Matthew 14:1–12; Mark 6:14–29; Luke 9:7–9

The Beheading of the Baptist

Works of art by Giovanni di Paolo, Nalini Malani and Unknown artist, Southern Netherlands [?]

Unknown artist, Southern Netherlands [?]

Head of John the Baptist, c.1500–60, Alabaster, 26.7 x 21 cm, The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Purchased with the support of the Rijksmuseum Funds, BK-1998-1, Courtesy of Rijksmuseum

Flesh Becomes Stone

Commentary by Imogen Tedbury

During the Fourth Crusade, what was believed to be the skull of St John the Baptist was discovered in Constantinople, whence it was removed and given to Amiens Cathedral. Relics of St John’s head—and there were other contenders across Europe—were considered responsible for miraculous cures.

Numerous sculpted heads survive in addition to these relics. This one is missing its charger, probably made from a different material such as metal, wood, stone, or majolica, which would have emphasized the synergies between flesh-like alabaster and stone-like flesh. Alabaster was widely used for sepulchral monuments across northern Europe. It is softer than marble, allowing for a pliancy that is not achieved with harder stones.

Here, St John’s face is highly polished, emphasising the softness of his fluttering eyelids and parted lips. Mottled flaws in the stone run across the saint’s cheekbones, and these textural veins seem to have inspired the dimensions of his features. Underneath John’s head, where hair blurs into the unfinished, unseen surface, marks suggest that some of this carving was done with a toothed gouge. Drill marks are visible deep in the curls of his hair and elsewhere.

In some ways this head is a portable object, but it is also impractically heavy at 13.4kg. It is unknown whether these objects were intended to be venerated on an altar, in another liturgical context, or in the realm of private devotion. According to the York Breviary (late fifteenth century), ‘Johannes in disco’ (as these sculptures were known) also symbolized the Eucharist, ‘the body of Christ which feeds us on the holy altar’. As bread becomes flesh in the Mass, so here flesh becomes stone.

References

Belyea, Thomas. 1999. ‘Johannes ex disco: Remarks on a Late Gothic Alabaster Head of St. John the Baptist’, Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum, 47.2: 100–117

Baert, Barbara. 2019. ‘The Spinning head. Round forms and the Phenomenon of the Johannesschüssel’, in Runde Formationen. Mediale Aspekte des Zirkulären, ed. by Joseph Imorde and Andreas Zeising (Siegen: Siegen University Press), pp.45–58

Nalini Malani

Can You Hear Me?, 2020, Animation Chamber, 9 channel installation with 88 single channel stop motion animations, sound; ©️ Nalini Malani; Photo: Ranabir Das

When Can I Fight?

Commentary by Imogen Tedbury

[H]is head was brought on a platter and given to the girl, and she brought it to her mother. (Matthew, 14:11)

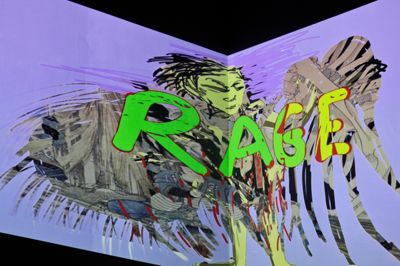

Can You Hear Me? takes as its departure the abduction, rape, and brutal murder of Asifa Bano, an eight-year-old Muslim girl, whose body was defiled as a symbol of patriotism by a group of Hindu men in the region of Jammu and Kashmir in 2018.

In what Nalini Malani calls the Animation Chamber at the Whitechapel Gallery, eighty-eight hand-drawn iPad clips are projected onto exposed brick walls. These drawings were made over the course of three years, and they embody thoughts and fantasies in animated journal entries.

Literature, history, current affairs, and memory are enacted through this ‘moving graffiti’ (Butler 2020: 61). Quotations from Adrienne Rich, Samuel Beckett, Berthold Brecht, James Baldwin, and others flicker amongst illustrations of ancient mythology, personal experience, and the everyday news cycle. The prophetess Cassandra, Radha the Hindu goddess of love, and Lewis Carroll’s Alice jostle for space with violent men, engorged and angry. Alice is an avatar for Asifa, the murdered little girl, who skips, screams, shrinks, shape-shifts, seeks answers. ‘Can you hear me?’ she asks. Like St John the Baptist, Asifa is a ‘vox clamantis’, a voice of testimony and judgment after her death.

There is a force to these images and texts, in their repetition, their colour. ‘Battling with myself’—‘I am confined to my head’—‘when can I fight’—‘and so his eyes were out, no guilt, no blame’—‘REVENGE’. The fragments voice the guilt-ridden anticipation of violent vengeance: perhaps like that of Herodias, anxiously waiting for her daughter to bring in St John the Baptist’s head on a platter (Matthew 14:11). Malani’s work confronts ‘the absurd decisions made by the powers around us [that] lead to the most dangerous and horrific ends’ (Malani 2020: 74).

Yet text and image here are ultimately an alternative to vengeance. Their creation, presence, and transformation act as a ‘deterrent’ to action. Underlining this inaction is the manner in which each projection ends, with the screaming face of Medea, desperate protagonist of Greek tragedy, a woman pushed to her limits.

References

Instagram.com/nalinimalani

Butler, Emily. 2020. ‘How Can We Listen Better?’, in Nalini Malani: Can You Hear Me? ed. by Emily Butler, Inês Costa, and Johan Pijnappel (London: Whitechapel Gallery), pp. 61–68

Malani, Nalini. 2020. Domus India, 9.3: 64–75

Giovanni di Paolo

The Head of Saint John the Baptist Brought before Herod, 1455/60, Tempera on panel, 68.5 x 40.2 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago; Mr and Mrs Martin A. Ryerson Collection, 1933.1015, Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago

Halo and Platter

Commentary by Imogen Tedbury

In this gaudy and gory scene, Giovanni di Paolo presents Matthew 14:11–12 as a moment of reckoning for Herod. Confronted with St John’s head on its golden platter, he throws up his hands, the whites of his eyes visible in his slack-jawed horror. This is the ghastly vision that Herod immediately recalls when he hears about Christ’s miracles. ‘John, whom I beheaded, has been raised from the dead!’ he exclaims (Mark 6:16). ‘John I beheaded’, he remembers (Luke 9:9). How could he forget?

This painting is one of twelve panels detailing scenes from the life of St John the Baptist, which probably once formed doors encasing a sculpture or relic of the saint in Siena Cathedral—perhaps the Baptist’s arm, presented in 1464. The paintings may have been commissioned by a lay confraternity who gave succour to condemned criminals, the Compagnia di San Giovanni della Morte. Several scenes, including this one of Herod’s feast, borrow their composition from Donatello’s bronze reliefs for Siena’s baptismal font (c.1417).

As a group, the panels dwell on the Baptist’s arrest, imprisonment, and execution with great theatricality. ‘Sets’ are repeated across different scenes: a rocky desert, a prison, a banqueting hall. A repeating cast of servants proffer platters as they weave through pillars and doorways. Gilded dishes, laid on the banquet table or held by hand, echo the ultimate salver containing the Baptist’s head, which appears twice in this final scene of the tragedy. His head is silhouetted against his golden halo—or is it a golden lid held by the executioner to mock his headless victim? Treatment of halo and platter is disconcertingly consistent. As the painting’s gold leaf has worn away over time, the red bole used to adhere it to the panel has begun to shine through, giving a bloody stain to golden tableware.

References

Gordon, Dillian. 2003. National Gallery Catalogues: Italian Paintings, The Fifteenth Century (London: National Gallery), nos. 5451–54, pp. 98–99

Brandon Strehlke, Carl. 1988. Painting in Renaissance Siena, 1420–1500 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), p. 216, fig. 1

Unknown artist, Southern Netherlands [?] :

Head of John the Baptist, c.1500–60 , Alabaster

Nalini Malani :

Can You Hear Me?, 2020 , Animation Chamber, 9 channel installation with 88 single channel stop motion animations, sound

Giovanni di Paolo :

The Head of Saint John the Baptist Brought before Herod, 1455/60 , Tempera on panel

Bodily Substitutions

Comparative commentary by Imogen Tedbury

Framed within a broader narrative of Christ’s miracles, the account of John the Baptist’s death is distinctive in being presented as a memory. Specifically, it is a memory of Herod’s.

It’s a case of mistaken identity. Reports of Christ’s works have reached the king; it is rumoured that he is a prophet—Elijah perhaps. But such is Herod’s fear and his guilt that he assumes the worst of these rumours:

‘John, whom I beheaded, has been raised’. (Mark 6:16)

‘This is John the Baptist: he has been raised from the dead’. (Matthew 14:2)

Herod is not the only one to confuse the cousins: other people had wondered whether John might be the Messiah (Luke 3:15). In his actions, life, and death, John prefigures Christ. John’s decapitated head, contained in its vessel, prefigures the Eucharist, or Christ’s body in its tomb. Herod’s fears of John’s resurrection prefigure Christ’s resurrection.

Even Luke’s less credulous Herod cannot shake this gruesome vision of the preacher he once admired: ‘John I beheaded; but who is this about whom I hear such things?’ (Luke 9:9). Herod’s memory prompts Matthew and Mark to tell us the grisly backstory, recalling John’s last days. From them, we learn that John died at the request of two women, mother and daughter. They do not give the order themselves, nor do they strike the blow, as the Israelite hero Judith once wielded her sword (Judith 13:8). Matthew tells us that John’s ‘head was brought on a platter and given to the girl, and she brought it to her mother’ (Matthew 14:11). But Herodias and Salome are compromised by their role in John’s death, by the violence of their intentions. This is attested by common confusions between Salome and Judith that occur in visual representations of these strong women, such as the National Gallery’s 1510 painting by Sebastiano del Piombo, currently titled Judith (or Salome?).

Mistaken identity and bodily substitution thread throughout these passages. They begin with John’s criticism of a substitution: that of Herod taking his brother Philip’s wife, replacing his brother in Herodias’s bed. Herodias desires John’s death but she does not ask for this herself; instead it is her daughter who asks in her place. John’s head, presented on a platter at Herod’s birthday banquet, becomes another delicacy at the feast. Giovanni di Paolo takes such substitutions as his theme: servants have doubles, plates echo haloes, hallways become labyrinths. In his painting, Salome watches from a distance, a jaunty kick echoing her earlier dance, replacing Herodias, who is absent.

The sculpted head of John the Baptist is another replicated, substituted object. Multiple sculpted heads, evoking multiple venerated skull relics, embody Herod’s memory of this ghastly tableau, framed by their platters. Without its frame, however, this sculpted head is activated, caught between the moment of execution and the moment it is rested on its platter, to be presented to Salome, who will in turn bring it to Herodias.

What are these women’s motives? We are told Herodias bears a grudge against John, who has called her marriage lawless. Later retellings—by Oscar Wilde or Richard Strauss or Gustave Flaubert—interpret John’s death as an act of revenge in response to thwarted desire: Herod’s for Salome; Salome’s for John. Nalini Malani takes this idea further, exploring how the powerful lash out against perceived threats to their agency, whether in the violence of a state against its people or eight men against one little girl. ‘Watch out!’ says one of Malani’s angry faces, pointing a menacing finger.

Yet for Herodias, this threat is real. Despite her status, John’s condemnation of her marriage risks her and her daughter’s safety. No wonder she fears him and desires his death, choosing to take what action she can. As one of Malani’s women says, via Maya Angelou, ‘Life’s a bitch. You’ve gotta go out and kick ass’. ‘This is not an axe till it performs’, Malani adds, an ominous annotation to a heavy-handled weapon, before a screaming face and amputated limbs appear as blood-red linear additions.

John cannot be silenced, however. As a prophet, a mouthpiece of God, he reasserts his voice even in death. His voice is his legacy. Meanwhile, Herodias’s furious self-defence consigns her to historical memory as a second Jezebel, another prophet-killing queen (1 Kings 18:4). But is this vengeance or self-defence? Like Malani’s Medea—screaming, exhausted—Herodias is pushed to her limits, pushed to violent action. Other women remain silent. Can you hear them?

![Head of John the Baptist by Unknown artist, Southern Netherlands [?]](https://images-live.thevcs.org/iiif/2/AW0999_Unknown+artist+Southern+Netherlands_Head+of+John+the+Baptist_RIJK.ptif/full/!400,396/0/default.jpg)

Commentaries by Imogen Tedbury