Additions to the Book of Daniel: Susanna

Susanna and the Elders

Artemisia Gentileschi

Susanna and the Elders, c.1610, Oil on canvas, 170 x 119 cm, Schloss Weißenstein, Pommersfelden; Schloss Weissenstein, Pommersfelden / Akg-images / Album / Fine Art Images

Susanna and Gentileschi Exposed

Commentary by Samantha Baskind

The elders are in the midst of propositioning Susanna, whispering in her ear; the fingers of the elder on the left may even be brushing against Susanna’s hair. Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi paints a grimacing Susanna awkwardly turning her head and corkscrewing her body away from the lurking judges, in obvious discomfort and repulsion. The elders have violated her privacy and she has been cornered. The spare background keeps the viewer’s attention focused on the interaction between Susanna and her oppressors, and emphasizes the sense of entrapment. So does the placement of the figures close to the front of the composition.

Artemisia was an outlier in her time both for being a female artist and for what some believe were her motivations for painting this apocryphal tale.

The daughter of a well-known artist, Orazio Gentileschi, she trained with her father during a period when female artists were almost always excluded from the field, save in unique circumstances. For some male artists, the story afforded an opportunity to paint a nude or half-nude woman. Typical renditions of Susanna by Italian artists of the earlier generation, such as Tintoretto (1555–56), do not show Susanna as a victim or parse the psychological ramifications of her encounter with the elders. Rather, these artists’ interpretations of the narrative, and most others from a male hand, revel in flesh and the female body.

Artemisia appears to have had other provocations. She endured sexual harassment and then, at nineteen years old, was raped by an artist her father had hired to teach her perspective. Some scholars believe that her sensitivity to the subject of Susanna and the Elders, which she painted four times and (by all evidence) of her own volition, came from a personal place. For Artemisia, Susanna’s plight needed to engender empathy in the viewer, and her presentation of Joachim’s unfairly threatened and maligned wife conveys the agony endemic to her predicament.

References

Christiansen, Keith. 2004. ‘Becoming Artemisia: Afterthoughts on the Gentileschi Exhibition’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, 39: 101–26

Garrard, Mary D. 1982. ‘Artemisia and Susanna’, in Feminism and Art History: Questioning the Litany, ed. by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: Harper and Row), pp. 146–71

Locker, Jesse. 2015. Artemisia Gentileschi: The Language of Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Unknown Carolingian artist

The Lothair Crystal, Crystal: c.848; Fitting: 15th century, Rock crystal, gold, copper, 183 x 13 mm, The British Museum, London; 1855,1201.5, © The Trustees of the British Museum / Art Resource, NY

Susanna in Sequence

Commentary by Samantha Baskind

This unusual object does not confine the story to the lecherous encounter with the elders and does not even depict a nude Susanna at her bath. Rather, in a lively style, this tiny, Carolingian engraved rock crystal portrays a longer span of the biblical narrative—eight episodes in all.

Read clockwise, the first scene shows the elders propositioning Susanna, who stands clothed in an enclosed space carrying two vessels. But this pivotal moment is followed by various others, moving from the elders’ false accusation of Susanna to their cross-examination by Daniel to their violent death by stoning. The central scene has the prophet Daniel sitting on a throne of judgement conferring his wise decree of innocence, answering the virtuous Susanna’s prayers to heaven (as suggested by her upraised arms). The gemstone is inscribed with short Latin inscriptions from the Vulgate Bible to aid the viewer’s understanding of the actions of its forty-one figures, and recalls manuscript illuminations of the period (e.g. Utrecht Psalter).

A Latin inscription above the central scene indicates that the medieval medallion, with a copper gilt frame added in the fifteenth century, was designed for Lothair II, King of the Franks. Exactly why the story of Susanna was represented remains a matter of debate, but two interpretations predominate in the associated literature.

The first draws a connection between the biblical Daniel’s wise judgement and that of the royal Lothair’s judiciousness.

Less obviously, it has been hypothesized that the biblical story may have been deployed as a response to problems in Lothair’s marriage. Unable to produce an heir, Lothair had accused his wife Theutberga of incest in an effort to divorce her and marry his mistress, with whom he had illegitimate children. The pope denied the divorce. So perhaps Lothair offered the crystal to his wife as a gift of contrition and a gesture of reconciliation—the carefully chosen iconography on the gem meant as an acknowledgement of the false charges he had brought against her, and a public demonstration of her innocence.

References

Flint, Valerie I. J. 1995. ‘Susanna and the Lothar Crystal: A Liturgical Perspective’, Early Medieval Europe, 4.1: 61–86

Kornbluth, Genevra. 1995. Engraved Gems of the Carolingian Empire (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press)

Thomas Hart Benton

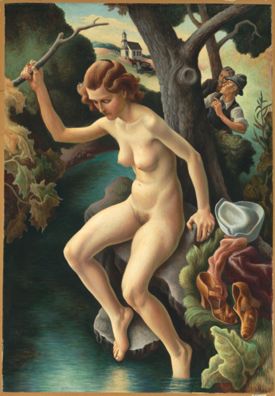

Susanna and the Elders, 1938, Oil and tempera on canvas, mounted on panel, 152.4 x 106.7 cm, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; 1940.104, © 2019 T.H. and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Susanna in Modern Missouri

Commentary by Samantha Baskind

Thomas Hart Benton, especially known for his pictures of American subjects in the period between the World Wars, subverted nearly every artistic norm in his modern portrayal of Susanna and the Elders. As Benton pictures the episode, a contemporary Susanna dips her toes into a stream in rural Missouri, the locale featured in many paintings by the Missouri-born-and-bred painter. Muscular and lithe, this erotic Susanna wears vibrant red nail polish, has coiffed hair pinned up with a barrette, and is replete with pubic hair, a shocking inclusion in paintings of nudes, biblical or otherwise, in the history of Western art. Susanna’s dress, cloche hat, and stylish high-heels sit on the grass next to her, conspicuously discarded, further underscoring her nudity.

Two men in contemporary clothing peer at the unsuspecting Susanna from behind a tree, trying to get a better view; the man farthest away wears a moustache and strongly resembles Benton. In the distance, a church, mules, and Model T Ford are visible. The church offers a stark contrast to the decidedly profane actions of the Peeping Toms, and as such the painting has been interpreted as a critique of religious hypocrisy.

At a 1939 exhibition in the City Art Museum of St Louis the painting garnered much controversy. One viewer derisively called this modern, sexualized rendition, ‘Lewd, immoral, obscene, lascivious, degrading, an insult to womanhood, and the lowest expression of pure filth’ (quoted in Adams 1989: 290). As Benton recalled in his autobiography, at that same exhibition a rope stanchion had to be placed before the painting because so many men came to ogle the nude Susanna (Benton 1968: 28).

Without the title, the subject of the work would have been almost impossible to recognize because of its departure from traditional representations of Susanna and the relative lack of biblical art in America. The strain of Puritanism in America after the birth of the country discouraged a religious art, preferring the verbal as a means to communicate ideas about God. A few nineteenth-century artists attempted an occasional biblical theme, but America’s taste for biblical subjects was rare.

Without a heritage of religious iconography, most twentieth-century American artists also ignored the Bible as a source. Benton, one of a small number of interwar American artists to paint biblical subjects, gives attention to this subject from the Apocrypha in an original and subversive fashion.

References

Adams, Henry. 1989. Thomas Hart Benton: An American Original (New York: Alfred A. Knopf)

Benton, Thomas Hart. 1968. An Artist in America. Third edn. (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press)

Burgard, Timothy Anglin, et al. 2005. ‘The Naked Truth’, in Masterworks of American Painting at the De Young (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), pp. 357–61

Artemisia Gentileschi :

Susanna and the Elders, c.1610 , Oil on canvas

Unknown Carolingian artist :

The Lothair Crystal, Crystal: c.848; Fitting: 15th century , Rock crystal, gold, copper

Thomas Hart Benton :

Susanna and the Elders, 1938 , Oil and tempera on canvas, mounted on panel

Vulnerability, Vindication, and Voyeurism

Comparative commentary by Samantha Baskind

The story is a familiar one with a terrible conundrum: Joachim’s beautiful and righteous wife Susanna innocently bathes alone in her garden when confronted by two eavesdropping, lecherous elders who desire her. These so-called exemplars of the community proposition and threaten Susanna: she must have sex with them or they will falsely accuse her of adultery. Susanna finds herself between a rock and a hard place, knowing that if she acquiesces then she will break a commandment and be killed for her transgression, while if she does not submit then (even though she will at least have remained faithful to the commandments) she will also be killed. The Greek Septuagint’s additions to the book of Daniel relays this salacious biblical soap opera, one of slander, sexual titillation, and blackmail. In the end, the heroine/damsel in distress Susanna preserves her purity when she stands her ground, providing an exemplar for her people. The hero Daniel swoops in and intervenes, tenders vindication, and decrees fatal punishment on the villains.

The three works of art exhibited here, from distinct geographical spaces and periods of time, offer conspicuously divergent approaches to this rich account. The unknown artist who designed the Lothair Crystal was commissioned to create a work of art either to further the reputation of a king in the eyes of his subjects or to exculpate the king’s wife. Daniel’s wisdom and Susanna’s faith take precedence in this early representation, which attempts to show various facets and nuances of the story in a continuous narrative. The Lothair Crystal avoids all nudity and salaciousness by virtue of its commissioned goals as well as the artistic conventions and moral code of its time.

Like a majority of artists before her, Artemisia Gentileschi invites her viewer to focus on the specific moment in the garden when a pious Susanna is accosted by the prurient elders. Yet no verdant garden scene is depicted in Artemisia’s painting, nor is Susanna a sensual, voluptuous nude unaware that two men are spying on her. In her distinctly original interpretation, Artemisia intensifies our awareness of Susanna’s distress. Her Susanna expresses the emotions of a frightened woman under siege in an unprecedentedly acute way.

Thomas Hart Benton treats the theme very differently in his erogenous canvas—following no prototype. He paints a Susanna who, though oblivious to the unabashed Peeping Toms, is an object of unbridled lust . Thus the artist exploits the story, using it as an opportunity to paint a beautiful female body and a sexually charged scene. His Susanna recalls a pinup nude from a contemporary magazine, as opposed to Gentileschi’s innocent and anguished young woman.

An even more recent rendition of Susanna and the Elders (not included here) was that made by Archie Rand in 1992 as part of his acclaimed Sixty Paintings from the Bible series, which vividly updated the Hebrew Bible and Apocrypha’s archetypal stories in an expressionistic comic book style. It is remarkable how some features of the very varied works presented in this exhibition seem to have had a legacy in Rand’s provocatively contemporary take on the subject. Like the Lothair Crystal, Rand used both words and image to convey the narrative (though in expletive-ridden speech bubbles). Unlike Artemisia, he conveys no special sympathy with Susanna, but he shares a Renaissance fascination with the specifics of the dramatic events in the garden. And in common with Benton (though in his own more loosely painted style) he is bold in bringing Susanna into a present cultural moment.

The works of art in this exhibition were chosen as a means to upend most viewers’ expectations of Susanna and the Elders: a classicized figure subjected to the male gaze, bathing in a bounteous garden, and painted on canvas by a male master from the Renaissance or baroque period. The unknown maker of the Lothair Crystal, Gentileschi, and Benton (and later Archie Rand) subverted the norms of the canon in strikingly different and surprising ways. These artists add depth and complexity to an ancient parable meant to convey themes of piety and wise judgement but often, and unfortunately, codified by an engrained construction of gendered classicism that distorts the intended meaning of the apocryphal account.

References

Baskind, Samantha. 2016. Archie Rand: Sixty Paintings from the Bible (Cleveland: Galleries at CSU)

———. n.d. ‘Archie Rand: Sixty Paintings from the Bible’, and ‘Archie Rand: Sixty Paintings from the Bible (all 60 paintings in color)’, www.academia.edu

Commentaries by Samantha Baskind