his head on his palm while gazing up at the woman. He is fully absorbed in their conversation. She appears to be his whole world at this moment: one soul claiming his full attention. He gestures gently with an open hand, offering, not ordering. This kindness seems to startle her. Her brows rise, her fingers splay in surprise. Her head inclines towards Jesus as if drawn by the magnetic force of his promise, ‘the water that I will give will become in them a spring of water gushing up to eternal life’ (John 4:14 NRSV).

Fontana accentuates the woman’s desirability. After decades of painting portraits of Bolognese noblewomen, the artist was expert at depicting fine materials and flattering clothes. The woman’s hair is elaborately dressed, her figure highlighted by the red band under her breasts and the belt cinching her waist. There is a flash of leg under the gauzy skirt. Little surprise that the apostles, discernible in the distance at the left, look taken aback. Why is the Master alone with a beautiful but forbidden woman (‘For Jews have no dealings with Samaritans’; John 4:9)?

It may be that Fontana, a married woman with eleven children, who had played by all the rules of her society to attain her position, felt compassion towards this more vulnerable ‘outsider’—much as Jesus did. A rope tied around the handle of the jug falls to the ground between the two. It is symbol of penitence, often worn around the neck in pious confraternities as a sign of the repentant sinner.

Despite her irregular personal life, the waters of eternal life will renew the Samaritan woman, preparing her to be a herald of Christ.

References

Murphy, Caroline P. 2003. Lavinia Fontana: A Painter and Her Patrons in Sixteenth-Century Bologna (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Paleotti, Gabriele. 2012. Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images, trans. by William McCuaig (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute)

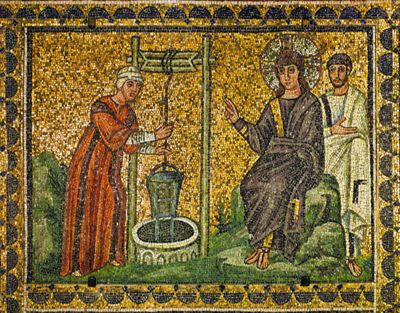

Unknown artist

Christ and the Samaritan Woman, 6th century, Mosaic, Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna; Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

A Witness Summoned

Commentary by Elizabeth Lev

Part of the mosaic scheme in nave of the sixth-century Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, this is one of thirteen New Testament episodes depicted in the uppermost band of the north wall. It stands out because of the vivid colour of the woman’s robe. Jesus is draped in dark purple while most of the other figures in the series wear white togas. The Samaritan woman, by contrast, is cloaked in fiery orange. She shares this notable brightness with a seraph four panels away—a thought-provoking choice. It may signify her role as a messenger to her people, an angelos to the Samaritans.

To render the work visually effective from a distance (it is positioned high up on the wall of the nave) the artist has reduced the scene to just three figures: Jesus, the woman, and an apostle. The well at the centre of this composition is described in the biblical text but may here also represent baptism, the sacrament par excellence of the early Church (Grabar 1968: 222).

Sixth-century notions of decorum required that the woman’s hair and body be well-covered, but this in no way diminishes her gracefulness. By bending to draw up the water she seems almost to bow to Jesus, yet the purple stripes of her dress mirror the kingly violet of his tunic. These marks of nobility in the woman’s garb are perhaps intended to exalt her role: she will soon lead her people to the Saviour.

The apostle does not seem surprised by Jesus’s conversation with the woman, despite what the text recounts (John 4:27). Instead, he points calmly in the direction of the high altar of the church, while gazing, like Jesus himself, towards the viewer. He straddles two dimensions, that of the narrative and that of viewer, directing the beholder’s attention (as John’s Gospel does) from the historical event to the eternal truths of faith.

Despite her ‘five husbands’ and present presumed lover, the woman was chosen for a personal revelation on the part of God-made-man. Like many he met, her encounter with Christ is intimate: during their exchange he reveals the private details of her life and the needs of her soul. The mosaic’s lack of extraneous detail emphasizes this intimacy.

She, as a result, will return to her town proclaiming him—becoming a bridge to reconcile her Samaritan people with the Jews by bringing them face to face with the Messiah himself.

References

Grabar, André. 1968. Christian Iconography: A Study of its Origins (Princeton: Princeton University Press)

Wilpert, Joseph. 1932. I Sarcofagi christiani antichi, vol 1., Monumenti dell'antichità cristiana, pubblicati per cura del Pontificio istituto di archeologia cristiana

Diego Rivera

The Woman at the Well, 1913, Oil on canvas, 145 x 125 cm, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City; © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo: Courtesy of Museo Nacionlal De Arte, Mexico City

A Worker Unfettered

Commentary by Elizabeth Lev

Diego Rivera and religion parted ways early on, but the influences of Christianity on this Mexican artist's work were powerful. After a strict Catholic schooling, the budding painter enrolled in the San Carlos Academy at the age of 12. There, he was taught by Santiago Rebull, a painter shaped by the ideals of the devout brotherhood of painters in Rome known as the Nazarenes. Later, in Spain, Rivera would be further inspired by the religious art of El Greco. His youthful formation was steeped in an art of sacred narrative and expression.

From Spain Rivera went to Paris, and befriended Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, and other painters at the vanguard of an art unfettered by religion. He became intrigued by the new, daring style of Cubism.

The Woman at the Well was painted in Paris in 1913, and Cubism’s multi-faceted perspectives seem well suited to Rivera’s exploration of the conflicts between his past and his present.

The work might best be interpreted as adapting a biblical subject for a secular context. Perhaps it is an expression of solidarity. Though far from the fields of Mexico, and enjoying the very cosmopolitan artistic circles of Montparnasse, Rivera felt a strong sense of national identity, which drew him back to familiar imagery from home even in the midst of his innovative artistic experiments. Moreover, he was imbibing Marxist teaching, and was aware of the Communist movement’s celebration of women as workers. He painted The Woman at the Well in the same year that he produced The Adoration of the Virgin (another of his few overtly religious subjects) in which he depicted Mary with the appearance of a Mexican peasant woman. In The Woman at the Well, likewise, the large blocks of the woman’s arm and leg suggest the sturdy solidity of a country worker.

The woman is clearly defined amid the disrupted planes of Rivera’s painting: the furrowed brow, the rose sleeve, the curve of grey to form her hip. Jesus, however, is almost indistinguishable amid the jumbled shapes and symbols. A spray of brown at the upper left of the composition may suggest hair, but no face is visible. Instead we see an orb with a bright bird to the left of it—perhaps a phoenix (an ancient symbol of resurrection). If Jesus is there, he is revealed only to the woman, not yet to the viewer.

Lavinia Fontana :

Christ and the Samaritan Woman, 1607 , Oil on canvas

Unknown artist :

Christ and the Samaritan Woman, 6th century , Mosaic

Diego Rivera :

The Woman at the Well, 1913 , Oil on canvas

A Grand Plan for Woman

Comparative commentary by Elizabeth Lev

Only John’s Gospel tells the story of the woman at the well. It is one of three momentous conversations that Jesus has with women in this Gospel. He first reveals himself as the Messiah to the Samaritan woman. A few chapters later he tells Martha, ‘I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live’ (John 11:25 NRSV). Then he appears, resurrected, to Mary Magdalene, telling her to go and share the news: ‘Do not hold on to me, because I have not yet ascended to the Father. But go to my brothers and say to them, “I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God’” (John 20:17 NRSV).

John was the disciple who would be entrusted to care for the Mother of God (John 19:26–27). The Gospel that bears his name seems to perceive a grand plan for women in God’s design.

The encounter with the woman at the well is one of Jesus’s numerous unexpected interactions, in which he catches not only his interlocutor but his disciples, and his contemporary society, off guard. He becomes a bridge of healing across peoples (for the Samaritans and the Jews had no dealings with each other), between men and women (for his frank and forward conversation with the woman), and between God and sinners (in that Jesus does not shun her on account of what would have been regarded by many of her contemporaries as her sinful state of life).

All three artists in this exhibition chose to focus their attention closely on Jesus and the woman, reflecting the intense intimacy of their dialogue. The disciples are reduced to one, two, or none, and they do not distract from the momentous encounter.

In each artwork there is an emphasis on the importance of the woman that parallels that in the text. The Ravenna mosaic achieves this through the use of vivid colour; Lavinia Fontana’s painting through the woman’s eye-catching finery and her dominant position as she looks down at Jesus from above; and Diego Rivera through his use of bold curving lines to bestow figurative definition on her amid the dislocations and abstraction of the composition as a whole.

Jesus’s treatment of women has been a source of inspiration for artists for centuries: the numerous early depictions of the woman with the issue of blood, the myriad Noli Me Tangeres in which Mary Magdalene is made apostle to the apostles and, of course, the woman at the well, who—though a very rare subject in the Christian funerary art of the pre-Constantinian period (Wilpert 1932: 306)—would be reproduced countless times in the centuries that followed. The Samaritan woman’s appearance may change—modest, bold, or sensual—but she is always a forceful presence in the work.

In the Ravenna mosaic, Jesus gestures with his right hand towards the woman. In early Christian chironomia (the rhetorical art of hand gesture) the movement is charged with symbolism, signifying speech and / or blessing. It suggests Jesus’s transformative revelation to the woman as she asks about the Messiah—‘I am he,[a] the one who is speaking to you’ (John 4:26 NRSV)—but perhaps also his commissioning of her. The woman, her sins forgiven, is being given a mandate to bring others to Christ. She is being made an evangelist.

Fontana’s work highlights the redemptive element of the story, alongside the surprise of Jesus’s respectful engagement with this woman. Jesus confronts her with the messy truth of her life (John 4:18), but nonetheless calls her to service. Her encounter with Christ changes her life, her past no longer defines her, and now she may go forward to bring others to Christ.

Rivera’s fractured image effectively reflects the modern era, struggling to relate past and present, and divided between beliefs and ideas. The sensuality of his use of line speaks to our age of desires, while the Samaritan woman’s earthenware jug signals the burden of work on the world’s poor. The work’s superimposed shapes and lines seem to evoke the chaotic currents of modern life.

In this context, the hiddenness of Christ may perhaps signal the receding of religion in the public square. Nevertheless, his presence is suggested. He does not impose an objective order on the tumult of the work. Yet, towards the left of the composition, and balancing the figure of the woman, we can discern an upside-down scythe. It is as though the symbol of death has been overturned by living water. The water of the well is green as are the swirls around the base of the canvas; it is the colour of new life. Less a story of evangelizing mission, this work speaks to the hope for universal liberation, moving beyond the confines of people of faith to all those who labour and toil.

Commentaries by Elizabeth Lev